New Matilda columnist Dr Lissa Johnson wonders whether or not children should be removed from the Coalition’s care?

In March this year the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) launched a new recommendation that all doctors in the United States screen children for poverty.

The AAP introduced the measure because, “nearly half of young children in the United States [are]living in or near poverty, tied to a range of lasting medical harms”.

Nearly half? That can’t be right. The United States is the one of the world’s wealthiest nations.

Nevertheless, Associate Professor at Drexel University and Director of Community Pediatrics, Dr Daniel R Taylor says, “The most common – and serious – disease in American children is poverty.”

Poverty is known to cause various forms of irreversible damage to children, including low birth weight, infant mortality, impaired language development, chronic illness, nutritional deficits and injury.

An AAP policy document on the subject notes, “A growing body of research shows that child poverty is associated with neuroendocrine dysregulation that may alter brain function and may contribute to the development of chronic cardiovascular, immune, and psychiatric disorders.”

The document adds that, “child poverty also influences genomic function and brain development by exposure to toxic stress, a condition characterized by excessive or prolonged activation of the physiologic stress response systems.”

In others words, poverty is traumatic for children and toxic to their minds and bodies, causing “lifelong hardship”.

The latest census data analysed by The National Center for Children in Poverty at Columbia University reveals that 47 per cent of children under six years in the US, and 45 per cent of children aged 6 to 11 live ‘on or near’ the poverty line, defined as earnings of less than $48,016 for a family of four.

Twenty four per cent of children under 11 are doing it even tougher, living below the poverty line, on a family income of $24,008 or less.

In total this represents over 31 million kids.

Meanwhile America’s 20 richest billionaires enjoy as much wealth as all these children’s parents combined.

It’s terrible. But what has it got to do with Australia?

As others have observed, the Coalition Government’s ‘jobs and growth’ plan for re-election owes much to the economic policies of the United States. If we are to evaluate the Coalition’s plan, and see where it might lead us, the US is a logical place to look.

Thomas Fitzgerald, Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Notre Dame Australia, for instance, points out that, “In 2003 US President George W. Bush campaigned on a ‘10-year ‘economic plan’ for ‘jobs and growth’ by cutting taxes…. The rationale President Bush gave for those tax cuts needs little more than a nationality swap to stand in for Treasurer Scott Morrison.”

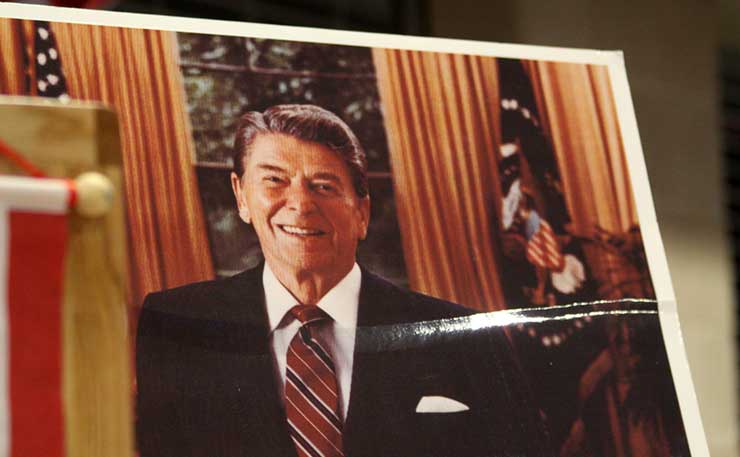

Going back further, Mike Seccombe of the Saturday Paper traces Turnbull and Morrison’s economic plan to Ronald Regan, who introduced the notion of growth through tax cuts to the US.

Seccombe notes that, “Following a sponsored visit by [former]Reagan adviser Arthur Laffer, Malcolm Turnbull’s budget is based on the fallacy of his trickle-down economics.”

Some call it Reganomics, some call it neoliberalism, some call it supply side or trickle-down economics, and some call it voodoo economics.

Most who have examined the evidence for it call it a failure.

Although economics is typically depicted as a numbers game hinging on budgets, deficits, surpluses, exchange rates and money, as a discipline it is considered a social science. Like psychology, economics involves the theory and study of human behavior. Economic behaviour in particular.

One difference between the two disciplines is that economic behaviour occurs en masse, at societal and international levels. As a result, it is difficult to simulate and study in a laboratory. The main tests of economic predictions take place in the real world.

To evaluate economic theories, economists study real-world data from real economies, finding patterns and relationships, drawing deductions, and reviewing economic models based on what they observe.

The United States, as one of the world’s largest economies, is a data treasure trove.

