The murder of nurse Gayle Woodford in the remote community of Fregon, in the APY Lands in South Australia, is an horrendous tragedy.

I’ve been watching the story unfold for days, hoping Ms Woodford would be found alive. Late yesterday, however, police discovered her body in a shallow grave, about 1.5 kms from the town.

A 36-year-old man was today charged with her murder, after earlier being charged with the theft of the Nganampa Health Council ambulance.

The grief felt by Ms Woodford’s family and friends is unimaginable. She was a woman who clearly devoted her life to helping others, and in particular some of the poorest and most marginalised people in this nation.

Similarly, there is a deep sense of grief and loss not just in the Fregon community, but across the vast APY Lands, a region that knows more than most about pain and loss.

When a person – white or black – dies in tragic circumstances in an Aboriginal community, the community itself feels a collective sense of responsibility. That’s the way it has always been, and the circumstances of the tragedy are irrelevant.

When a tourist falls from Uluru and dies, for example, the local Traditional Owners feel that death acutely, and hold themselves personally responsible. That’s one of the key reasons they’ve long wanted to close down the tourist climb. But when a woman like Gayle Woodford is murdered, that sense of grief is compounded by a deep sense of collective shame.

Understanding this is key to also understanding why some of the media reporting – and social media commentary – around the death of Ms Woodford is so harmful, and so wrong.

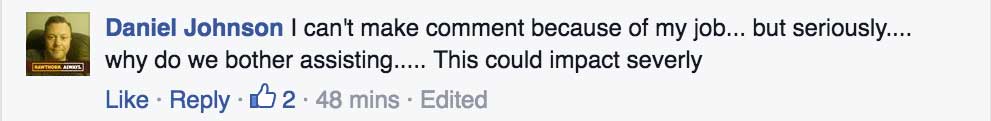

When the news of Ms Woodford’s death was confirmed, I braced myself for what I thought would be the inevitable onslaught of mainstream and social media rage, an anger that would seek to highlight race as the factor in Ms Woodford’s death.

It’s worth acknowledging that in large part, that onslaught has not occurred. Most media have reported the matter responsibly. Most social media commenters have focused on the crime, and the individual.

