A few days ago a British newspaper published photos showing Nigella Lawson being allegedly choked by her husband, Charles Saatchi. The photos have exploded online and the story of Saatchi’s apparent abuse has become headline news around the world.

Unfortunately mainstream media has a less than perfect track record when it comes to covering the issue of violence against women – particularly intimate partner violence. Recent research published by VicHealth shows that Victorian newspapers tend to sensationalise men’s violence against women, fail to link individual incidents to the ongoing systemic problem of gender-based violence, often don’t use appropriate sources, and often include details which suggest that the victim is in some way responsible (or partially responsible) for the violence. So how has coverage of the violence against Nigella Lawson fared? Here are some of the lowlights of coverage thus far.

Sensationalism

According to VicHealth research, Australian newspaper articles about violence against women are often sensationalistic, and studies in the UK have found similar results. As both Nigella Lawson and Charles Saatchi are celebrities, and there is photographic evidence of what appears to be violence, this story is particularly susceptible to sensationalistic treatment.

|

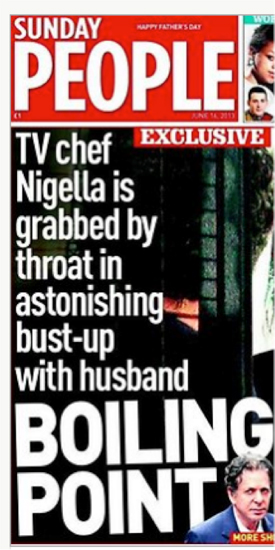

Headlines like the one above (which appears as a Facebook recommendation on the Mirror website) demonstrate how the images are used to entice readers to web content in ways reminiscent of “shocking” images of celebrity bodies (such as suggestions of anorexia, weight gain, botched plastic surgeries, and so on).

According to the editors' code of practice there was no intrusion of privacy (as administered by the UK’s Press Complaints Commission). However, the pictures do raise some issues that are worth considering. Is it possible that the publicaton of these photos without Lawson’s consent might be compounding the pain and humiliation represented in the photos?

We don’t know her perspective on this – she’s remained silent to date. Nevertheless, judging from the media response to the photos, there is some consensus that what is represented appears to be violence, and therefore it stands to reason that the continued reproduction of these images could be causing Lawson additional pain; particularly considering the tendency to publish the photos sensationalistically.

Who is responsible?

Looking again at the VicHealth research, nearly 20 per cent of articles covering violence against women include details which could imply that the victim is (at least partially) responsible for enabling the violence. One implicit way in which a victim can be posited as partially responsible is by subtly shifting the blame onto the couple, rather than the person who was violent.

Case in point: the headline of the original Sunday People article. The language here diminishes Saatchi’s responsibility, and makes it seem as though Lawson was an equal participant in the violent “bust-up”. In addition to this, the use of the term “boiling point” reproduces the myth that domestic violence occurs as a result of an individual “snapping” (i.e. reaching a “boiling point”). Domestic violence tends to be experienced regularly and systematically – not as a random one-off incident where their partner simply “snapped”.

|

Myths surrounding domestic violence continue with this unfortunate use of neighbourhood gossip as a source. The Daily Mail quotes a neighbour:

“They’re both characters and if they did this I’m sure they made up straight away as I’ve seen them together looking happily [sic]recently… They argue in the streets and are volatile at times but that could just be their form of passion.”

In addition to representing both parties as equally responsible for the violence (“if they did this”), this quote reproduces the damaging idea that intimate partner violence can be a form of extreme passionate romance. This mythology also reinforces the notion that women in abusive relationships are complicit (and possibly enjoy this violent “passion”) because otherwise they would leave. This persistent idea ignores the realities that can make it difficult for women to leave abusive partners, such as the fact that women are at 75 per cent greater risk of being killed by an abusive partner when leaving.

Numerous articles have sought explanations for the violence. Strangely they don’t look at why he might be violent, instead they consider how Nigella Lawson’s character could explain what happened. For example in the Mirror an acquaintance says that:

“She wouldn’t like to do anything to upset him. Nigella is in awe of him and surprisingly lacking in confidence herself.”

Or maybe it could be her past?

“Ms Lawson, the daughter of the former chancellor Nigel Lawson, now Lord Lawson of Blaby, has previously spoken about how she was physically abused by her mother as a child, describing how she never felt she could please her. She said her complicated childhood meant she was ‘driven by fear’ and had developed a relentless need to please people” (Daily Mail),

These quotes focus on the victim in seeking explanations for the violence rather than the person who allegedly acted violently. These narratives shift (at least some of) the responsibility for what happened onto Nigella Lawson. An exception to this is a piece by Alecia Simmonds in Daily Life which takes the opposite (and in my view correct) approach of looking to Saatchi's character for explanations.

“A clue may be found in his execrable memoir: Be The Worst You Can Be: Life’s Too Long For Patience and Virtue. Here he said that wives ‘make excellent housekeepers’ because ‘they always keep the house’. One of the obvious things that we can conclude from this is that Charles Saatchi is a misogynistic Neanderthal with a penchant for tautology. But beyond that, it suggests what criminological studies have long found: gender inequality lies at the root of domestic violence.”

This piece is also commendable for noting that the underlying causes of violence against women include a belief in rigid gender roles and weak support for gender equality. As VicHealth research has shown, the most common predictor of the use of violence among men is their agreement with sexist, patriarchal, and or sexually hostile attitudes.

Calling it gender-based violence

Among the key findings of the VicHealth research into media coverage of violence against women is the tendency for media to individualise discussion of gender-based violence. This means that reporting rarely links the incident of violence with the serious social problem which affects one in three women in Australia, and 70 per cent of women worldwide. In Australia, almost every week a women is killed by a partner or ex-partner. And for those out there that object because women can be violent too, it’s important to note that research shows that, 82 per cent of those physically assaulted, and 99 per cent of those sexually assaulted, were assaulted by a male.

In terms of language it’s important when discussing violence against women that terminology doesn’t minimise the gravity of the problem.

“There has never been any hint of any marital issues…” (Herald Sun).

Terms such as “marital issues” reinforce the idea that domestic violence is a couple’s private problem, and not a serious systemic social issue. Thankfully, the term “domestic violence” is being used relatively often in mainstream coverage of the violence shown in the photos. However, there remains a tendency to individualise the problem. Narratives that focus on Lawson's lack of self-confidence offer nothing informative about the dynamics or prevalence of intimate partner violence. And, apart from a few exceptions like the one noted above, the link between gender equity and violence against women is nearly invisible in the mainstream coverage.

As disturbing and problematic as these photos are, they do challenge us to consider the wider societal problem of violence against women. Unfortunately, the misrepresentation of the issue of domestic violence in mainstream media perpetuates ignorance and myths. Only by challenging these myths can society truly address this serious and ongoing social problem.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.