Indefinite detention inevitably gives rise to the horrors recorded in the Nauru Files – the Department of Immigration has openly conceded as much in the past. That’s why Peter Dutton seeks to distract, in the same way his Liberal predecessors did before him, writes Max Chalmers.

At a certain point, after indulgent use, a rhetorical trick which once helped divert attention elsewhere becomes a spectacle of its own. It happened this week to Donald Trump.

Trump likes to push conspiracy theories against his enemies, often at moments when his own standing looks especially shaky. He has a particular way of doing it.

“You know, some people say that was not his birth certificate,” he said in 2013, after President Barack Obama released his birth certificate to prove he was an American citizen.

Some people say. Not Trump, necessarily. But some people. Who are they? Who knows, but apparently they’re saying it. Can it be verified? Not important, because now we’re talking about Obama’s family lineage instead of the fact the Republican nominee just declared war on Iceland and proposed allowing school aged children to be hunted for sport.

The would-be President uses a number of phrases similar to this one to great effect: they allow him to air an allegation without technically ever putting his own name to it. Some people are saying; many people are saying; I’m hearing.

The ‘some people say’ line was turned against Trump this week – but with the release of thousands of documents from Nauru as part of a Guardian Australia investigation into the offshore detention of refugees on the island, it still finds a good home in Australia.

The reports unearthed by the Guardian come from within the detention system itself, the testimony of asylum seekers and refugees, as well as those employed to guard and care for them. In handwritten notes staff record children inscribing death wishes in their homework and adults ingesting razors by enfolding them between pieces of bread. These sit alongside the now well-known accounts of sexual assault.

In response to the more than 2,000 incidents recorded – which range in severity from sexual assaults to minor disagreements – Immigration Minister Peter Dutton broadcast a set of the same vague insinuations his government habitually churns out when the horrors of detention are presented to the public. This is part of a cycle of public relations Australia has seen play out time and time again. It is a Coalition favourite, and remains an essential ingredient to the regime of offshore detention.

Without providing evidence, Dutton argued an unspecified number of the reports could not be trusted.

“Some people have even gone to the extent of self-harming and people have self-immolated in an effort to get to Australia. Certainly some have made false allegations,” Dutton said in a radio interview yesterday.

Some have made. Who exactly these people are, and how many among the scores of incidents of self-harm described in the Nauru Files Dutton believes are invented, are left unspecified. Behind Trump’s more bellicose delivery, it’s the vagueness that powers his slurs. The same goes for Dutton.

In a strikingly similar attack, Australian columnist and right-wing culture war hero Nick Cater criticised the Guardian for publishing the material.

Fighting these arguments is like boxing a ghost. There’s nothing to hit, no solid proposition to shake and hold down.

When Dutton made his remarks, was he talking about the 23-year-old Iranian who died as a result of his self-immolating in May? No, of course not. That would be a slur on a dead man that demands evidence. And that’s why Dutton didn’t say anything about Omid himself, who finally died on Australian soil as a result of his burns. In fact, he didn’t say anything about anybody.

This dog whistling both sustains and feeds off the idea that refugees are not trustworthy, a notion now extended to anyone who reports their trauma second hand. It is the very definition of prejudice, existing before evidence and plucking examples as it goes. Dutton doesn’t need to prove all the allegations are false, but if he can prove one is then it will taint all those other people – diverse as they are – who have contributed their testimony to these files.

“I have been made aware of some incidents that have been reported, [are] false allegations of sexual assault, because in the end people have paid money to people smugglers and they want to come to our country,” Dutton said earlier.

Even under Dutton’s reasoning, there must be hundreds if not thousands of incidents to be reckoned with. Shouldn’t he be a little more concerned by that? The Minister insisted he wouldn’t tolerate a single instance of sexual abuse, then cautioned people not to buy into the “hype” around the files.

This might be ghost boxing but it’s still a dangerous game, and one that is loaded in the Minister’s favour. If Dutton does have evidence to prove a single claim is false, the prejudice loop he taps into will cancel out accurate accounts of rape. There will be many in the Australian community who find it easy to believe that if one refugee is lying – or even simply mistaken – then all refugees are liars.

The danger of that incredulity is made clear when you compare Dutton’s talking point to the conclusions reached in an independent review into allegations of sexual assault on Nauru, delivered in early 2015 by former Integrity Commissioner Philip Moss. Allegations of sexual assault and witness testimony were found to be credible. Disturbingly, the following note was also attached:

“The Review concludes that there is a level of under-reporting by transferees of sexual and other assault.”