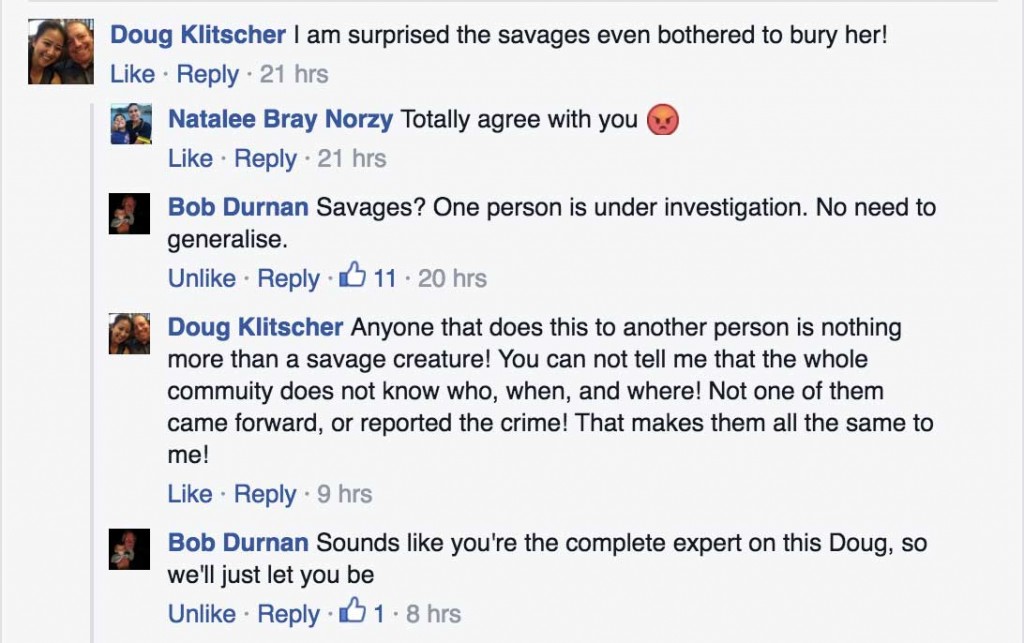

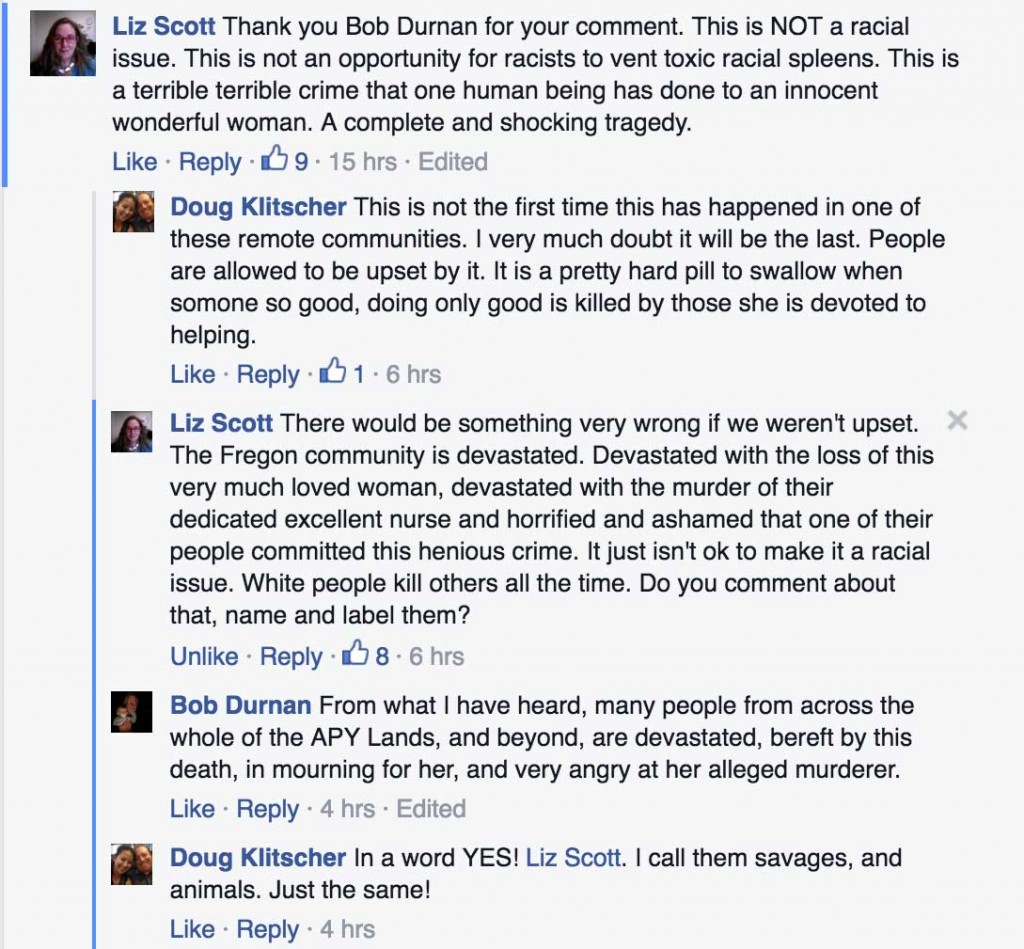

But there have been incidents of media and individuals seeking to explain the tragic death of Ms Woodford through the prism of race, and as more details emerge, that’s likely to intensify. Ms Woodford died, they surmise, because she worked in an Aboriginal community. And Aboriginal people are all the same.

In mainstream media, the Adelaide Advertiser has led the charge in trying to make the race of the alleged offender relevant, working ‘Aboriginal’ into its copy whenever possible. The alleged offender, from an “Aboriginal community”, picked up “Aboriginal people” and transported them in the stolen ambulance.

By contrast, the ABC has reported extensively on the death, but the facts its found relevant are that Ms Woodford died in a “remote community”. The man charged is simply “aged 36”. The people found in the ambulance with him were simply that – people. If you search the story for the word ‘Aboriginal’, it doesn’t appear once. And that’s because race is utterly irrelevant.

