We now have a new Prime Minister. What does this mean for Australia? Trying to make sense of Malcolm Turnbull at this point is not an exact science. People can pick out different pieces of evidence, which don’t all point in the same direction. It will always be easier to review his record as Prime Minister once it is completed than when it has merely begun.

Thus, to get a sense of our new Prime Minister, I propose to review a few things in this article. Firstly, his electorate. Secondly, his personal record and characteristics before politics. Thirdly, early signs of the type of Prime Minister he intends to be. Finally, the reactions of various parties to his overthrow of Abbott, and what those reactions indicate about people who have followed his behaviour as a politician closely.

Wentworth

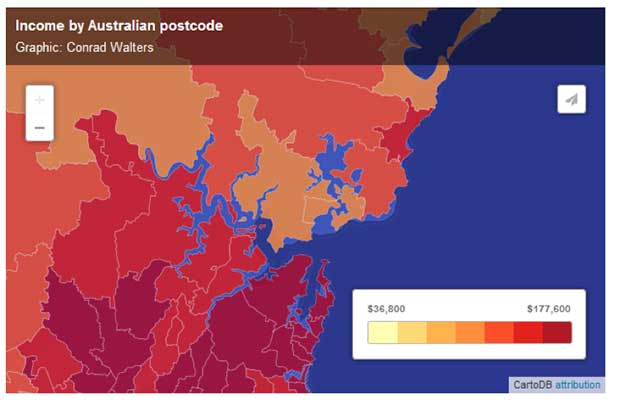

Malcolm Turnbull represents Wentworth in the eastern suburbs of Sydney. In May this year, the Sydney Morning Herald reported on the 10 richest suburbs in Sydney. Five of the postcodes were in Wentworth. If you look at income by Australian postcode, Wentworth is generally more affluent than Tony Abbott’s seat of Warringah.

Wentworth is also a place with generally high costs of renting.

Indeed, according to realestate.com.au, of the 10 most expensive suburbs in Australia, five are in Wentworth. Whilst not everyone in Wentworth is wealthy, Wentworth is a safe seat for the Liberals because it represents the interests of an electorate which is generally quite economically privileged.

Turnbull himself lives in what Domain describes as a “vast waterfront estate” in Point Piper, similar to a nearby mansion which sold for $52 million.

Point Piper is described by realestate.com.au as “Australia’s most exclusive suburb, the waterside enclave is home to the rich and powerful”.

This is perhaps the natural home for Turnbull. According to the Australian, he was the only politician to make the BRW Rich 200 in 2010, with personal wealth of $186 million. Perhaps the next wealthiest at the time was Kevin Rudd and his wife Therese Rein, at $56 million.

Turnbull’s personal wealth is not necessarily a guarantee of anything. However, his electorate does matter, because Members of Parliament are accountable to the people they represent.

Obviously, not everyone in Wentworth votes Liberal. Highly placed sources have confirmed that at least one regular columnist at New Matilda is a Wentworth voter, who has never voted Liberal.

Yet Wentworth is a safe Liberal seat for a reason: because the voters in Wentworth tend to vote in support of their own financial interests. If Turnbull decided he wanted to, for example, raise taxes on the rich, or pursue policies inimical to the interests of the banks or giants corporations, there is little doubt that there are plenty of rich and influential people in his electorate who would find a way to toss him out.

Another distinctive feature of Wentworth is its large Jewish population. The Executive Council of Australian Jewry responded to his elevation by observing that since 2004 Turnbull has represented an electorate with “the largest Jewish community in New South Wales”.

In the last 11 years, Turnbull has built a strong relationship with many elements of the Jewish community, and its major organisations. He has been a staunch defender of the Israeli government.

When there was discussion about amending the Racial Discrimination Act, Turnbull took a moderate position on how it could be reformed, whilst doing what he could to reassure the Jewish community.

Otherwise, Turnbull has also raised the possibility of Jewish ancestry on his mother’s side, and has been known to casually throw Yiddish words into his conversation, and even critique the wisdom of the Jewish theologian and philosopher Maimonides. Thus, as will be seen, it is little surprise that the Jewish community has been kvelling over the rise of Malcolm.

In terms of domestic policy, the issue of hate speech reform has essentially been killed off by the incompetence and cynicism of the Abbott and Brandis duo. Turnbull will probably back Brandis’s attempt to more strictly regulate racist speech, which appears to have been driven by the NSW Jewish Board of Deputies concern at a speech made by Hizb ut-Tahrir.

