At least one young man’s life is in ruins for talking tough on the internet. Meanwhile, police and politicians beat their chests. Michael Brull explains the insanity.

The indefatigable Paddy Gibson, senior researcher at Jumbunna at UTS, posted this story on Facebook on Thursday. At first glance, I assumed it would be the usual uninteresting account of terrorism allegations against a young Muslim. Sourced from AAP and Adam Cooper, it warrants a closer look.

After various terrorist attacks, we often hear that the Federal Government is going to crack down and pass new legislation that finally gives them the power to go after The Terrorists. This story gives us a little insight into what this means in practice.

The young man in question is Sevdet Ramadan Besim. He is 19-years-old, and apparently used to live in south-east Melbourne. The boilerplate stuff – the kind that makes it sound like police have successfully foiled a menacing plot – is this: “Sevdet Ramadan Besim, 19, of Hallam, is accused of plotting an Anzac Day terror attack in Melbourne that would have included a beheading. He was committed to trial in the Supreme Court on Thursday after pleading not guilty to four charges.”

The alleged plot is mentioned at the start. That is, Mr Besim “allegedly discussed packing a kangaroo with explosives, painting it with an Islamic State symbol and setting it loose on police officers.”

Er… what? Does anyone think this is an actual, serious, literal thing that was going to happen?

Some readers might think, ‘Well, if you had a group of people, they knew where to find kangaroos, had experience in handling animals and so on….’

Okay, so what are the four charges against Mr Besim? The story says they “included conducting internet searches of Anzac Day in Melbourne and Dandenong, engaging in communications and creating an electronic memo on his phone – all in preparation for a terrorist act.”

Those are three of the charges. Now get this. Every single one of those acts – not one of them in particular – every single one of them, if proven, carries a penalty of at least 15 years prison. Possibly even life imprisonment.

Creating an electronic memo – 15 years imprisonment.

Engaging in communications – life imprisonment.

Internet searches? Life imprisonment.

Anyway, the story has some more details about what police claim was actually happening. They allege, “Mr Besim and a person overseas had been in a series of communications in the lead-up to the alleged plot for Anzac Day.” That is, apparently Mr Besim didn’t conspire with anyone in Australia. He spoke to someone on another continent. Which makes the kangaroo plot sound a little less likely. To recap: a 19-year-old claimed to someone overseas that he was going to wire a kangaroo with explosives, paint it, and then make it target cops and blow them up.

Who is the overseas person? In July last year, a 15-year-old boy in Britain pled guilty to incitement, as he urged Mr Besim to “get your first taste of beheading”.

Thursday’s story has some of Mr Besim’s completely serious internet planning, presumably with the British 15-year-old. Mr Besim allegedly said he was “ready to fight these dogs on there [sic]doorstep”, “I’d love to take out some cops”, and “I was gonna meet with them then take some heads ahaha.”

For those not in the know, “ahaha” is secret Islamic State code, indicating seriousness and gravity, and is not at all to be taken as a sign of levity and possible shit-talking from a 19-year-old to a 15-year-old.

The one charge that was dropped was this: “one count of conspiring to do an act in preparation for or planning a terror act, which carries a maximum sentence of life in prison.”

I suppose they didn’t think they could prove Mr Besim was actually conspiring to do anything. Fortunately for the prosecutor, Andrew Doyle, the bar is low enough that he won’t have to worry too hard about whether he can put Mr Besim away for a long time.

Are the terrorism laws really so draconian?

Australia’s terrorism laws

The Attorney General’s website offers a brief guide. It explains that:

“It is a terrorist act offence to:

- commit a terrorist act

- plan or prepare for a terrorist act

- finance terrorism or a terrorist

- provide or receive training connected with terrorist acts

- possess things connected with terrorist acts

- collect or make documents likely to facilitate terrorist acts.

A person may be convicted of a terrorist act offence if they:

- intend to commit one of these offences; or

- were reckless as to whether their actions would amount to one of these offences.

Furthermore, “A person may still commit a terrorist act offence even though a terrorist act did not occur.” Now, “plan or prepare for a terrorist act” may well be the internet searches and internet communications. “Possess things” may cover the electronic memo.

Furthermore, it doesn’t matter if the person intends to commit one of those offences. It is enough that they are reckless as to those actions.