Ms Woodford wasn’t harmed by the Aboriginal community she served. She was murdered, allegedly, by one man, acting alone.

When Adrian Bayley murdered Jill Meagher in September 2012, the race of the perpetrator, let alone the community in which it occurred, was never considered a factor. There was, however, an important discussion around male violence against women, and that context should be part of community discussion around the death of Gayle Woodford, because it is one of only two relevant ‘facts’ in this story which help explain such a senseless death.

The murders of women are overwhelmingly committed by men. It is an undeniable, inescapable fact. And like collective grief in Aboriginal communities, that’s the way it has always been.

The other fact that is relevant in the death of Gayle Woodford is that she often worked alone, as do hundreds of Remote Area Nurses (RANs) across the country, every single day. This is in no small way because of the entrenched and historical under-investment in Aboriginal communities.

Context here is important – the killing of a nurse, particularly in a regional or remote community – is extremely rare. I’ll stand corrected, but the most recent example I can find of a nurse murdered while on duty was in 2011. It occurred in Orange, NSW and, although race is irrelevant, the offender was white.

At the time, The Australian reported: “NSW Nurses Association assistant general secretary Judith Kiejda said the union was continually working to improve safety in the workplace, and this was ‘a very rare’ incident.”

The Australian noted it was the first killing of a nurse on duty in NSW since 1994, when Sandra Hoare was raped and murdered in Walgett, a town in the north west.

That murder was perpetrated by two Aboriginal men – cousins Brendan and Vester Fernando – who saw Ms Hoare working alone in the local hospital. New Matilda wrote about this murder only last week, highlighting the breathtakingly racist attempt by author and shock jock Paul B. Kidd to ascribe the behaviour of the Fernando’s to an entire Aboriginal race.

Of course, none of this is to suggest that nursing is not an inherently dangerous profession. It most certainly is.

The comments in a petition circulating online tonight, calling for increased resources for nurses working in regional and remote regions in response to the murder of Ms Woodford, include compelling anecdotes of RANs working in conditions in which they routinely fear for their safety.

These messages cannot be ignored, because they accord with what we already know, and have long known – all nurses will be the victims of abuse and violence in the course of their career.

A report in the Brisbane Times in December last year noted that every week, 17 workers – mostly nurses – are assaulted at Queensland Hospitals. In remote communities, there’s also an inherent danger. In 2012, for instance, nurses were flown in and out of Kalumburu, after rising local tensions. Other health professionals, such as domestic violence workers, and emergency personnel, face similar risks.

In 2008, a nurse was raped in the Torres Straits while she slept in her accommodation. It followed a report ignored by the Queensland Government almost two years earlier which warned that the staff sleeping quarters lacked basic security.

Nursing is a profession that brings with it substantial risk, and yet nurses confront these risks regardless. That’s a large part of why the death of Ms Woodford hurts so much. These people – overwhelmingly women – seek to ‘do no harm’ often at the risk of their own personal safety.

Clearly, a community discussion around the safety of nurses is warranted. The practice of RANs working ‘one-up’ anywhere – from Fregon to Brisbane – needs review.

Many remote Aboriginal health organisations already have a policy of ‘two-up’ nursing, although in practice it’s common for RAN’s to open their doors in the middle of the night, alone, to complete strangers seeking help.

But a salient point in any public discussion about the risks of nursing is that it is inherently dangerous no matter where you practice it. My mother, a retired nurse who ran an emergency department near Kings Cross can tell you that dealing with a drunk from the city streets is no less dangerous than dealing with a drunk from a remote Aboriginal community.

That’s part of nursing, and nurses embrace this reality with their eyes wide open.

So the most pressing need – the best way to reduce violence against the women and men who serve our communities – is greater discussion around male violence.

We’ll never eliminate it entirely, but the memory of Gayle Woodford can be honoured by tackling this issue with honesty and resolve, and by more Australian men standing up and accepting collective responsibility. Just like Aboriginal communities have been doing for thousands of years.

A fundraising page has been set up here to assist the Woodford family.

* New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. If you appreciated this story, please consider supporting us with a subscription – click here, they start from just $6 per month.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.