It is possible Turnbull will be interested in limiting the ambit of the proposed new law, but he will be careful not to antagonise the Jewish community.

In terms of foreign policy, Turnbull has competed every election with Labor candidates by promising to be the most loyal to the interests of the Israeli government. Now that he is Prime Minister, he will need to temper his advocacy for Israel with a desire not to alienate other electorates, such as the western suburbs of Sydney that seem to feature in every election analysis.

However, his foreign minister Julie Bishop is already pretty far out on the pro-Israel side of the spectrum, as was Tony Abbott. The so-called opposition is very unlikely to challenge Turnbull on this, especially the new domesticated version of Shadow Foreign Affairs spokesperson Tanya Plibersek.

The biggest change we might see in foreign policy is moderating the outreach and rehabilitation of the Iranian government that has occurred under Bishop, which has probably alarmed the major Jewish organisations. This too will need to be weighed up in terms of American foreign policy and the war against Daesh.

Malcolm before politics

Turnbull’s life before politics was discussed by Fortune. It reported that he started as a journalist, before becoming a lawyer and founding his own firm in 1986. His wealth came from “the strength of his stake in local internet service provider OzEmail, which he sold for around $60 million to Worldcom in 1999. After his legal career, he would pivot again to a new occupation as an investment banker, starting his own firm in 1987, and then leaving to become co-chairman of Goldman Sach’s Australian unit from 1997 to 2001.”

Matt Taibbi famously explained in 2009 his theory on Goldman Sachs: “The world's most powerful investment bank is a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money. In fact, the history of the recent financial crisis, which doubles as a history of the rapid decline and fall of the suddenly swindled dry American empire, reads like a Who's Who of Goldman Sachs graduates.”

Fortune also reports that Turnbull was “entangled in the collapse of HIH, Australia’s then-second largest insurance company. In December 2000, on the back of bulging debts and marginal solvency, HIH would become the largest corporate collapse in the country’s history, with liquidators estimating losses of up to $5.3 billion.”

Turnbull, in his capacity at Goldman Sachs, was the “primary adviser to FAI”, whose chief executive was Rodney Adler. HIH took over FAI for $300 million, but its assets were “grossly misstated”.

Turnbull was accused of concealing from the FAI board that he was working with Adler to take the company private. Adler was later jailed, but the Royal Commission cleared Turnbull and Goldman Sachs of any wrongdoing.

Four Corners reported that Turnbull has “been unable to put behind him the allegation that he played a role in Australia's biggest ever corporate collapse.” 15 years later, there has still been no smoking gun found. Whilst Turnbull may be associated with the collapse and corporate criminality, it is unlikely any serious proof of wrongdoing will ever be found.

Perhaps the most troubling profile of Turnbull was provided in this 5000 word profile by John Lyons in the Good Weekend, from 1991. It shows that Turnbull has made many enemies, which by itself wouldn’t establish much. And yet, two alleged that Turnbull threatened violence against them.

Journalist Richard Ackland was told, “Come outside and we’ll fix it up”. Lawyer Bill Conley claimed also that Turnbull threatened to take him outside and punch him.

Aside from that, the word “threat” appears in various forms 10 times in the article. As in, threats to sue for defamation, threatening to have journalist Neil Mercer sacked from Fairfax for writing critically about Kerry Packer.

The word “fear” appears six times. For example, “some business people fear him for what they say are his threats to sue them if they speak about him… Packer once quipped to a friend that Turnbull frightened even him”.

Or the reason “many people” fear Turnbull is, “They feel that if they upset Turnbull, they upset Packer, or so the conventional wisdom goes, and upsetting Australia's richest man, with a direct line to the Prime Minister, is not smart business.”

Lyons reported that “Even some of Turnbull's friends were careful about commenting. The spokeswoman for Gary Rice, new head of Ten, said, ‘Gary's very wary about doing this sort of piece.’” Turnbull allegedly also threatened an injunction to prevent publication of the profile.

Aggression also comes up repeatedly. His friend Bruce McWilliam claimed, “I'm sure even he would recognise he's too aggressive.” Lyons reported: “Turnbull's detractors say he is overbearing, unnecessarily aggressive. His friends say this is how he gets results.” In his own version of a dispute, he noted: “At the same time they say, hire Turnbull because he's really tough and aggressive and will do anything to get what he wants”.

