Cuba is a nation facing rapid change. Researchers Shannon Brincat and Samid Suliman found a people proud of their past, and optimistic about their future.

The 7th Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba was recently held amidst a profound period of change for the Cuban people. The most significant outcome was the promise of the “systematic rejuvenation” of the country’s political system, most notably through the proposal of term-limits – two five-year terms for officials – that would effectively end the rule of the Castros after Raúl turns 86.

Other changes to political structure were largely guessed well before the Congress: Raúl Castro elected as First Secretary, Jose Ventura as Vice President, and no radical reformers linked to the 15 member Politburo.

Perhaps more remarkably, major economic changes were discussed, such as ending the rationing system, reduction of the public sector, and even discussions of deregulation.

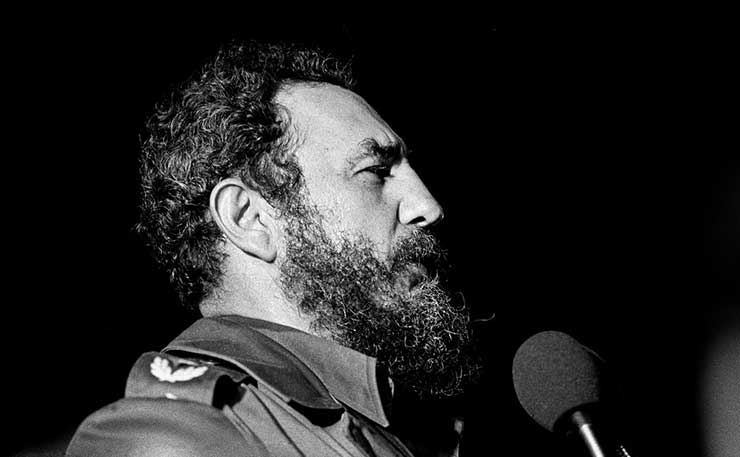

Whilst Raúl Castro declared that the concentration of property in private hands would not be allowed, whether this can be maintained remains to be seen. Here, Fidel Castro’s valedictory speech illuminates much about the mood and type of change underway in Cuba – a period in which the old revolutionary generation stays in power (for the time being), whilst broader economic and social changes – spearheaded by normalizations of US-Cuba relations – go on apace.

As two critical international relations researchers, we have been interested in the implications of this period of change in Cuba-US relations.

We had planned to be in Cuba to talk to professionals about how they perceive, understand, and speculate on this transition period and what it may mean for the future of the Cuban people.

Fortuitously, our recent visit coincided with that of the first American President on Cuban soil since 1928. With the help of two trusted translators, we interviewed some 20 professionals in both Havana and Santiago de Cuba: doctors, lawyers, journalists, scientists, and self-employed ‘entrepreneurs’.

The professional class are a crucial demographic, making up a large part of the public ministries and emergent private sector. Given the high levels of education in Cuba – where some 13 per cent of its national budget goes to education (compared to the 5.5 per cent spent in the US), with at least 125,000 in higher education in any one year – this group is an important representative sample of how educated citizens are viewing the changes underway in their own country.

Our observations matched neither the resounding promises of Obama’s visions of Cuba’s future, nor the Western depictions of the strident socialism of Fidel. Rather, in our discussions, we found a buoyant hope for the future of openness matched by a keen awareness of, and pride in, the historical achievements of the de-colonial and socialist roots of Cuban independence, of which the 1958 revolution is only one part.

The question is whether these two futures – more open relations with the US, and the maintenance of the socialist project – are compatible.

A History of Imperialism

Discussions between the US and Cuban governments had taken place for some three years leading up to the public reconciliation. Diplomatic relations had resumed in late 2014 and, despite opposition from Cuban-American Republican lawmakers, Obama continued with his vow to “cut loose the shackles of the past”.

Many Cuban professionals whom we spoke to saw him as “brave”, indeed, they widely applauded the President’s “social intelligence” and eloquence.

Yet, the ‘shackles’ of the years between presidential visits to Cuba have been marked by incredible tensions. The strategic rivalries of the Cold War and the ideological battle between communism and capitalism loom large in this story.

But the rupture between these neighbours – only 90 miles apart from each other – has far deeper roots in Cuba’s independence movement. It is to this story that many of our conversations with Cuban professionals turned to as the focal point.

When on the verge of finally freeing itself from Spanish rule in 1902 after decades of armed struggle, Cuba was occupied and made subject to the Platt Amendment. This agreement permitted US military intervention in Cuban affairs, and set the foundation for the perpetual leasing of the Guantánamo Bay site in 1903.

