In the first real policy of the election campaign, Labor has doubled down on education. Will anyone notice, asks Ben Eltham.

The Australian Labor Party announced a rather significant policy last week.

Entitled “Your Child, Our Future”, Labor’s new schools plan builds on some detailed work the party has been doing in opposition.

Labor committed to “fully funding” the final two years of Julia Gillard’s Gonski schools funding reforms, in other words out to 2019. Funding for the policy had been left in limbo by the Coalition government, and is not expected to be renewed.

Lest we need to remind you, the Gonski reforms, named after the review of schools policy by merchant banker David Gonski, are about distributing far more funding to disadvantaged schools in poorer suburbs and regions. The thrust of the policy is to reduce yawning inequality in Australia’s school system. They are expensive, and have been major battleground of federal politics since the Gonski Review was handed down.

The Gonski reforms have definitely made a difference so far, particularly to public primary schools. Where the extra money has flowed, it has alleviated pressure on hard-pressed state schools and allowed school principals to invest in better resources for students that need them. Labor argues that the end of Gonski funding next financial year will strip around $3.2 million away from the average public school.

On the other hand, the Gonski report was itself the product of a deeply-flawed policy process, in which Gonski and his review panel were instructed to come up with a plan that made no school worse off. This locked in vast public subsidies for wealthy private schools and the Catholic system that could have been better spent on lifting Australia’s falling educational standards.

Mind you, things have definitely got worse under the Coalition. Since its election in 2013, the current government has attacked public funding for education at almost every opportunity. One of the Abbott government’s very first broken promises was to abandon support for the Gonski reforms in late 2013. Some commentators date it as the beginning of Tony Abbott’s downward slide in opinion poll ratings.

Universities policy under Christopher Pyne was also a debacle, in which the entire university sector was held hostage to a fee deregulation policy that failed to pass the Senate.

Now Labor has fired the first shot of the election year with a robust, costed and detailed education policy.

The only problem? No-one seems to have noticed.

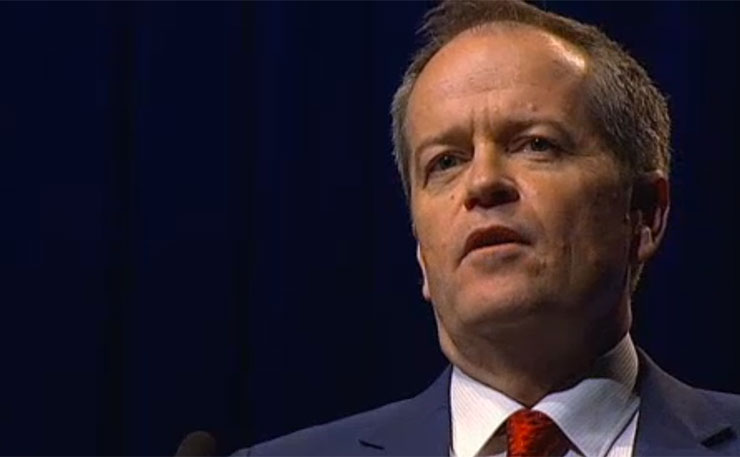

After a ripple of media coverage late last week, Labor’s schools plan seems to have sunk without trace. Maybe it was bad timing, or the policy’s terrible name. Maybe other events just overwhelmed the policy launch. Or maybe it was the abysmal popularity of Labor leader Bill Shorten.

Media coverage has instead turned to the Coalition’s increasingly clear intention to raise the rate of the GST to 15 per cent. This is undoubtedly tempting ground for Labor to fight on – the party has already signalled it will ramp up for a full-scale anti-GST campaign (despite the fate of Kim Beazley in 1998, when a GST scare campaign wasn’t enough to get an unlucky ALP over the line).

Labor has long sought to “own” education as one of the key planks of its re-election platform. Last year, the party committed to substantial extra funding for universities, tied to increasing enrolment for disadvantaged students and raising the number of graduates from science disciplines.

As Melbourne University’s Glenn Savage notes, “breathing new life into the Gonski debate … offers Shorten a rare chance to distinguish Labor from the Coalition on education and draw what is left from the cup of history that has solidified Labor as the education party among many Australian voters.”

The Gonski announcement commits Labor to a headline figure of $37 billion, though the true figure is a lot less than this because much of the money is already in the budget forward estimates. It would be better to use the near-term promise of $4.5 billion, while recognising that Labor has also promised to lock in extra schools funding for the decade out to 2025-26 – a full three federal elections away.

Labor has certainly done some homework. The new policy comes with ambitious metrics that the party plans to meet, including a year 12 graduation rate of 95 per cent. More science teachers will also be trained and employed. There will be more resources for students in schools, and more help for students with a disability.

And Labor has costed its policy, too. The ALP claims it will fund the promise via a range of revenue measures announced last year, such as tightening superannuation tax concessions and cracking down on multinationals avoiding their fair share of tax. On the other hand, this also means that Labor has just spent most of the hypothetical “savings” it has identified after more than a year of painstaking work in opposition.

This reminds us that Labor needs to fight the coming election on economic competence every bit as fiercely as on social policy. And while voters prefer it on health and education, they still prefer the Coalition on the economy. That may not be fair – the Coalition has actually spent more and borrowed more than Labor did in office – but it remains an electoral truth that the ALP must confront.

It’s a problem for Labor – a warning sign, even – that, on early signs, last week’s education announcement has yet to cut through. Perhaps education will build as a sleeper issue, but the history of the schools policy debate in this country suggests that Labor will struggle.

Disadvantaged schools are the ones that need extra public funding the most. But they are also the part of the education sector with the softest voice and the least lobbying clout. In contrast, the Catholic and private schools exert a muscular influence on the education policy environment. They are only too happy with the current arrangements.

Labor has done the right thing in backing extra Gonski funding, but it will need to campaign hard in the community right up until election day if is to turn education into a ballot box winner.

And can Bill Shorten really lead a successful campaign? That’s a question few in the ALP want to face right now. But Shorten’s unpopularity is a problem that can’t be wished away.

Sooner or later, Labor is going to have to confront the thorny dilemma of what to do about Bill.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.