Around the world democracies are in crisis, as people turn away from major parties and institutions. This campaign may have been labelled boring, but its outcome is profoundly important, writes Ben Eltham.

They were voting at my local booth this morning in Thornbury, in the seat of Batman.

There weren’t many voters, mind you, but a slow trickle wandered in, generally singly, over the course of a half hour that I watched. Swaddled in puffy jackets against the freezing Melbourne south-westerly, a group of harried party operatives struggled to press how-to-vote cards into hands of voters before the wind snatched them away, sending the leaflets cartwheeling down the high street in a vortex of undistributed preferences.

Despite the imminent election on Saturday, the mood among party volunteers was cautious, rather than excited. Batman is one seat to watch this weekend, with the Greens’ Alex Bhathal poised to seize the metropolitan Melbourne seat from Labor’s David Feeney.

Bhathal is a throw-back to an older style of candidate: a genuine local running a genuine grassroots campaign. She has run in the seat for the Greens for five elections in a row, taking the party’s primary vote from single figures to 26 per cent in 2013. Her opponent, David Feeney, is the embodiment of ALP machine politics. A former senator, Feeney parachuted himself into Batman after doing a deal with Victorian Labor’s right-wing factions in 2013. His personal politics are well to right of the inner-north’s increasingly progressive and environmentalist tinge. As the beards and organic groceries proliferate, Labor’s chances in the seat recede.

Feeney has had a horrible campaign, studded with gaffes and oversights, like his astonishing failure to declare a $2.3 million house on the Parliamentary assets register. He has struggled in media appearances, leaving a set of sensitive internal briefing notes on a couch at Sky News. Labor headquarters eventually banned him for media appearances, sending him out on the hustings, where he could be hidden from journalists with inconvenient questions.

Every election ultimately devolves down into such battles, as the various parties fight it out across 150 federal electorates for control of the Parliament, and the right to govern Australia.

And yet, despite the manifest interest in some of these local battles, the weary truth of 2016 is that the dominant theme of the campaign has been disengagement.

It is no secret that this election has failed to capture the imaginations of many ordinary Australians. In June, press gallery veteran Michelle Grattan was arguing – convincingly, I think – that “people aren’t engaged with this contest.” Grattan added that “people have lost faith and trust” and that many are “opting out of the election”.

ABC columnist Tim Dunlop is another thoughtful commentator on the political scene. Writing about the Brexit referendum, he asked this week “how is it that in nearly every nation – including the richest and most technologically advanced – there is at this moment in world history, a white-hot core of anger and resentment that is threatening to tear apart the institutions of democracy and governance more generally?”

What drives the disengagement remains a mystery, even to those who study it.

Thousands of books, papers and PhD theses have been written on the matter; Radio National recently devoted a week-long series of episodes to the topic; the major parties themselves have their futures riding on finding a solution. But, as a glance at the querulous politics of contemporary western democracies tells us, no-one knows for sure what is driving the anger. Is it economic inequality? Increased immigration? The decay of once-stable social and familial bonds? Our increasingly selfish and atomised personal lives? Is it the stain of money, corrupting the political process for corporate gain? Is it the media? Is it politics and politicians themselves?

The slow hollowing-out of Australian party politics is the central theme of the commentary of the blogger known simply as The Piping Shrike. In a series of perceptive blog posts, this sharp political observer has pointed out that both major parties are increasingly moribund institutions, a shadow of the mass political movements they once represented.

“Both parties come to this election exhausted,” she or he wrote back in May, after the dreary first leaders’ debate. “The leadership toing and froing of the last eight years has solved nothing.” The Piping Shrike mounted an extended exposition of the thesis in Meanjin in March.

The problem now for parties is that the role for which they were formed has gone. The unions’ social weight has declined along with their membership to a minor force in the industrial relations landscape—so the social importance of Labor’s role in representing them has withered. And with the end of the unions as a force, so has the need by business to oppose them, and the role of non-Labor parties has also lost much of its meaning.

If we look at the increasingly unrepresentative nature of the two major parties, it’s hard to disagree. The Australian Labor Party under Shorten has been more unified and organised than during the disastrous Rudd-Gillard years, and has even shown signs of restoring some of its grassroots strength. But Labor is still a party run by factional elites. Shorten himself is factional boss, elevated to the leadership against the wishes of a majority of rank-and-file members.

Nor has the ALP shown any real sign of coming to grips with the existential crisis confronting the trade union movement. Union memberships continue to fall, and Labor’s old base in the industrial working class is withering. Across the world, parties of social democracy are struggling in the face of rising anger from the populist right.

Labor under Shorten has done remarkably well within a relatively narrow compass. The Opposition has won this campaign, easily besting the Coalition in the policy debate. There has been a welcome commitment to health, education and social services, to the arts and culture, and to restoring some of the damage wreaked by Abbott and Hockey.

But even if Labor grasps the importance of addressing rising inequality in our society, the ALP has left many nettles ungrasped. What should the party do about climate change? What should it do about carnivorous global capitalism? In an ever-more divided and atomised contemporary society, what is the stable support base for a left-of-centre party?

Things aren’t much better for the major conservative party. The modern Liberal Party is a husk of the great middle-class movement founded by Menzies. It is stubbornly white and male, in a country which is increasingly female and multi-hued. The political impetus of the Liberal base is far to the right of the bulk of the electorate, as the train-wreck of the Abbott government so ably demonstrated. Liberal moderates such as Turnbull, Arthur Sinodinos, Mitch Fifield, and Simon Birmingham must wage constant internal struggle simply to retain control of the party apparatus. The incipient civil war brewing over the marriage equality plebiscite will surely explode shortly after the election.

