There was a funny moment yesterday in Parliament, when cameras caught Julie Bishop rolling her eyes while Joe Hockey was speaking. Later she put her head in her hands.

What was Australia’s Foreign Minister reacting to? It might have been reports that surfaced yesterday morning that the Expenditure Review Committee – the government’s notorious razor gang – had recommended yet more cuts to the foreign aid budget.

You could be forgiven for feeling a little sympathy for Bishop. She had just returned from Vanuatu, where Cyclone Pam had wreaked a trail of destruction across the island chain. And yet no-one had bothered to inform her of these latest cuts to her foreign aid budget, a key item in any foreign minister’s toolkit.

The rather pointed gestures from the foreign minister highlighted ongoing tensions in the federal cabinet. The government’s best performing minister by some margin, Bishop has constantly surpassed expectations since taking office. The contrast with Hockey, whose performance in the key role of Treasurer has been dismal, is stark.

There is considerable injustice, then, in the fact that Bishop’s portfolio has time and again been asked to carry the bulk of the pain of Joe Hockey’s faltering efforts at budget repair. Of course, Bishop is only the responsible minister. The true victims of the foreign aid austerity are the poorest and neediest people in Australia’s region – precisely those who most deserve our support.

Australian voters have a somewhat ambivalent attitude to foreign aid. If you ask them which part of the budget should be slashed to help consolidate the deficit, foreign aid typically tops the list. Populist sentiment often reflects the old saw of charity beginning at home. Maverick Tasmanian Senator Jacqui Lambie has been a vocal critic of the foreign aid budget, preferring to see such largesse expended in her own impoverished island home.

But foreign aid can sometimes be popular. When disaster strikes, Australians can be remarkably generous – as our warm-hearted response to the 2004 tsunami showed. Already, we’ve seen a beneficent response to Vanuatu’s devastation.

The real problem for foreign aid is that it has no strong lobby group or noisy affected industry to complain when funding is cut. Governments have responded by making foreign aid their first port of call whenever spending cuts are mentioned.

The rot set in under Labor. Kevin Rudd began his government with bold plans to lift Australia’s foreign aid spending to 0.5 per cent of our gross national income, in line with the UN’s Millennium Development Goals that we’d signed up for. By the time Julia Gillard became prime minister, the 0.5 per cent target was a distant dream, and foreign aid became a huge target for a government desperate to claim a balanced budget.

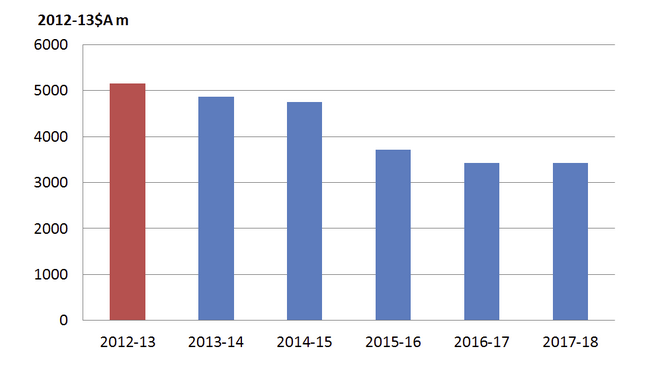

Joe Hockey continued the trend. In fact, he cut even deeper. $7.6 billion deeper. More than a fifth of all the 2014 budget savings came from foreign aid.

In December 2014, Hockey did it again. The Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook cut a further $3.7 billion from foreign aid. On some analyses, that takes Australia’s foreign aid down to its lowest level since 1954.

The upshot is that Australia is in danger of becoming a Scrooge. As we get richer, we are getting more miserly. Our economy continues to grow, meaning we are wealthier than ever. But our generosity seems to be declining in direct opposition to our wealth.

As the ANU’s Stephen Howes and Jonathan Pryke noted back in December, the cuts will play havoc with existing aid programs. “How do you cut another quarter from an already-pruned aid program?” they ask. “The aid program that emerges from the resulting slash-and-burn will be a very different beast.”

It already is.

The abolition of AusAID in 2013 was welcomed by many in the aid sector, arguing that the organisation had a mixed record and was often inefficient in its use of government funding. Unfortunately, the big cuts since have made it impossible to judge whether the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade is handling its new responsibilities any better. An environment where bureaucrats are scrambling to work out how to slash $1 billion from a $5 billion in just six months is hardly a recipe for good governance.

Figures like this should give us all pause for thought. Australia faces significant challenges in our region in future decades, and we won’t improve our chances of managing them by slashing aid to the less developed countries in our neighbourhood.

When governments fall and states fail, the cost of responding rapidly outstrips anything we spend in aid. One recent estimate put the total cost of Australia’s RAMSI intervention in the Solomon Islands at $2.6 billion. Prevention is always cheaper than cure.

The nightmare scenario is the disintegration of Papua New Guinea, our nearest neighbour and a country with massive development and governance challenges. Yet in recent times Australian relations with PNG have been focused on entirely selfish motivations, like the need to secure a jail site for seaborne asylum seekers.

As the Lowy Institute’s Jenny Haywood-Jones wrote in her assessment of the RAMSI intervention, “even if Australia does not make another large-scale intervention in the Pacific Islands region, the need of Papua New Guinea and Pacific Island countries for external assistance for a variety of governance, economic and security challenges is unlikely to disappear.”

But you won’t hear much about Australia’s regional future in the current debate on budget priorities. The ABC yesterday framed the story as a personal tiff between Bishop and Hockey, essentially ignoring the policy angle altogether.

By coincidence, Vietnamese Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung was in Canberra yesterday, appearing alongside Tony Abbott in a media conference. Someone at least asked Abbott about Australia’s foreign aid cuts, forcing Abbott to admit that, yes, they had happened.

When asked about Australia’s foreign aid cuts, Prime Minister Dung remained silent. Perhaps he thought the less said, the better.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.