Under-reporting. That finding supports a statement issued by 26 former Save the Children staff in the wake of the Guardian leak, all of whom worked on Nauru. They authored many of the reports now publicly available.

“It appears from looking through the published database that nowhere near the full extent of the incident reports written on a day to day basis have been released,” Jane Willey, who served as a teacher on the island, noted.

“What you are seeing here is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Today, the Guardian has published evidence that Wilson Security regularly downgraded the the seriousness of reports.

Dutton implies the numbers presented by the Guardian are an exaggeration of fact. Moss says some of the most serious incidents don’t even make it into the books. The staff who wrote them say the Guardian’s cache doesn’t even represent the full record. Those on the ground are not pointing the same way as Dutton and Cater.

Below the surface of Dutton’s response is a history that gives us little confidence in his claims.

Today, it’s allegedly inventing claims of abuse to get to Australia. In 2001, it was throwing children overboard. And many years on from the SIEV 4, another Liberal Minister played the same game, pushing allegations to draw attention away from the dark side of detention. Again, they turned out to be thin.

Which brings us back to one of most Trumpian moment in recent Australian political history.

It was Scott Morrison who was forced to call the Moss review, bowing to pressure after months of media reports indicating sexual assaults on Nauru. Admitting such an inquiry is necessary is not what you’d call a good press, but the besieged member for Cook had a trick up his sleeve.

Calling what was then a rare press conference, Morrison said the allegations of “sexual misconduct” he was hearing were “abhorrent”. That wasn’t all.

“In addition to that, and in parallel, I’ve been provided with reports indicating that staff of service providers at the Nauru centre have been allegedly engaged in a broader campaign, with external advocates, to seek to cast doubt on the government’s border protection policies more generally, and that also casts some doubt on the integrity of previous allegations,” he said.

An article that morning in The Daily Telegraph had foreshadowed claims against welfare stuff in the centre, telegraphing the removal of 10 Save the Children staff members from the island. The Minister told journalists that staff in detention centres weren’t there to be political activists.

He said he had drawn no conclusions, then listed their wrongs. Alleged wrongs.

“The orchestration of protest activity and the facilitation of that protest activity on Nauru, including the tactical use of children in those protests, to frustrate the ability of those working in the centre to deal effectively and safely with those issues.”

“The coaching and encouragement of self-harm for people to be evacuated off the island and the fabrication of allegations as part of a campaign to seek to undermine operations and support for the offshore processing policy of the government.”

It was heavy stuff, and gave oxygen to the long promoted claim that advocates have encouraged refugees to hurt themselves. Yet when Moss delivered his final report four months later, he found no evidence to substantiate the claims Morrison had so boldly presented.

Skip forward to May 2016. The Department of Immigration has reached a confidential settlement with the Save the Children workers who were booted from the island, and Morrison appears on Barrie Cassidy’s Insiders to account for the mess he left behind (that’s Treasurer Morrison to you now, Cassidy).

How does he defend his actions? “I said allegedly, Barrie.”

Some people are saying. What I’m hearing. There are allegations.

On Cassidy’s show, Morrison refused to apologise to the Save the Children workers – the ones who allegedly, but in fact did not, coach self-harm. It was a performance that would have made Trump proud. How could you ever pin this on me, Morrison’s line went. All he had done was air the allegations to a room full of journalists he had himself assembled. Later evidence showed a key briefing Morrison appears to have relied on, and also seemingly behind the Daily Telegraph story, contained nothing even approaching hard evidence.

In fairness to Morrison, leaked transcripts from the Moss Review obtained by New Matilda indicate he genuinely believed Save the Children staff were out to get him. But there can be no doubt that airing what turned out to be unsupported allegations was also part of a smokescreen. The story shifted from one that would have been 100 per cent bad for the Minister, to one that was 50 per cent bad for him and 50 per cent bad for his opponents.

Dutton this week performed a virtually play-by-play re-enactment of that October 2014 press conference. The dopey inheritor of Morrison’s iron legacy, it may well be the case he simply does not possess the creativity required to weave unique spin without becoming entangled in a web of contradictions. Then again, perhaps he remembers how effective Morrison was when it came to shutting down criticism. By the time Morrison’s claims about the Save the Children staff were debunked, the October press conference was a distant memory.

