Skulking around underwater in wildly overpriced (and thus far imaginary) submarines is unlikely to persuade China to ‘be reasonable and see things our way’. Defence experts Mark Beeson and Vince Scappatura weigh in on the ongoing AUKUS debacle, and the latest ‘Chicken-Little-sky-is-falling-in’ editorial crusade from the Murdoch press.

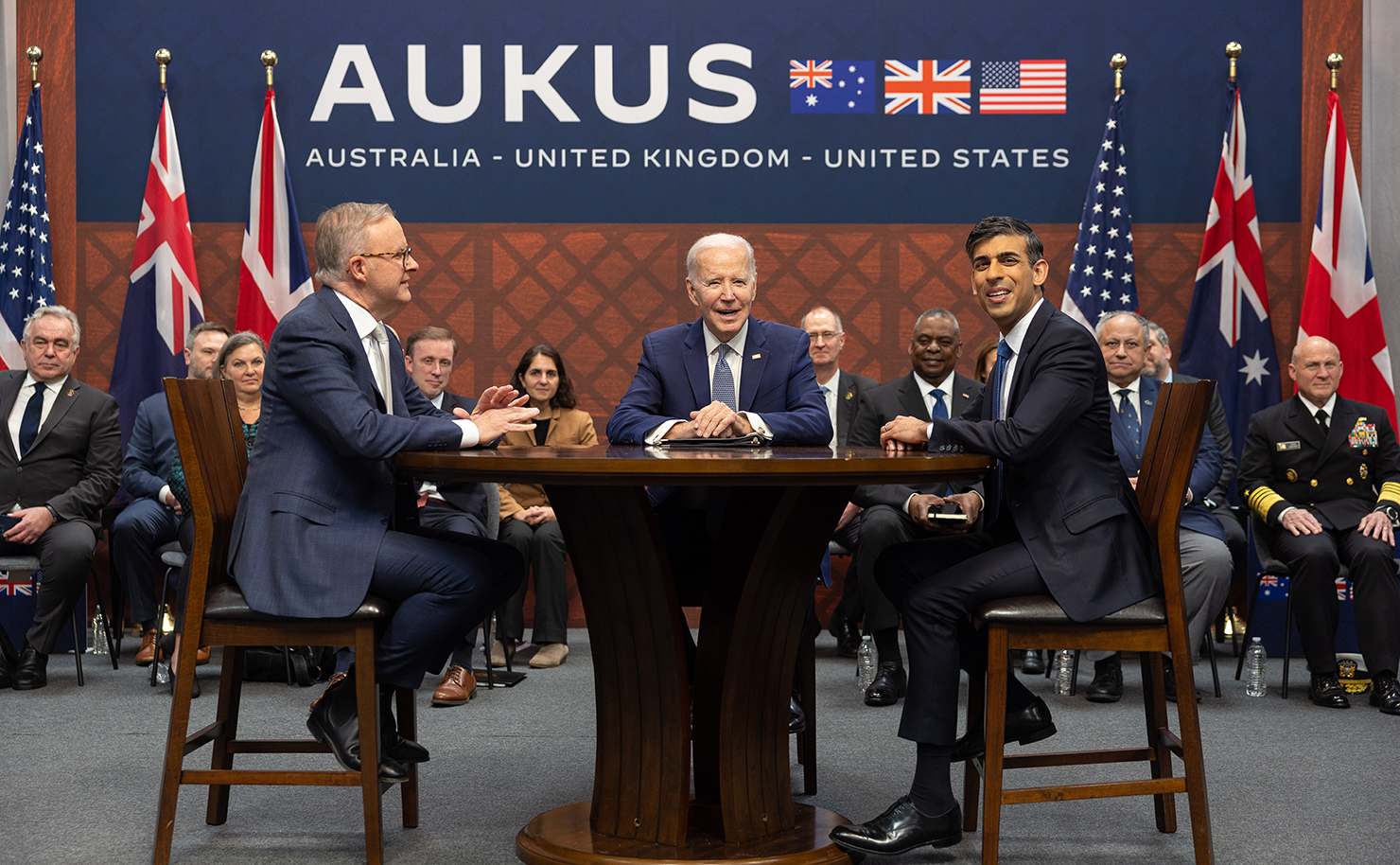

The Albanese government has committed Australia to the most expensive defence procurement in the country’s history. They are being offered enthusiastic support in this by the Coalition; unsurprising given that the purchase of nuclear-powered submarines and the creation of the AUKUS alliance were largely the Morrison government’s initiatives.

