Election night was a disaster for the Liberals, and for the Prime Minister in particular. Ben Eltham breaks it down.

It must have been a grim night for the Turnbulls in Point Piper.

The Prime Minister elected not to join the Liberal Party function at the Sofitel Wentworth for initial counting. Instead he and Lucy Turnbull stayed home at the mansion, ensconced in considerable comfort while the train wreck of his election campaign piled up across the marginal seats of middle Australia.

As the voting results flowed in from around the country, it was immediately clear that a swing was on. And it was a considerable swing: 3.3 per cent nationally, in two-party preferred terms.

Not for the first time, the pre-election polls were basically correct: with Labor polling at or very close to 50 per cent, the Coalition would come perilously close to losing government.

One by one, and then in twos and threes, the Liberal seats fell. They fell in southern Queensland, in western Sydney, in Tasmania and in the west.

In Queensland, big swings in Longman and Flynn accounted for rising star Wyatt Roy and time-server Ken O’Dowd. In New South Wales, the Coalition conceded the western Sydney trio of Lindsay, Macarthur and Macquarie. The Liberal Party also lost in the central coast seat of Dobell, and Labor’s Mike Kelly won back his former seat in the perennial bellwether of Eden-Monaro.

Tasmania was a Coalition wipe-out: the entire state is now Labor or independent, with Liberal hardliner Andrew Nikolic a notable casualty in Bass. In South Australia, the Nick Xenophon Team claimed Mayo from the disgraced former cabinet minister Jamie Briggs, and is still threatening in Grey. In Western Australia, Labor claimed the new seat of Burt in outer Perth, and is pushing hard to win Cowan.

Victoria had been hopeful for the Coalition, but even there the government could make little headway against a dominant Labor, holding its existing seats but winning at most one seat extra, depending on the neck-and-race in Chisholm.

All told, the Coalition has lost at least 12 seats. That takes it to the threshold of minority. On the current count, the Coalition holds between 69 and 73 seats, with between 11 and 14 seats still in doubt. A hung Parliament, in which neither major party can govern in its own right, remains the most likely outcome.

As the night wore on, the Coalition always seemed within reach of victory. But it never fell over the line. As seats swayed dramatically back and forth, it became clear that this would be a very close contest: the counting in Chisholm, for instance, finished for the night with Labor and Liberal candidates separated by just 25 votes. In the lengthening evening, both Bill Shorten and Malcolm Turnbull delayed their speeches. And delayed them. And delayed them.

By 11 o’clock, when Shorten decided to speak to his supporters at Melbourne’s Moonee Valley Race Club, it was clear that the election result would not be decided on the night.

Shorten seized the occasion, delivering a victory speech that began with the triumphal declaration that “Labor is back”. He went on to stake out Labor’s domain as the party for middle Australia, claiming the result as a vindication of Labor’s policy platform, and its determination to “save Medicare.” Shorten was measured, confident and even prime ministerial, promising to work hard for supporters whether in government or in opposition, and dedicating the night’s gains to his wife Chloe and to the “mighty trade union movement”.

The contrast to events unfolding in Sydney could not have been starker. The Coalition, perhaps believing that a little more time would deliver that decisive 76th seat, held on for victory. So Turnbull waited at Point Piper. And waited. And waited.

By the time Turnbull eventually appeared at the Sofitel, it was well past midnight.

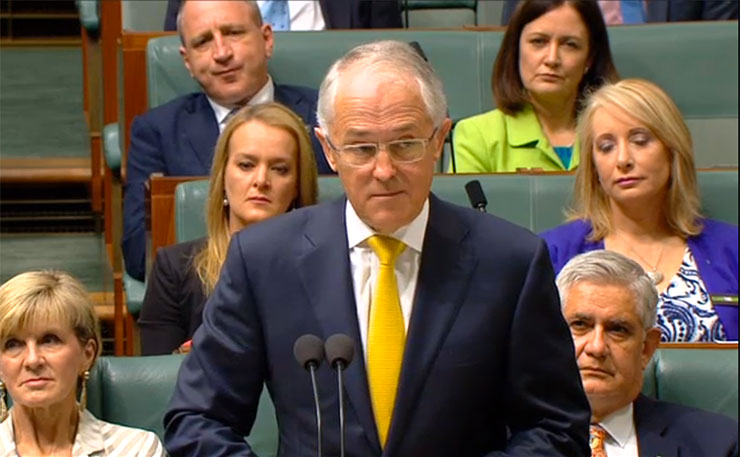

“We have every confidence that we can form a Coalition majority government,” Turnbull said at least three times in a rambling and angry speech that dismayed even friendly commentators and supporters.

The Prime Minister was irritable and unfocused, mumbling about pre-poll votes and railing against Labor for what he called its lies about Medicare. Despite the lateness of the hour and gravity of the moment, Turnbull wasted much time complaining about ‘Save Medicare’ text messages sent to voters, even suggesting he would refer the matter to the police.

“The Labor Party ran some of the most systematic, well-funded lies ever peddled in Australian politics,” Turnbull shouted. Strident, ragged and splenetic, it was the very opposite of Shorten’s composed speech.

But even as Turnbull blamed voters for not delivering a majority, the Australian Electoral Commission was issuing late night updates that moved several Coalition seats back into the doubtful column.