Professor of economics at UC Berkeley, Emmanuel Saez, long-time collaborator with French economist Thomas Picketty, has mined that trove, tracking measures of economic prosperity in the US from 1913 to the present.

Saez’s analyses have been influential in understanding the impact of the supply-side trickle-down economics introduced by Ronald Regan, and built upon ever since.

So what do his analyses tell us? Does Reganomics stimulate jobs and growth, as Morrison and Turnbull claim?

Certain kinds of growth, yes.

Stellar, spectacular, unprecedented growth in the wealth and income of the top one per cent of the population, as is increasingly well known. More modest growth in the wealth and income of the top 10 per cent. Stagnation and poverty for everyone else.

From 1993 to 2013, for instance, incomes of the bottom 99 per cent of the US population grew only by 7.3 per cent, while top one per cent incomes grew by 62.4 per cent.

Of the GDP growth that has taken place, not much has trickled down. The main beneficiaries have been the wealthiest at the top.

Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008, for instance, although the US economy has been recovering and growing, child poverty has been growing alongside it.

After 2008 the number of children living in low income families rose by 10 per cent. The number of children living on or below the poverty line rose by 18 per cent.

In the six years to 2015, “America’s wealth grew by 60 per cent… by over $30 trillion. In approximately the same time, the number of homeless children has also grown by 60 per cent”.

Is this the kind of ‘growth’ that Turnbull and Morrison have in mind?

The reason for this discrepancy, Saez’s analyses reveal, is that during the recovery from the GFC, 91per cent of the economic gains went to the top one per cent of the US population.

Nice growth if you are in the top one per cent. Not so nice if you are among the poorest 45-47 per cent of America’s children.

As Seccombe and Fitzgerald have summarised, “tax cuts did not encourage growth but did promote inequality”, along with “ballooning debt”.

Part of the problem is that the wealthy tend to hang on to their money. And send it offshore. They only spend around 30 per cent of it, unlike everyone else who spends most of what they earn. The other 70 per cent sits stagnant and unproductive.

But what about jobs? Have ‘flexible’ workforces and super-wealthy employers produced jobs, as Turnbull and Morrison predict?

Certain kinds of jobs, yes.

Low income jobs. Very low income jobs. Lots of them.

Fifty per cent of US working adults in 2013 made $27,851 or less per year.

As this article observes, “wages have stagnated since the Reagan era, even though productivity continues to increase. Corporate executives, in other words, are forcing workers to toil longer, harder and smarter than ever, but all the proceeds are going into the hands of the very rich.”

If this is what Morrison and Turnbull mean by ‘jobs’, then perhaps they understand the economic data better than they are letting on.

The stagnation in wages and low rates of pay for so many American adults is, of course, the rot at the core of the child poverty epidemic. Many parents simply can’t earn enough to support their kids.

Not for want of trying, however. Contrary to stereotype, nearly half of parents with children living in poverty in the US (48 per cent) have some college education.

Alongside the failures of the ‘trickle-down’ economy, another factor credited with causing poverty and low wages in the US is the weakening of unions.

Christopher Jencks, professor of social policy at Harvard, observes that “companies are more likely to choose the high road [decent wages and conditions]if there are unionized workers who can make abusing workers most costly”.

If low income jobs are the goal, no wonder the Coalition has been so hostile towards unions and workers’ rights.

But what is a psychologist doing talking about economic data, tax policy, wages, income and unions?

In psychological literatures policy areas such as these are considered ‘social determinants of health’. Social and economic policies have a significant, and often profound, impact on individuals’ mental health and wellbeing.

Political scientist Patrick Flavin and his colleagues, for instance, have found that labour market regulation (wages and conditions) exert a larger impact on individual wellbeing than a person’s marital status.

Similarly, reducing government spending on social services (healthcare and education) is associated with increased suicide rates in the US. Variations in government spending of as little as $45 per capita have been found to raise or lower suicide rates by 10 per cent.

User-pays healthcare kills as well. According to the National Coalition on Health Care, 1.5 million people in the US lose their homes every year due to medical expenses. Others opt to keep their houses but let their health fail.

Researchers at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health estimate that 875,000 US deaths in 2000 could be attributed to social factors related to poverty and income inequality, including unaffordable health care.

As Ian McAuley and John Pilger have observed, anger over these same kinds of hardships in the UK, under Thatcher’s trickle-down legacy, has played an important role in fuelling the BREXIT vote.

Say what they like at election time, the Coalition has been angling to cut funds to health and education, and shift costs to consumers, since their election in 2013. Abbott and Hockey went full throttle in this mission, which backfired and caused their venture to stall.

Turnbull and Morrison have been proceeding more slowly, but in the same direction, ever since. You can read analyses of their health and education policies here, here, here, here, and here.