1903 also saw the promulgation of the Reciprocity Treaty, which governed trade relations between Cuba and the US in subsequent decades. American companies were already heavily invested in Cuba since the early 1890s, and this Treaty helped to further entrench US commercial interests in the sugar, agricultural and banking sectors, among others.

The United Fruit Company (now known as Chiquita Brands International) was a notable beneficiary. Then came the Second Occupation of 1906, after which successive Cuban presidencies were marked by revolts, and usually followed by US military interventions to protect US economic interests on the island.

Foreign dominance over the entirety of the Cuban economy rankled, and was a key issue driving the political revolution half a century after formal US occupation ended.

As a museum curator bluntly surmised for us, Cuba was neither “free” nor “independent”.

The 1958 revolution is still seen, at least for most Cubans that we spoke to, as the culmination of the previous century’s independence movement. Its decidedly anti-colonial goal was the sovereign independence of Cuba; communism a later development born of isolation and economic necessity.

It was far more about Martí than Marx. And it remains so today. As a scholar of jurisprudence in Santiago expressed to us, what the Cuban citizen recognises as the law are those actions that “defend” the gains of revolutionary independence.

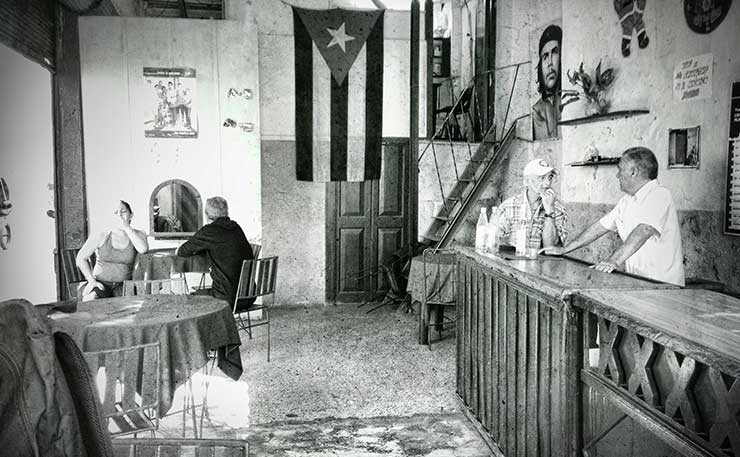

It must be realised that what Cuban citizens regard as ‘the revolution’ is not what we assume it is in the West – it is not the Communist Party per se. Rather, it is the world-class health care, free education, women’s rights, and racial equality to which all Cubans have become accustomed.

All four of these gains are seen as fundamental pillars of Cuban society; Cubans do not want to lose these important social goods, and do not see the US brand of liberal democracy as a way to guarantee them for the future.

Yet, across the Gulf, initial support of this vision of Cuban freedom, and for Castro, was quickly washed away by the tide of anti-communism. Along with it, this longing for independence by the Cuban people has since been largely forgotten by its Northern neighbor.

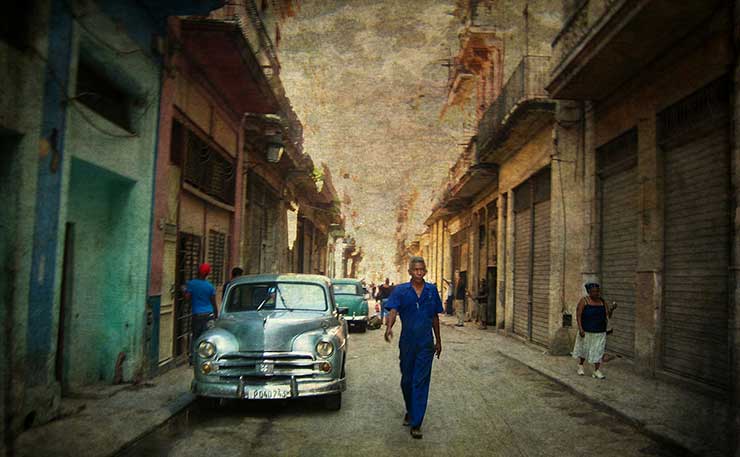

Yet Cubans are reminded of it every time they pass a statue of a national hero or revolutionary slogan. Independence is, literally, around every corner.

Obama’s visit was to do away with all this, to “bury the last remnant of the Cold War” and “look to the future with hope.” But Obama’s refusal to be “trapped” by history in order to move forward was seen as disingenuous by many of those we spoke to.

That is, Obama’s call “to leave the past behind” was not a forgetting of history, but rather an effacement of history. For Cubans, the hope of reconciliation lies not in removing this “shadow of history” from Cuba-US relations, but to recognise it and live with it.