If that gives you some worry, the Human Rights Commission observes that, “The definition of a terrorist act has been criticised as being so broad its meaning is unclear.” Broadly, it is an action or threat of action, undertaken to advance some type of cause through intimidation or coercion of the public or government. The action needs to cause serious physical harm, endanger someone’s life, create a serious risk to public safety, and so on.

Let’s turn to the legislation. Firstly, let’s consider the “things” that can send someone to prison. The Criminal Code provides as follows:

101.4 Possessing things connected with terrorist acts

(1) A person commits an offence if:

(a) the person possesses a thing; and

(b) the thing is connected with preparation for, the engagement of a person in, or assistance in a terrorist act; and

(c) the person mentioned in paragraph (a) knows of the connection described in paragraph (b).

Penalty: Imprisonment for 15 years.

Okay, so if someone possesses a thing, and it’s connected with assistance in a terrorist act, then 15 years prison. The person has to at least know of this connection.

However, in a later subsection, it explains that if that person is “reckless as to the existence of the connection” between the “thing” and the act, the penalty is 10 years imprisonment.

It is then explained that it doesn’t matter if the “terrorist act does not occur”, and it also doesn’t matter if the thing is not connected with a “specific terrorist act”. So if two idiots on the internet discuss killing white people because they think it’ll impress Daesh, because they want to sound tough, and one of them is stupid enough to create an electronic memo – or a word document, or whatever – to save that conversation, that may mean 15 years imprisonment.

HOUSE AD – NEW MATILDA IS A SMALL, INDEPENDENT MEDIA OUTLET. MOST OF OUR STAFF AND WRITERS ARE UNPAID. IF YOU WANT TO HELP SUPPORT INDEPENDENT MEDIA, YOU CAN DONATE A COUPLE OF DOLLARS TO OUR POZIBLE CAMPAIGN HERE OR SUBSCRIBE TO NEW MATILDA HERE.

After all – what is preparation? How early in the process of a plot is preparation? Surely, preparation is before the serious planning stage. Especially if planning and preparation can occur before a specific target has been chosen.

Is it googling things that you might want to target? Is it fixing the internet so that you can google your targets? Is it getting a new computer, or new modem, or new wires, or an extension cord for your computer – so that you can google prospective targets?

Remember – the offence relates to a thing connected with preparation for a terrorist act that doesn’t need to happen, or even be a specific thing that was going to happen.

And as we have seen – these are all separate acts. So if one idiot creates three electronic memos, that can mean 45 years prison.

The “possesses a thing” provisions are repeated for the offence of collecting or making a document with the connection described above. As above, doing so intentionally attracts a 15 year jail sentence, as opposed to recklessness carrying 10 years. Doesn’t matter if the act doesn’t occur, it’s not connected to a specific terrorist act. These too could capture the electronic memo.

And then, just in case the provisions above aren’t broad enough, “A person commits an offence if the person does any act in preparation for, or planning, a terrorist act.” The punishment is imprisonment for life. Doesn’t matter if the act doesn’t occur, or it’s not in preparation for a specific terrorist act. Now, what is any act in preparation for, or planning a terrorist act? If conducting an internet search suffices, what else might? Recommending a search engine to someone?

Talking about how broad and ridiculous the laws are can distract from the human element. So let us return to the story.

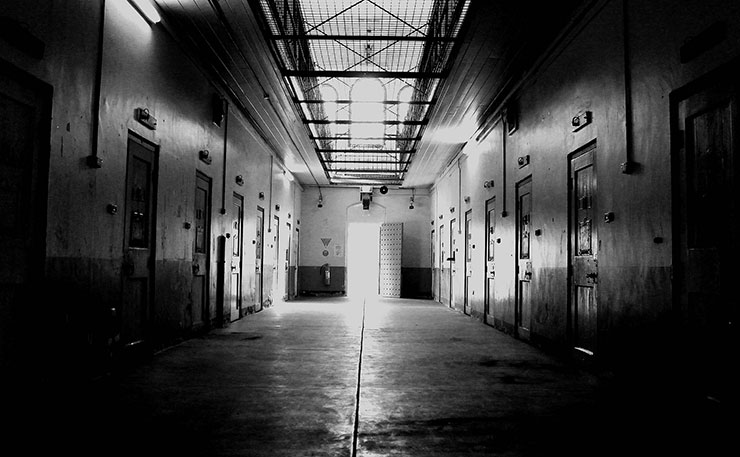

It reports: “Mr Besim has been in custody since April 18 when 200 heavily armed officers swooped on the city’s south-east, arresting five teenagers and seizing knives and swords.”