Though Dutton’s re-enactment provides an insight into the Coalition’s consistent efforts to distract from the serious evidence of suffering in detention centres, it’s the Department of Immigration’s response that has been the most telling.

As the Minister delivered his script, the Department’s communications team put out an array of material. This included tweeting images of puppies.

Elsewhere, there was a press release. It was more honest than Morrison had been in 2014, and more stark than Dutton was this week.

Mimicking the Minister’s talking point on the verification of each individual report, the Department added their own stinging rebuke – that of a recalcitrant teenager caught in the act. Abuse in detention? Duh.

“The documents published today are evidence of the rigorous reporting procedures that are in place in the regional processing centre – procedures under which any alleged incident must be recorded, reported and where necessary investigated,” it said.

Incredibly, in a marvellously dextrous feat of logic, the Department claimed the overwhelming number of incidents demonstrated by these documents was a good thing. It proved they had done their job. The volume of problems reported, they argued, spoke in their favour.

That’s a sound argument only so long as you agree with the premise that the Australian government’s primary task is to count the number of times someone is harmed as a result of its policies, as opposed to preventing that outcome in the first place. You’ll also need to ignore Moss’s finding that underreporting is likely to be occurring.

And yet the release has a deeper and more disturbing message too.

You don’t need to tell us, Guardian and co. We already know.

Children are banging their heads against walls, and we know. Women are starving themselves while pregnant, and we know. People live in a despair that imprints itself on every part of their being; their dreams, their drawings, their disposition. We know.

That is the type of evidence contained in the Nauru Files Dutton hasn’t spoken to yet. The basic signs of trauma and psychological harm, the ones that have become the calling cards of Australia’s immigration detention network both on- and offshore. Allegations of sexual assault are a devastating escalation of that harm, but they’re not the underlying problem. They’re just one expression of it.

In his 7:30 interview last night, Dutton also briefly hit on the Department’s ‘we already know’ talking point.

It’s a tactic to shift the debate to more favourable ground. Details, we can squabble about – and some people are saying, I’m hearing, that some of the documents might not present truthful accounts.

But no one is seriously debating the fundamental truth that detention damages the people it touches. In less cryptic ways, the Department has long acknowledged this.

At one of Gillian Triggs’ early Children in Detention inquiry hearings in 2014, Department officials acknowledged the inverse relationship between the length of detention and a person’s mental health. Psychologists testified the same. More recently, the Department’s own top medical officer said plainly that detaining children is harmful to them.

“The scientific evidence is that detention affects the mental state of children: it’s deleterious,” Dr John Brayley told a Senate Inquiry.

“For that reason, wherever possible children should not be in detention.”

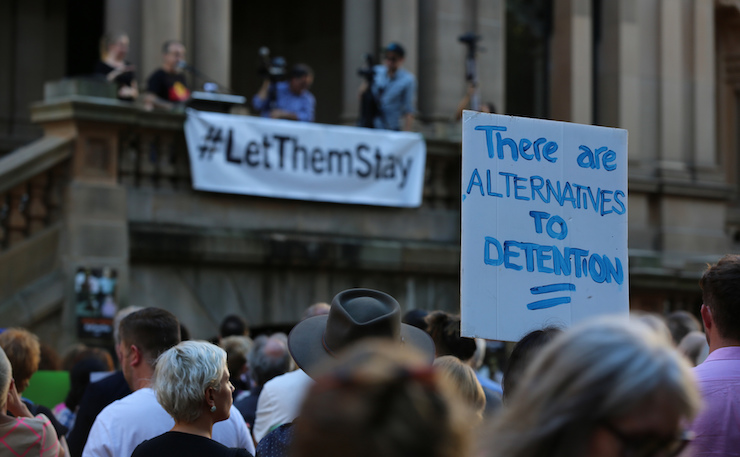

Refugees, asylum seekers, and those caught in Australia’s detention quagmire have spent the last decade and a half at times literally screaming this from rooftops.

RISE, a group founded by and for refugees, asylum seekers, and ex-detainees in Australia, made a succinct point as yet more ex-detention centre staff came out to denounce the system they had participated in. The organisation tweeted the following image.

The evidence of the harm to children is strong, but as groups like RISE are keen to remind people, it’s not just them.