For Cubans, moving forwards must mean the forgiveness, not forgetting, of historical wrongs. In order to forgive, this history has to be first acknowledged.

What do Cubans Want?

Obama’s visit was, in no small measure, motivated by the faith in the opportunity posed by the opening of Cuba’s economy to the region, to the world, and to its own people.

In his address at the Gran Teatro de la Habana, the US President was sanguine about the future, and the role of Cuba’s cuentapropistas therein.

While he emphasized the importance of Cuba finding its own way in the world market, the fact that he was accompanied by a retinue of courtiers – a Congressional delegation, entrepreneurs and journalists – speaks volumes about the message Obama intends to convey to his own constituency.

Clearly, a market of some 11 million eager and well-educated citizens is Cuba’s la fruta Madura of today – something keenly recognized by wealthy investors across the Gulf. Promises of ending the embargo, expanding tourism, and infrastructure development projects, are just the first economic benefits to be won for those with foreign capital.

But what do the Cuban people want?

Media reporting seems caught between two equally paternalistic assumptions on this question.

On the one hand, there is the view that Cubans cannot wait to do away with Castro, the revolution, and socialism and embrace a full-blown market economy. On the other, there is the view that Cubans are so oppressed by Castro and communism that they have no knowledge of their own agency and destiny but need help from outside.

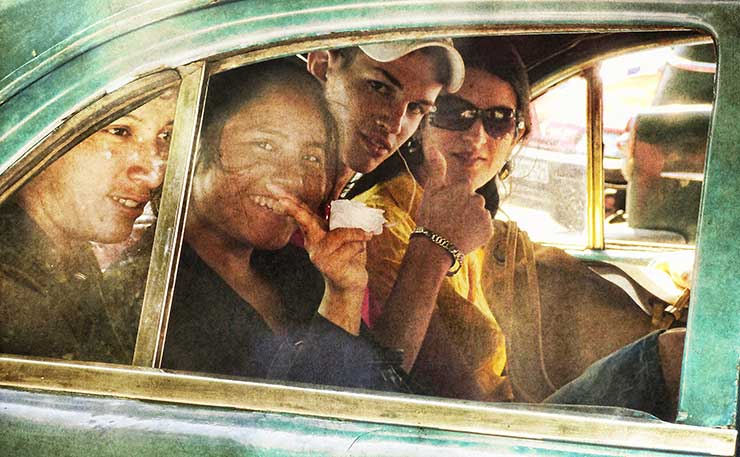

The reality is quite different. What we found is a fully aware, resilient and strong populace that wants to retain independence, key social benefits, and who desire future economic improvements on their own terms.

In these new relations with the US it is about “sticking to your principles,” as a journalist from Santiago told us.

All want to see a “peaceful” change of relations centered on ending the embargo. For it is not under-development, nor lack of goods, but low wages that restricts their purchasing power.

All professionals have to supplement their extremely modest income by other means and whilst this has eased a little since the Special Period, it is still the key issue.

Whether a vascular surgeon or university professor, none make a wage from which they can afford simple luxuries. Thus, easing bureaucratic red tape, promoting small enterprise, and ending the embargo are key priorities for expanding economic opportunities.

However, this should not be confused with a desire to transition to a market economy. Rather, most want the gains of the ‘revolution’ to be retained. So, there is a strong degree of caution amidst the hubbub of Obama’s visit: after all, the future promises have not yet become concrete changes.

Cubans are only too well aware of the constraints upon Obama’s agenda for change, which include the looming US election, the Trump phenomenon, a hostile congress, and Obama’s own ‘lame duck’ status.

So far, despite the symbolic meeting, not much has changed in ordinary Cubans’ everyday life. But change does loom on the horizon.

Thinking beyond ‘development’

Cubans are moving into this future with their eyes wide open. Their hope is tempered by a healthy dose of dubiety. While Cuba’s future is uncertain, it is essential to resist the urge to see Cuba as a backward society in need of intervention from the West to sort out its development problems.

Cuba has always been, and continues to be, a place that produces skilled, knowledgeable, and passionate professionals – who think and act beyond the geopolitical embargo.

It is high time we look to the political and imaginative resources already abundant in Cuban society, and resist the temptation to diminish the fiercely social understanding of political independence that has driven Cuban society in the face of hardship and uncertainty over centuries.

At the same time, we should resist the urge to think of this period of transition as just a one-way street.

As a self-employed professional in Santiago questioned, “which one is the better, which is the correct way to think?” In response, our translator quipped, “Maybe it is the Americans who can learn from us?”

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.