Lyons also gives a sense of the extraordinary power that Turnbull seems accustomed to being around, and indeed wielding. For example, his powerful friends: “his first patron, Australia's wealthiest man, Kerry Packer; his business partner, ex-NSW Premier Neville Wran; his father-in-law Tom Hughes QC, perhaps Australia's most eminent silk.”

Or this account: “Early 1987. Four of the most powerful men in Sydney meet in a stunning apartment in Sydney's Elizabeth Bay. It belongs to Kerry Packer; his semi-private hideaway where he sometimes does business. In the room are Packer, Turnbull, Wran and Nick Whitlam, former head of the NSW State Bank and the son of Gough Whitlam. They begin discussing how to set up a bank: deregulation frenzy is in the air and, with foreign banks coming in, the four men want a cut of the action. Packer tells them he will kick in $25 million and Larry Adler, then head of insurance group FAI, will do the same. Over mineral waters, a new bank is born.”

Or this account of Turnbull’s power: “He wanted Westpac, the Ten Network's main banker, to sack then network head Steve Cosser and install Gary Rice. Rice is now head of Ten.” Or, “Turnbull and Wran's cleaning company, Allcorp, lost in a tender a contract to a competitor, Tempo, to clean a State Bank building. Three days before Tempo was to begin the contract, a State Bank officer rang a Tempo executive: Tempo no longer had the contract, Allcorp would be retaining it, even though Tempo consultant James Cook claimed it had bid up to $70,000 a year less than Allcorp.”

Among the rich and the powerful, corporate fighting is a blood-sport. It appears that Turnbull made himself quite at home in this world. Whilst the aggression recounted in Lyon’s article is from 24 years ago, it was published when Turnbull was “at 36, one of the most powerful lawyers in Australia”.

Whilst it is unlikely similar allegations of violent threats are likely to surface anytime soon, they also indicate a sort of ruthlessness not quite as charming as his present public persona.

The story also notes that Turnbull is also a man of considerable brilliance. Consider the 1986 Spycatcher case, in which the Thatcher government tried to prevent publication of the book.

Though “three Australian QCs advised” that the case could not be won, “Turnbull, then only 32, successfully took on a phalanx of British QCs.”

Turnbull’s advocacy in this case has led some to claim that he is a long-established supporter of freedom of speech. Such a position is hard to square with his reportedly numerous threats of defamation actions. Whether or not he continues to make such threats as Prime Minister will be a clearer indication of his attitude to freedom of political expression.

An early test will be a soon-to-be released biography of Turnbull. Another will be how far journalists can get in discussing aspects of his past, such as the allegations he was cleared of by the Royal Commission.

Other aspects of Turnbull that receive praise from those who would otherwise be unlikely to vote for the Coalition are typically thinly veiled proxies of class bias. Even among many Liberal voters, Tony Abbott was regarded as an embarrassingly gauche Prime Minister. He was vulgar, didn’t believe in science, engaged in faux pas, and was a reactionary, old-fashioned conservative who embarrassed us in front of enlightened liberal opinion in the New York Times, the New Yorker, and Foreign Affairs.

Turnbull, on the other hand, will be acclaimed as someone who is sophisticated, urbane, erudite, classy and so on – most of which is basically code for having received the proper class training.

I thought the day would never come when I’d say such a thing, but I think Miranda Devine captured this attitude. She observed that, “They don’t wince when he opens his mouth. They can imagine themselves being invited to dinner parties at his Point Piper mansion overlooking the glittering harbour. They anticipate with pride his bustling self assurance on the global stage, whether in New York addressing a UN conference or swanning around a climate change conference in Paris, talking up technocratic solutions to theoretical problems.”

By all accounts, Turnbull is capable of great charm and persuasion. Around 2005, he addressed the local chapter of Amnesty International in Paddington. Predictably, we were not entirely pleased with the Federal Government, which had let David Hicks rot in Guantanamo for years.

Turnbull wouldn’t commit to saying or doing anything, but he made clear that he regarded the treatment of Hicks as unacceptable, and somehow managed to charm at least some in our group, despite having committed to nothing in the time he spent with us.

