The uprising in Kalgoorlie was a cry for reform of a failing justice system, writes Michael Brull.

Some readers have responded sceptically to Chris Graham’s analysis of the Kalgoorlie uprising, and the many injustices Aboriginal people have faced in the criminal justice system. In theory, some of their reservations have some validity.

It is true that there is little evidence on the public record explaining the circumstances in which the 55-year-old man killed the 14-year-old Aboriginal boy. For those of us who don’t know what actually happened, it is possible that manslaughter really does fit the facts.

Those sceptics can point out with total justice that people are entitled to a presumption of innocence until they are proven guilty. It is better to have a criminal justice system that errs on the side of caution, rather than unjustly imprisoning an innocent person.

If someone is believed to have done something wrong, those charges should be tested in a court of law.

The sceptics might say that whilst Aboriginal people in Kalgoorlie are fully entitled to their anger, the courts should act on the basis of due process, not public outrage.

What is striking about each of those arguments is that they could all be applied by Aboriginal people. Each of those fundamental principles has been openly flouted for years by the criminal justice system in relation to Aboriginal people.

Take Kalgoorlie, the town of the uprising. Several years ago, a 23-year-old woman allegedly crashed a stolen car whilst intoxicated. Though she didn’t harm anyone, she was given zero due process. She was locked up without trial. Her imprisonment lasted for almost two years.

The woman in question, Rosie Ann Fulton, was born with foetal alcohol syndrome. The Kalgoorlie Court found that she was unfit to stand trial. So they locked her up. She was never give a presumption of innocence, and her detention was never subjected to judicial oversight.

Rosie Ann is Aboriginal, and she is no anomaly. Western Australia’s Inspector of Custodial Services Neil Morgan conceded that, “The vast majority of people who’ve been caught under the Act and held under a custody order by reason of a cognitive impairment are in fact Aboriginal people, and a large number of them are Aboriginal men and women from remote and regional Western Australia.”

The Act in question is the Criminal Law (Mentally Impaired Accused) Act 1996. It provides that if the court finds someone has committed an offence from a specified list, and has been found unfit to stand trial, then they must be subject to a custody order.

In their 2012 landmark report No End in Sight, the Aboriginal Disability Justice Campaign (ADJC) documented the problem of the imprisonment and indefinite detention of Aboriginal Australians with cognitive impairments in Australia.

They observed that, “In Western Australia (WA) and the Northern Territory (NT) this detention occurs in prison (generally in maximum-security settings) and in Queensland and Tasmania, this detention occurs in psychiatric hospitals.”

The ADJC estimated that there were nine people indefinitely detained in the NT, and all were Aboriginal.

In Queensland and Tasmania, they were unable to ascertain who was being detained.

In 2014, the ADJC found that there were 30 Aboriginal people indefinitely detained without trial. It could be more, but the governments have not provided statistics.

One famous case is that of Marlon Noble. Another Aboriginal person from Western Australia, Marlon was accused of sexually assaulting two children. He was found unfit to stand trial, and thus imprisoned indefinitely.

As there was no trial, and no judicial oversight of his detention, it didn’t matter that he was innocent, and that the alleged victims and their mother later publicly denied the charges and urged Marlon’s release. He was imprisoned for 10 years, before finally being released, subject to a range of draconian conditions.

Another case came to public attention in 2014, the story of “Jason”. Jason is an Aboriginal man with a mental impairment, living in Western Australia. In 2003, aged 14, he stole a car with a group of other children. As police chased him, he crashed the car. His 12-year-old cousin died in the crash. According to the ABC, “He has an intellectual disability and was left brain damaged from substance abuse.”

The court found him unfit to stand trial. He too was jailed indefinitely under the Criminal Law (Mentally Impaired Accused) Act 1996.

I interviewed his advocate a few weeks ago, Taryn Harvey. She regarded the case of Jason as the “most unfair” application of the laws of which she was aware.