Manus Island and the people who are supposed to be resettlement on Papua New Guinea have often received less attention than those on Nauru, despite ongoing fatalities. Kamil Hussain recently drowned on the island, his death following Hamid Kehazaei and Reza Barati, victims of violence and neglect. The Australian government refused to assist the repatriation of his remains to Pakistan. The first two casualties were direct consequences of detention. Onshore, the deaths have also continued.

While we must not sideline the mistreatment of these men, the Don Dale revelations have served as a reminder of the particular toxicity brewed when children and detention are mixed.

In startling evidence given to the Children in Detention inquiry in 2014, Dr Peter Young – who had been the head of Mental Health Services at IHMS, the company that provides healthcare in detention centres – said one third of children detained had experienced “significant mental health problems”. So damning were the results of IHMS’s mental health measures, the Department actually asked Dr Young to remove the figures from an IHMS report, in an apparent effort to cover them up.

It’s not hard to see why the Department would be nervous about independent measures of psychological health in detention falling into public hands. Earlier this year, after being given access to Australia’s Wickham Point centre, paediatric health expert Dr Hasantha Gunasekera found the results of a standard ‘at risk’ test for children were worse than any that that had ever been formally recorded.

There’s also reason to think that like psychological harm, abuse is an almost inevitable part of the detention experience for children.

Nell Bernstein, a journalist who has covered juvenile detention for a decade in the US, recently told ABC radio that the only way to stop scenes like those exposed in Don Dale is to get the children out of detention.

“I’ve been inside places that look like Ivy League colleges. And some or all of these things happen in all of them,” she said.

Vincent Schiraldi, a Harvard academic who previously advised the Mayor of New York and oversaw correctional facilities in that city as well as Washington D.C. said much the same.

Soon after taking over in D.C., it became apparent to him that guards were not only sexually abusing the prisoners. They were doing it to their colleagues as well.

“I think these institutions poison everyone they touch,” he said.

This is why Howard, Morrison, and Dutton prioritise distraction as a form of defence. You can pick around the sides, go ad hominem on Gillian Triggs, and tell the UN to stop lecturing you on torture. But at the end of the day, you’re not really arguing over the fundamental point.

We know that when you send people into detention you are doing them harm.

There’s a final contradiction in the responses outlined by both Dutton and the Department that tell us more than what their well-staffed communications teams had on their minds in the wake of the Nauru Files. It’s one that surfaces with every instance of abuse, and every time somebody tries to hold the Australian government accountable for their actions in a court of law. Dutton hinted at it on 7:30.

Asked why the government wouldn’t call a Royal Commission as it did after the revelations of abuse at Don Dale, Dutton pointed out that the island of Nauru is not in Australia.

The government, we are told, is obsessively monitoring every insinuation of an allegation of abuse on Nauru, while at the same time is out of the picture. We’re doing everything we can, but also, we have nothing to do with it. It’s out of our hands.

This is the paradox that underscores the defence of offshore detention, processing, and yet-to-be-seen settlement. If anyone truly believes the government’s excuses, they must be suffering severe cognitive dissonance.

Accountability is denied (some or many reports might not be true!) and owned (we know about all of them!) simultaneously. We employ the guards who practice the abuse, we count the number of times they abuse, we set up an inquiry when the abuse is too much. But when something that could actually undermine the foundations of that system like a Royal Commission we ask what’s any of this got to do with us?!

In the U.S., Donald Trump wants to build a wall. Thanks to the sea that girts this continent, a small fleet of turn-back boats, and two island camps with a well-documented history of abuse, Australia already has one.

It’s helped the government rundown onshore detention numbers, while packing terribly equipped camps overseas. As a result of legal challenges in Australia and Papua New Guinea, both those camps have been opened to varying degrees, extending the area of each person’s incarceration without actually ending it.

With pressure on the government from reporting like that which the Guardian has provided this week, as well as the much maligned human rights bodies and advocates who refuse to accept the status quo, small improvements have been made. They are patchy and inconsistent.

To the Department of Immigration, this is the system as it is intended to function. The reports are filed, categorised, and stored. The evidence piles up. The bipartisan support remains. Everything is in its right place.

When children have been brought over from these places and seen in the flesh, Australians have not been able to look away so easily.

But aside from those rare moments, and unlike Trump’s crumbling campaign, the efforts to distract are yet to seriously falter.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.