Unlike many other politicians, he has offered serious intellectual substance in his discussion of political issues. For example, he spent a morning chatting with Robert Manne, intelligently reviewing an array of political issues like American politics and the wars on Iraq and Afghanistan.

Or on this speech on the Magna Carta and the rule of law, Turnbull’s footnotes include references to Locke, recent case law on the treatment of detainees at Guantanamo Bay, and a reference to two pages in volume five of Winston Churchill’s six volume study of World War 2.

Turnbull is a man of considerable erudition and intellect, and has not been abashed in demonstrating this.

Early indications of the new direction of the government

Some may look to Turnbull’s earlier forms of political advocacy as suggestive of where he may go as Prime Minister. Before running for Parliament, Turnbull led the campaign for Australia to become a Republic. He has also indicated his support for gay marriage, and famously lost his leadership of the opposition in 2009 through internal party discontent over his position on climate change.

There are a few points to make about this. Firstly, gay marriage and a Republic are somewhat politically safe among enlightened liberal opinion and the intelligentsia, even if many conservatives would feel otherwise about these issues.

Whilst this is not quite a populist approach, the Republic is an interesting issue on which to campaign. It is mostly symbolic, and suggests progressive values, without committing to any major form of social change.

Likewise, whilst Turnbull was once overthrown for climate change policy, it is worth recalling his comments at the time.

Turnbull exclaimed in the face of a Liberal revolt that, “We cannot be seen as a party of climate sceptics, of do-nothings on climate change. That is absolutely fatal.”

That framing matters. At the time, it appeared that the Australian public was firmly sold on climate change action, and any party that failed to embrace the new consensus would be left behind. Howard’s obstinacy on the issue helped pave the way for the election of Kevin Rudd in 2007.

Turnbull responded with what seemed to many the politically prudent position of negotiating a watered down version of Rudd’s plan on climate change action.

It was to be grossly inadequate – it committed to no more than cuts of 5 per cent of emissions below 2000 by 2020.

Ultimately, when Abbott became the new leader, he started to shift the parameters of the debate. When Rudd decided to defer pursuing an emissions trading scheme, it was a flip-flop that he had previously announced would be “absolute political cowardice”. The attack on public opinion from both sides of the political spectrum played a major role in destroying public faith in the urgency of political action on climate change.

At the time, Turnbull’s view that the Liberals should be seen to act on climate change was somewhat reasonable. Abbott’s gambit of fiercely opposing action on climate change was seen by many as a risky, if not foolish venture, and there were certainly many pundits who thought so at the time. Paul Kelly observed in the Australian in May 2009 that opposing Rudd’s emissions trading policy would be “political suicide” for the Liberals.

Turnbull’s position was less a matter of brave conviction, and more poorly executed political manoeuvring. How poorly has been exaggerated by the wisdom of hindsight: Turnbull lost the leadership of the party by one vote.

Turnbull balanced his position on climate change by lurching to the right with attacks on asylum seekers. In April 2009, Turnbull warned that Australia had become a “soft target” by Rudd’s reforms to Howard’s policies, whilst “The object of Australia's border protection policies should be no boats.”

Abbott later finessed this into a three-word slogan.

In April 2009, the US embassy observed that Turnbull “doesn't appear comfortable pursuing this issue, but is way behind in the polls and needs an issue to try to erode Rudd's formidable poll numbers”.

Turnbull naturally followed this formula. He announced in October 2009 that Rudd has “lost control of our borders”, with the arrival of a new “people smuggling boat with illegal immigrants”. Those with short memories might have forgotten that Abbott (or even Turnbull for that matter) didn’t introduce the custom of referring to asylum seekers as illegal.

By November, Turnbull was favouring the reintroduction of Temporary Protection Visas and offshore processing. Even if such policy announcements and rhetoric did make him uncomfortable, Turnbull was still willing to ride roughshod over asylum seekers in 2009 on his path to power.

His previous advocacy on a Republic, gay marriage and climate change was unorthodox within the Liberal Party. Where might he go on these positions?

On climate change, Turnbull spent almost six years in the political wilderness of the Liberals for having supported a climate change policy that didn’t have enough support within the Party. Turnbull would have to be either extremely idealistic, or very foolish, to be overthrown a second time for doing the same thing again.