200 heavily armed cops. At 3:30am. And because of that, Mr Besim has been imprisoned since April last year. That’s almost 10 months in custody already, because of what Besim is alleged to have said to someone overseas. And the internet search, and the electronic memo.

What else remains of those raids? It took “200 heavily armed” cops to yield three young men arrested and charged. Besim – and his internet searches and electronic memo – are one of those three.

Another is Mehran Azami, a 19-year-old who wasn’t charged with terrorism offences, but who pled guilty to importing knives and knuckledusters.

The third is Harun Causevic, an 18-year-old, against whom the police dropped all charges.

Incidentally, all of those arrested were “associates” of Numan Haider. Haider was shot dead by police after stabbing police officers. Perhaps this is why they were caught in private communications saying unpleasant things about police.

The 200 heavily armed police also arrested two other teenagers, against whom no charges were laid. Three of the teenagers were injured during the arrest process, with one sustaining a head wound. Presumably, the 200 heavily armed police were only defending themselves against the teens.

The Hun was duly impressed by the triumph over terrorism. After all, police said their raids thwarted “An Islamic State terror plot to kill law enforcement officers with knives and swords in Melbourne on Anzac Day”. Relevant officials basked in the glow of their heroism.

For example, Acting Deputy Commissioner Shane Patton: “Safety should always be the priority and today we have acted swiftly to disrupt an attack intended to bring harm to everyday Victorians going about their business.”

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews: the alleged terrorist plot was “simply evil, plain and simple… together with Victoria Police, Commonwealth law enforcement and intelligence agencies, the Victorian Government continues to take reasonable and necessary steps to keep every Victorian safe.”

He also promised to increase funding for police in countering terrorism. So it seems everyone involved in these efforts to subvert Mr Besim’s diabolical plan looked good, and counter-terrorist forces got more money and positive publicity, which I imagine they’ll put to more good use.

None of the above requires any particular knowledge or expertise. The fact that Mr Besim might be imprisoned for the rest of his life without having ever harmed anyone, and it seeming unlikely he would ever harm anyone, is not even slightly hidden from the public. It just isn’t the kind of story that gets traction in Australia.

When the police launch dramatic raids, and politicians start jockeying to secure political capital from it, it’s a big story, and right-wing hacks get a chance to warn about what this shows about the Muslim threat.

When it fizzles out – well, what is the story anyway? It’s complex, it’s not part of the news cycle, and there will probably be more threats down the road anyway. The fact that a young man’s life has already been ruined is one of many left by the way.

All this may not make us any safer – how can it, when it’s unlikely these teenagers posed any threat in the first place? – but it offers plenty of benefits to the people who get to announce the plot that has been foiled.

Just about every day, people across Australia communicate threats on the internet. The terrorism rubric seems to be a fancy and elaborate way to drastically lower the bar for prosecuting such threats, and imposing significantly heavier penalties for those threats, and even heavy penalties for extremely non-consequential connected “things”.

HOUSE AD – NEW MATILDA IS A SMALL, INDEPENDENT MEDIA OUTLET. MOST OF OUR STAFF AND WRITERS ARE UNPAID. IF YOU WANT TO HELP SUPPORT INDEPENDENT MEDIA, YOU CAN DONATE A COUPLE OF DOLLARS TO OUR POZIBLE CAMPAIGN HERE OR SUBSCRIBE TO NEW MATILDA HERE.

And yet, the bar is lowered and the penalties are strengthened in cases where the threats just happen to be made by Muslims.

All this cries out for public debate, at the very least. Yet small stories, like the one about Mr Besim, quietly fly under the radar, as news breaks once again of counter-terror raids in Melbourne. Raids which reinforce in the public mind the serious threat posed by Muslims.

One final point. When a terrorist who identifies as Muslim kills someone, it is expected that Muslims, and Muslim leaders in particular, will condemn the action. In so doing, they are expected to show solidarity with the rest of Australia.

Yet when stories like this are reported, non-Muslims are not expected to know or say anything.

Whilst 65 per cent of Australians think Muslims “should be doing more” to condemn terror attacks, the question doesn’t even arise as to whether Australians are doing our part to address systemic racism against Muslims.

It has been said that irreverence for authority, support for the fair go, and sympathy with the underdog are characteristic Australian traits. Where are those traits when stories like those of Mr Besim get reported?

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.