The Coalition, too, has few real answers to the pressing problems of our time. It is frankly demoralising that the major party of the right in this country believes that a $48 billion company tax cut constitutes a viable national economic plan. When it comes to housing affordability, the Coalition has actively sided with the old and the rich against the young and the renting. Inequality in the modern economy is either ignored altogether, or celebrated as a integral feature of neoliberal policy. When we consider the Coalition’s pet issue of fiscal policy, Scott Morrison has no credible plan to get the budget back to surplus any time soon. As for climate change, Turnbull has simply sold out his own principles, in a breathtaking accommodation with personal ambition.

Neither major party can address refugee policy, the festering moral sore on the national body politic. The Coalition continues to pander to the worst impulses of racism and xenophobia in the community, actively punishing innocent people for seeking a better life on our shores. Labor’s moral turpitude is perhaps worse: many in the party believe offshore detention is unconscionable, but the party is too scared of the electoral consequences to soften its position.

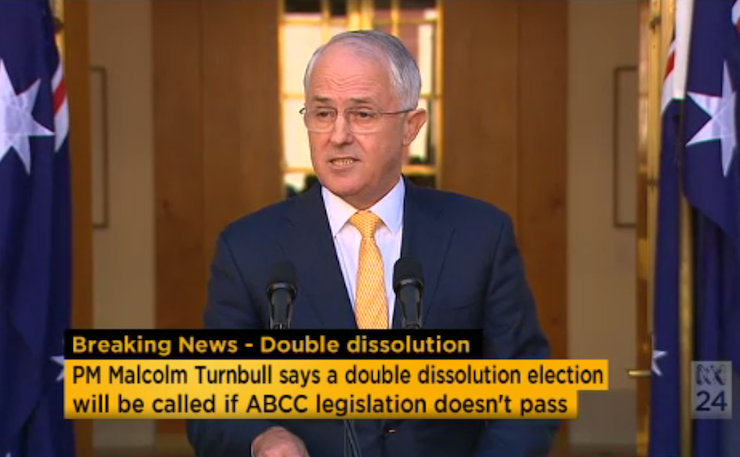

And then there were the lies and the disappointments. It’s instructive that at the end of this double-dissolution campaign, we’ve heard almost nothing about the issue Malcolm Turnbull used to trigger an early election: the Australian Building and Construction Commission, supposedly so important back in May. The double-dissolution move was completely unnecessary: it was always a viable option for Turnbull to simply wait for a normal election. Hailed by the media at the time as a master stroke, Turnbull’s casual dishonesty in calling an election on an issue that he then ignored is the sort of too-clever tactic that makes many voters hopping mad.

If there is a deficit of trust in this election, then our politicians can only blame themselves. It was Kevin Rudd’s decision to backflip on climate change that began his long slide to oblivion in 2010. It was Julia Gillard’s decision to break a promise on a carbon tax in 2010 that indelibly scarred her prime ministership for centrist and conservative voters. And no prime minister since Billy Hughes has broken as many promises, and as rapidly, as Tony Abbott managed to in 2014.

And so this election has seen long-running trends of disengagement continue. There is a growing suspicion of politics-as-usual. Voters remain disconnected, even hostile, to the practice of democratic politics. Some of this is attracting votes to minor parties and independents. But the broader sense of the election, even in highly engaged places like inner-city Melbourne, has been a mistrust of politicians generally, and a fierce scepticism towards the institutions of democracy themselves.

Voters face a time of economic uncertainty. The long boom of the Howard years seems long ago. But neither major party can restore the happy times, whatever their promises. And so citizens get disappointed, again and again. Can we be surprised that so many voters disdain the lies and the petty power games? So much of politics, and the way the media reports it, seems to have little to do with the pressing concerns of the average voter: paying bills, raising children, a stable job and the chance to get ahead in life. Confronted with the many betrayals of major politics, and the trivial and superficial way in which politics is often represented by the media, it’s entirely understandable that many turn away.

Politicians seem, in equal parts, disconnected and unreal: neither able to understand the concerns of ordinary people, nor able to raise the political discussion above the petty plane.

This may help to explain the strange paradox of the 2016 campaign. As I have consistently argued here at New Matilda, an awful lot is in fact at stake at this election, even if many voters don’t really believe that much can change. A long and often boring campaign has drained much of the passion and the colour, while the Coalition has continued to bleed support.

But if we zoom back from the overwhelming ennui that has gripped so much of the electorate, it is clear that critical issues are in play. The future of Australia’s health system, of our universities, of welfare benefits and pensions, of the ABC and public support for culture, of aged care, of foreign aid, of legal aid and community legal services, and of the right of all Australians to marry – all of these hang in the balance on Saturday night.

Labor should be commended for this election campaign. It has consistently presented a positive and optimistic view of Australia, and its economic policies are far superior to the Coalition’s (though many will never accept that). A Shorten government will act to repair the social safety net and invest in a decent system of public health and education. In the current political environment, these are laudable, even noble goals.

In contrast, a Coalition victory will see further austerity. Upward redistribution will further damage to Australia’s public sphere and common wealth. Australia will get meaner, and nastier. The policies of 2014 are, after all, still the policies of 2016, with an increasingly shop-worn Turnbull still struggling to sell them.

Unless it wins big on Saturday night, the Coalition will be more divided and politically weaker than it has at any time since 2013. The marriage plebiscite, if it ever happens, will see open warfare in the Liberal Party. In the wake of Brexit, the budget could continue to blow out. Malcolm Turnbull will struggle to unify a disunited party. There will be little political capital to spend.

In the wake of a narrow Turnbull victory, it is even possible to envisage a split in the Liberal Party. Given the events of the last eight years, it is surely no certainty that a re-elected Malcolm Turnbull will still be prime minister in 2019.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.