To the best of my knowledge, there is little evidence that Turnbull is either of those things. Any position Turnbull takes on climate change will be very carefully attuned to the majority position of the Liberals. And the Liberals, at this point in time, are not enthusiasts for serious action on climate change.

Whilst Turnbull was once concerned that the Liberals be seen to take action on the issue, that will no longer be his primary concern.

Indeed, the rebuke and overthrow of Turnbull for his position on climate change can be seen as the lesson to him in his second run as leader. Turnbull will rule at the pleasure of the Party, and is thus on a form of probation. This was confirmed the day after Turnbull’s ascension to power.

Dennis Jensen explained to Fairfax that, “Malcolm, I think, learned some very significant lessons from 2009. Quite frankly he's not a stupid man at all, and you'd have to be pretty foolish to try the same thing twice”. Turnbull reportedly promised his colleagues that greenhouse gas emissions targets wouldn’t’ change. He also wouldn’t change the party line on gay marriage. In his first appearance in question time, he explained that “The government's policy on climate is right and it is being proved right.”

Back in December 2009, Turnbull very persuasively argued, in a prescient critique of the “direct action” policy unveiled in early 2010, that “any suggestion that you can dramatically cut emissions without any cost is, to use a favourite term of Mr Abbott, ‘bullshit’… Any policy that is announced will simply be a con, an environmental figleaf to cover a determination to do nothing.”

Turnbull explained that “the fact is that Tony and the people who put him in his job do not want to do anything about climate change.” Turnbull is now beholden to those same people, and is now defending the very con he understands as well as anyone will cement Australia’s substantial part in ensuring global climate catastrophe.

In his first press conference after overthrowing Abbott, Turnbull was asked about his policies on climate change and gay marriage. He said that he supported the policy on climate change prepared by Greg Hunt and Julie Bishop, which he “supported today” just as he did as a minister. The “climate policy is one that has been very well designed. It was a very, very good piece of work.”

He didn’t directly respond on the gay marriage issue, but has since offered his opposition to Coalition policy of a plebiscite on the issue.

Reactions

A final metric for understanding how Turnbull might rule is by looking at the response to his rise by various interested parties.

Elements within the party appear to have leaked against him already. These enemies, presumably loyal to Abbott, were more or less predictable.

Extremist anti-Muslim groups have reacted angrily to the overthrow of Abbott. One such fanatic complained about the dangers of the “far left wing prick Malcolm Turnbull”, for praising Islam. Turnbull indeed has spoken with great comfort about the historical contributions of Islamic scholars to Western science and learning, even whilst saying that Australia should support “moderate” forms of Islam.

Another group wrote, “Make no mistake Abbott was thrown out because of his stand against Islam”. Which was revealing at least of how Abbott was perceived by such groups.

Similarly, Muslim leaders quoted in the Guardian reacted with cautious optimism to the rise of Turnbull. This seemed mostly a function of Abbott’s record of “demonising the Muslim community”.

Jewish organisations were thrilled by Turnbull’s promotion. ECAJ, the leading representative body, wrote: “Throughout his public life, Malcolm Turnbull has been a consistent and outspoken supporter of the Jewish community and Israel.” He “has been a regular and welcome visitor and speaker at Jewish community functions, generous with his time and deeply supportive of all aspects of Jewish communal life. He has a thorough understanding of the Jewish community and of Israel, which he visited in 2005, and an excellent relationship with the ECAJ.”

They also warmly praised Abbott, singling out his “unerring support of Israel”, and supposedly strengthening “the security of all Australians”. The Zionist Federation of Australia also expressed its excitement, observing that they welcomed “Mr Turnbull as keynote speaker at its Plenary Assembly held in Sydney just last month.”

AIJAC, the leading private lobby of the Jewish community, observed “Malcolm Turnbull is an exceptional friend of the Jewish community and a staunch supporter of Israel. We are thrilled” and so on.

Business was also very excited by the rise of Turnbull. For example, Fairfax reported: “Oh, the joy! The business lobby could not shout its approval loudly enough on Tuesday as Malcolm Turnbull took the nation's reins as Prime Minister.” This was because “so much of what many of them would like to see had been taken off the table under the leadership of Tony Abbott. Either that, or it had sunk into a negotiated standstill through Abbott's crash-or-crash-through political style.” They thought Turnbull might be able to push through their favoured measures. One such measure he’s flagged is supporting reforms to laws which currently operate to prevent media monopolies, such as preventing a company from “owning a radio station, a tv station and a newspaper in the same market.”