This rare outbreak of bipartisanship and policy agreement is not universally shared, however; not that you would know it if you’re unfortunate enough to get your news exclusively from the Murdoch press. As with its view of climate change, there is a consistent editorial line on AUKUS and ‘critical’ voices are rarely even referred to, let alone heard.

We have personal experience of this having signed an open letter, along with over 100 other academics with expertise in defence and foreign policy, questioning the underlying strategic rationale of both AUKUS and the acquisition of submarines that will cost at least $368 billion, if and when they are ever delivered.

Paul Monk, the self-styled ‘most versatile public intellectual in Australia in our time’ [Ed’s note: That is literally the claim Monk makes about himself on his own website… while wearing a French beret and a high-neck sweater], was given a platform by The Australian to put us in our place. Needless to say, we haven’t been offered the right of reply.

Monk’s central argument, like that of the Albanese government, is that we need the alliance to “deter Beijing’s escalating militarism”. In this context, “the system of collective security put in place by the US after 1945 has served Asia exceptionally well,” Monk claims, as do the policymaking establishments of the US and Australia, of course.

Yet even if we ignore the conflicts in Korea, Vietnam and Afghanistan, it’s plain that the overwhelming military superiority of the United States – with or without its allies – has conspicuously not ‘deterred’ China from reassuming what its leaders see as its rightful place at the centre of regional affairs.

In such circumstances, there is absolutely nothing Australia can do to change this underlying geopolitical reality: if China is not deterred by the US’ gargantuan ‘force projection’, its policy settings will not be recalibrated by Australia, no matter how many subs we eventually acquire. Indeed, the only influence Australia can realistically expect to exert is by educating Chinese students and engaging the PRC’s leaders through trade and diplomacy.

Consequently, there are serious, so far unaddressed, questions to be asked about the underlying assumptions that supposedly justify this hugely consequential decision, as well as the enormous opportunity costs that will directly impact Australians in the meantime; most of which will fall upon the heads of the youngest members of society who are increasingly despairing of enlightened leadership that will secure their future.

It is not necessary to rehearse all the problems currently afflicting the younger generation to recognise that climate change is coming to get them in a way the Chinese simply aren’t. One thing we can all agree on is that China is not planning to invade Australia. As a result, we actually have the chance to think more imaginatively about what it actually means to be secure, simply as a consequence of our benign geography.

True, there are some loathsome regimes around the world, and there is much about Xi Jinping’s version of Chinese civilisation that is disappointing and alarming. But buying expensive submarines is not going to change that; only the Chinese people can do that. Suggesting that China is ‘comparable to Nazi Germany’, as Monk does, is not helpful nor accurate and will only give impetus to nationalist and anti-Western sentiment in China.

Indeed, it’s worth remembering that the arms race and the alliance networks that existed in Europe before World War I, which were widely expected to keep the peace, directly contributed to the mind-numbing extent of the pointless slaughter that followed. Ironically, successive generations of young Australians have been encouraged to believe that the ‘sacrifice’ of tens of thousands of their historical counterparts was vital to protecting our freedom. This socialisation process is being expanded to persuade schoolchildren about the merits of AUKUS.

It’s easy to be wise after the event, no doubt. But it’s not necessary to be blind to possible strategic outcomes or even imaginative alternatives before blundering into yet another avoidable cataclysm, especially when it has the potential to go nuclear.

This is why more inclusive debates about the consequences of truly monumental policy decisions is essential. True, it is unlikely we will all agree. The 100 signatories of the open letter don’t agree on everything, but they do recognise that unless we have such a debate the chances of making even more appalling unforced errors, like the decision to take part in the Iraq war, for example, cannot be ruled out.

Significantly, it is not only concerned academics who are mobilising in opposition to the submarine project at a time of national stringency. Trade unions, civil society activists and even other, more critically minded public intellectuals, are demanding greater accountability and justification from our leaders. That is, after all, what makes our democratic system so much better and more inclusive than China’s, isn’t it?

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.