According to Harvey, Jason has “never had any support to deal with trauma associated with that accident.” Though he was only 14 at the time of the crash, he has been under the Act for 13 years. He has spent about 12 of those years in prison, including periodic leaves of absence as the years went on. In the last year, his periodic detention has shifted to a newly built “declared place”.

For the 20 years the Act has existed, Mentally Impaired Accused Boards didn’t have to detain people in prisons. The Act also provided for detention in an authorised hospital, or a “declared place”.

Theoretically, the Western Australian government could have just sent Aboriginal people unfit to stand trial to declared places, where they could be rehabilitated as appropriate and treated humanely. Harvey explained that for 19 years of the act, no relevant declared place existed, as “no-one bothered to build one. Everyone was happy for people to go to jail.”

Harvey explained that if Jason had stood trial, he would have faced a sentence of three to seven years. Instead, he has been spent most of 12 years in prison. Harvey says the impact of all those years of incarceration on Jason has been “heartbreaking”. There has been zero judicial oversight of Jason’s many years of detention, or his continued subjection to the Mentally Impaired Accused Board.

The Western Australian Association for Mental Health has issued a brief report on five obvious reforms to address the draconian and unjust laws that impose indefinite detention on people with mental disabilities in WA.

The reforms are all obvious, and would provide basic norms of due process, natural justice and judicial oversight. The fact they have not been implemented shows how happy people in WA are to suspend fundamental principles of the rule of law, in relation to some of the state’s most vulnerable people.

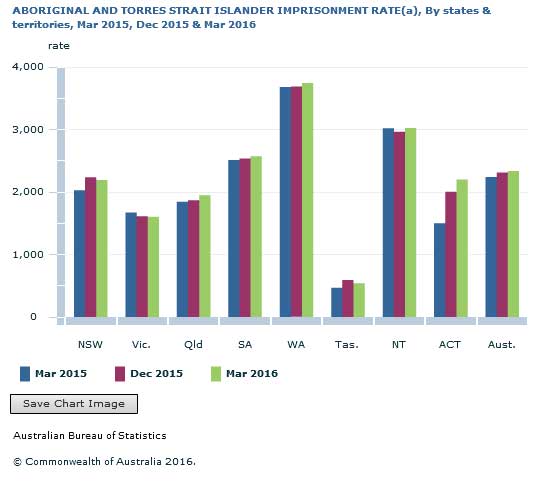

This is what rankles so deeply about the man who ran over Elijah Doughty. Western Australia is not a place where the criminal justice system prizes leniency and the presumption of innocence. It is the second most punitive state or territory in Australia. Behind only the Northern Territory, it imprisons just shy of 300 people per 100,000 adult population.

That punitive approach is particularly targeted at Aboriginal people. Western Australia has the highest rate of Aboriginal imprisonment in Australia, at a rate of 3,745 per 100,000.

Though Aboriginal people make up only 3 per cent of the population of WA, Hilde Tubex observes that they make up 40 per cent of its prison population. They are over-represented by a factor of 15.6. The situation is even worse for Aboriginal children in WA.

Amnesty International reported that they are 53 times more likely to be jailed than non-Indigenous children.

It is understood in economics that poverty is a measure of relative wealth, not an absolute one. Poverty isn’t a matter of how much you have, but how it compares to others in the society you live in.

In that sense, justice is similar. If you’re an Aboriginal person in WA – or in Australia for that matter – you can’t help but notice how much justice there is for white people, and how much injustice there is for black people.

Whilst white people overwhelmingly get the benefit of the doubt and a presumption of innocence, Aboriginal people are particularly likely to be denied those basic principles.

The riot in Kalgoorlie didn’t target cop cars and a courthouse as demonstrations of irrational mob violence. They were manifestations of long-standing, legitimate grievances.

When those grievances are addressed, Aboriginal people won’t have reason to look with disgust at the criminal justice system.

Heavy-handed policing might prevent more outbreaks of violence in the short-term, but systemic change is the only way to prevent more riots in the long-term.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.