Turnbull began his public march to being Prime Minister by saying that “the only way, we can ensure that we remain a high wage, generous social welfare net, first-world society is if we have outstanding economic leadership, if we have strong business confidence.”

This seems to suggest we can keep high minimum wages and a generous social welfare net by supporting the interests of big business. And if there isn’t business confidence, these might be put on the table. However, as WorkChoices and Joe Hockey’s first budget have shown, these are areas where Liberal governments must tread lightly.

One final reaction worth noting: the anger of the right-wing media types. Radio announcers like Ray Hadley and Alan Jones are very angry.

These are the relatively low-brow conservatives who Abbott cultivated and was close to. They are not fans of Turnbull.

Andrew Bolt claimed that Turnbull may not listen to people “he thinks aren’t quite as smart as he is”, and Jones quoted a young person who told him, “I could never vote for Malcolm Turnbull. He just thinks he's too good for me.” Resentment of Turnbull’s wealth and intellect are likely to play a continued role in political opponents painting him as an elitist.

As for the Murdoch press, their right-wing pundits are not fans of Turnbull either, and he has not been shy in returning hostility. He responded to a column by Andrew Bolt by claiming its speculation “borders on the demented”, was “crazy”, and “quite unhinged”.

When launching the Saturday Paper, Turnbull announced that its publisher Morrie Schwartz was “not some demented plutocrat pouring more and more money into a loss making venture that is just going to peddle your opinions.” Turnbull later claimed that these remarks were actually about William Hearst.

Yet one should not exaggerate the rift too much. Rupert Murdoch was indeed always close to Abbott, and mourned the toppling of a “decent man”. He appears to have rallied behind Turnbull to beat the ALP.

Turnbull may have previously regarded the Murdoch press as a somewhat captive media – if they don’t back the Coalition, who will they support? Yet the Murdoch press may well be able to turn away many of the Coalition’s voters from Turnbull.

I suspect one of Turnbull’s priorities may be mending fences with conservative elements of the media. Otherwise, Turnbull has generally managed to receive relatively favourable coverage from the Monthly and in the ABC and Fairfax more generally.

Trajectory

These reactions may not be an infallible guide to Turnbull’s impending reign. But they give some indication of continuities and differences. A sober review of some of the available record suggests that there is not much reason for leftists to be optimistic. There may be changes in rhetoric, but basically the same things are being sold.

Turnbull is one of the wealthiest politicians in Australia, from perhaps the wealthiest suburb in Australia, in a very wealthy electorate, with a background working in an executive role at Goldman Sachs in Australia, after being one of the most powerful lawyers in Australia. He wielded extraordinary power before politics, working closely with some of the most rich and powerful men in Australia.

Turnbull is likely to represent well the interests of the rich and powerful, who will ultimately serve as his base. The business lobby is excited, and they have good reason to be.

Turnbull has displayed small ‘l’ liberal sympathies on occasion. Yet his stances on these issues have been somewhat cautious, on relatively safe political issues. He most famously supported being seen to take action on climate change when even the Australian observed that failing to do so looked like “political suicide”.

At the same time, he was turning viciously on asylum seekers, because he thought that would help him gain political traction.

Some may find political ideals here. A more plausible reading would be some liberal instincts, tempered by the same ruthlessness he showed in his business dealings in the 80’s and 90’s.

Turnbull’s commitment to liberal values was outweighed by his commitment to pursuing power when he led the Opposition: it is hard to imagine much will change now.

On issues of style, Turnbull is likely to want to avoid the egregious anti-Muslim bigotry and dog-whistling of the Abbott government.

On policy issues, he is likely to tread cautiously in changing foreign policy or so-called anti-terrorism laws. He might want to water down some of the more egregious drafts by Attorney-General George Brandis though. Yet the Coalition will be tempted to complain that the ALP is too soft on issues of national security, and not alarmist enough about the threat of terrorism.

If the need arises, Turnbull may eventually use this stick to beat the ALP.

As for Israel, I don’t predict much change. Turnbull might struggle to be more supportive of the Israeli government than Abbott was. He’ll be wary of our expanded war on Daesh, but will probably still be determined to show our support for the alliance with America, so on that new front, I doubt we’ll be withdrawing anytime soon.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.