The Prime Minister’s enemies within his own party wasted no time in venting their vengeance. The melt-down in the Liberal Party began around 9pm.

@TextorMark Hey Tex, I’m thinking that Conservatives actually do matter.

— Cory Bernardi (@corybernardi) July 2, 2016

Cory Bernardi started tweeting Mark Textor. Textor started tweeting the Electoral Commission. Andrew Bolt let loose an anti-Turnbull thunderbolt from his blog.

This hugely enjoyable post was published at 10.07pm. It was entitled, simply, ‘Malcom Turnbull – You are Finished.’

The Coalition’s campaign was a mess. Turnbull went into a marathon campaign with little in the way of concrete policy proposals, aside from the chimerical $48 billion company tax cut.

When the “jobs and growth” message failed to bite, the Coalition switched to border security and asylum seeker rhetoric. By the end of the campaign, Turnbull was stressing “stability”, rolling out “stick to the plan” bunting on polling booths. This didn’t work either: there was no late swing back to the government – if anything, the swing to Labor remained stubbornly baked in.

The problem with telling voters to “stick to the plan” is that many apparently did not like the plan. They may well have simply been reminded of the fact that the government wanted to give tax cuts to companies – a policy that has never been popular.

Most critically, the Coalition was badly unnerved by Labor’s “Save Medicare” attack. As New Matilda’s Ian McAuley has argued here, Labor was perfectly correct when pointing out that the government planned to privatise the Medicare payments system. It was, indisputably, the government’s policy. But whatever the merits of the scare, Turnbull and his cabinet were utterly unprepared for a debate about health policy, and completely failed to re-establish the government’s dominant messages … or even to adequately debate Labor on health at all.

If the Coalition had a serious health policy, it could have rebutted Labor by pointing to its own. But it didn’t. So its only response to the accusation that it wanted to kill off Medicare was to claim “no, we’re not going to kill off Medicare”.

Similarly, the government lacked any semblance of a social policy vision. Everything was subordinated to economic policy, which in turn was resolutely pro-corporate and one-dimensional. Kristina Keneally makes an excellent point today about the Coalition’s grammar: “jobs and growth” is not really a policy. It’s simply a description. There’s not even a verb.

Zooming out, Turnbull could fall prey to Labor’s message that he was out of touch because he is out of touch. Turnbull is extraordinarily wealthy. He lives in a harbourside mansion. As I argued last year, this matters. But beyond the personal, Turnbull’s policies are out of touch. They are still, broadly, the policies of Tony Abbott and Joe Hockey. The electorate comprehensively rejected those policies in 2014, and it hasn’t changed its mind.

Turnbull’s sunny months of honeymoon were driven by the belief by voters that he would drag the Liberal Party to the centre on issues like marriage equality, climate change, and basic public services like hospitals and universities. Voters still want to believe in the centrist Malcolm Turnbull. But he hasn’t given them what they want: a broadly centrist government. Policy, not tactics, is the best explanation of yesterday’s anti-Coalition swing.

When Joe Hockey and Tony Abbott slashed funding to health and education, voters disapproved. When Malcolm Turnbull kept slashing funding to health and education, voters started to disapprove of him too.

In contrast, Labor comprehensively won the policy debate during this campaign. The ALP campaigned on a surprisingly positive platform, and advanced some big-picture ideas for the future of Australia. The party built on its strengths when campaigning to save Medicare and against $100,000 degrees, and there were some innovative policies to combat inequality, reform negative gearing, and curb the market power of oligopolies.

Turnbull may or may not be able to form government on the floor of the House of Representatives. But he now has very little political capital to spend. He will lead a diminished and divided party, with an enraged right wing gunning for his scalp and an ever-present Tony Abbott lurking in the background.

If Turnbull does lead a government with a majority of one or two, it will be a very difficult term of Parliament, as Julia Gillard well knows. Turnbull won’t be able to pass the bill to re-establish the Australian Building and Construction Commission. An uncooperative Senate is guaranteed. And then there are all the other looming issues: an uncertain economy, a budget in deficit, the marriage equality plebiscite.

While the Coalition flails, Bill Shorten is moving to seize the political centre. At a media conference this afternoon, he dismissed confected rumours of an ALP leadership challenge, and staked out Labor’s territory firmly in the centre-left of Australian politics.

Quipping about the “old Malcolm”, he even dared Turnbull to pass climate change and marriage equality legislation with Labor’s help.

All of this is ultimately the responsibility of one man: Malcolm Turnbull. He could have called an election last year at the peak of his honeymoon. He could have waited for a normal half-Senate election later this year. Instead, he has delivered an unworkable Senate, complete with dangerous demagogues like Pauline Hanson and Derryn Hinch, and accelerated the rise of minor parties.

The Prime Minister’s decision to go to a double-dissolution election was always a colossal gamble — just as I warned back in March. Now it has been revealed as folly.

And so Malcolm Turnbull now faces an awful truth: his political credibility is in tatters. He has lost any chance of an electoral mandate. His entire strategy has failed. Instead of winning an election and imposing his authority on the Liberal Party, he is fundamentally weakened, perhaps terminally.

To quote none other than Andrew Bolt (and believe me, I’m enjoying this): “And now look. Almost everything turned to ruin.”

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.