The point for Australia’s children is that they need mentally and physically healthy parents in order to thrive. If past performance is any indicator, this is more likely under Labor than the Coalition.

As the following summary of a recent Fairfax-Lateral Economics Index of Australia’s Wellbeing notes, “Australians’ wellbeing grew 40 per cent faster each quarter under the past two Labor governments – equivalent to nearly $11 billion – on eight key indicators covering health, education and income distribution.”

Importantly, “Early childhood development improved under Labor but ‘fell backwards’ under the current [Abbott-Turnbull] government, due mostly to an increase in the proportion of children aged under five deemed to be developmentally vulnerable.”

Developmentally vulnerable. Already. And the Reganomics is just beginning.

With so many countries whose policies we could emulate, why the USA? On measures that matter most to the vast majority of Australians, the US falls repeatedly near the bottom of important international comparisons.

According to a recent UNICEF report, for example, child wellbeing in the US is among the lowest in the OECD. Only children in Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey and Israel suffer lower wellbeing than American kids.

Inequality and poverty follow similar patterns. The UNICEF report shows that only Turkey and Israel rival the US for income inequality. Meanwhile only Chile, Mexico, Turkey and Israel have larger percentages of their populations living in poverty.

Governments are aware of these policy-wellbeing relationships.

Just this month, researchers at Flinders University released a paper critiquing Australia’s policy record on social determinants of child health. They note that Australian children’s health and wellbeing are “middle of the road” relative to other OECD nations.

The authors explain that Australian governments have been provided with, “practical frameworks for translation of such evidence [on child health and wellbeing]into policy action”.

However, they note that policy action is frequently “not a priority” for governments, who “often took a narrow view of the evidence and drifted back to focus on the individual”. They cite as obstacles, “lack of commitment to social justice… and a lack of political will”.

The net result, they say, is an attitude of “victim blaming, placing the responsibility of raising a child in the hands of the mother alone”.

Ask any Aboriginal mother – or father – who has had their child removed. With over 50 per cent higher rates of child poverty, and double the rates of child mortality and developmental vulnerability compared to non-indigenous children, Aboriginal children and their families are in particular need of systemic solutions and care.

Rather than address the social determinants of these children’s hardship, however, the Abbott-Turnbull Government has choked and immobilised effective services, exacerbating rather than ameliorating harm to Aboriginal kids, while continuing to remove children from their families at ever increasing rates.

Were child protection a less individualistic, more policy-focussed and evidence-based affair, the Coalition’s competence to care for Australia’s children would be called into question this election time.

The Turnbull Government’s climate nihilism alone is grounds to take back our kids. Climate change impacts children more severely than adults, both now and in the future.

Equally concerning is the Coalition’s rejection of models for governance known to foster high child and family wellbeing, low child poverty, high social and economic equality, and strong economic growth.

Norway, Denmark and Sweden all fit this profile, ranking highly relative to other OECD nations on measures such as child wellbeing, and low on measures such as child poverty and inequality. They also boast among the strongest economic growth in the OECD, significantly above that of the United States.

As Ian McAuley and Miriam Lyons outline in their book Governomics, the Nordic nations have achieved their prosperity through progressive taxation and well-funded public services.

If jobs and growth are what it’s all about, why not emulate these countries?

That’s what the OECD recommends.

The OECD has launched an initiative called In it Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. The summary on the OECD website says that income inequality, “tends to drag down GDP growth, due to the rising distance of the lower 40 per cent from the rest of society. Lower income people have been prevented from realising their human capital potential, which is bad for the economy as a whole”.

As a result, the OECD recommends achieving economic growth through “policy packages” that feature “redistribution” and “progressive” tax. They advise that, “Policies need to ensure that wealthier individuals but also multinational firms pay their share of the tax burden.”

In other words, the opposite of what Turnbull and Morrison are doing.

The OECD describes itself as having a “commitment to market economies backed by democratic institutions”. Not exactly heterodox or fringe.

The OECD’s mission is to “set international standards on a wide range of things, from agriculture and tax to the safety of chemicals”.

So why would the Coalition fly in the face of OECD recommendations? Only to follow the out-dated advice of an ex-Regan advisor whose ideas have been widely discredited?

Why adopt policies known to cause unnecessary poverty and hardship, including lasting and devastating harm to kids, when other alternatives exist?

More equal alternatives. With less extremes of wealth.

Hang on.

Less extremes of wealth…

Could that be…?

No.

The one tantalising prize that sets America apart. The right to be a squillionnaire.

Surely not.

I mean there’s elitism and then there’s…

We’re talking child poverty here. Who puts obscene wealth ahead of children’s welfare?

It’s a question worth asking on election day.

Who indeed?

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.