DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Australia has built one of the greatest social systems in the world, but we have a major blind spot when it comes to employment, writes Albert Zhou. It wasn’t always like that.

Australia – the lucky country. We’re one of the richest countries in the world. In fact, this year in 2018 we ranked first, as the country with the highest median wealth per adult. We enjoy many comforts that other countries do not enjoy – electricity, running water, a welfare system, subsidised university education and student loans, and free health-care.

Yet despite our wealth, and despite our wonderful society, many people still fall through the gaps. Automation of factory and other jobs, structural economic changes like globalisation, becoming older, and sometimes just plain bad luck can leave people without a job for years.

Prolonged involuntary unemployment is not only stressful and takes a toll on one’s mental well-being, but it’s also a huge waste of human capital. Many hard-working and skilled potential employees are prevented from making a positive contribution to society because of external economic circumstances.

A Job Guarantee is one potential way of redressing the economic injustice. It’s a program in which the government would guarantee access to work for all citizens; and would also harness unused labour to engage in community and sustainability projects; projects which would otherwise not be undertaken for their lack of monetary return.

A recent report by not-for-profit think tank PerCapita and the Australian Unemployed Workers’ Union investigates the nature of long-term unemployment today, as well as presenting the associated challenges. As one might expect, it is much more difficult to find a job for older workers – the average length of time searching for work for people over 55 was 68 weeks. But even young, educated people can face difficulties.

The report presents Oliver, a 36-year-old with a Bachelor of Business, who having been made redundant in 2016, suddenly found himself unemployed for the next two years. Another example is Sarah, a 24-year-old who was unable to find any full-time work after graduating from her degree in 2015. The average length of time for those aged 15-21 to find work is 30 weeks, while for those aged 25-54, it is 49 weeks.

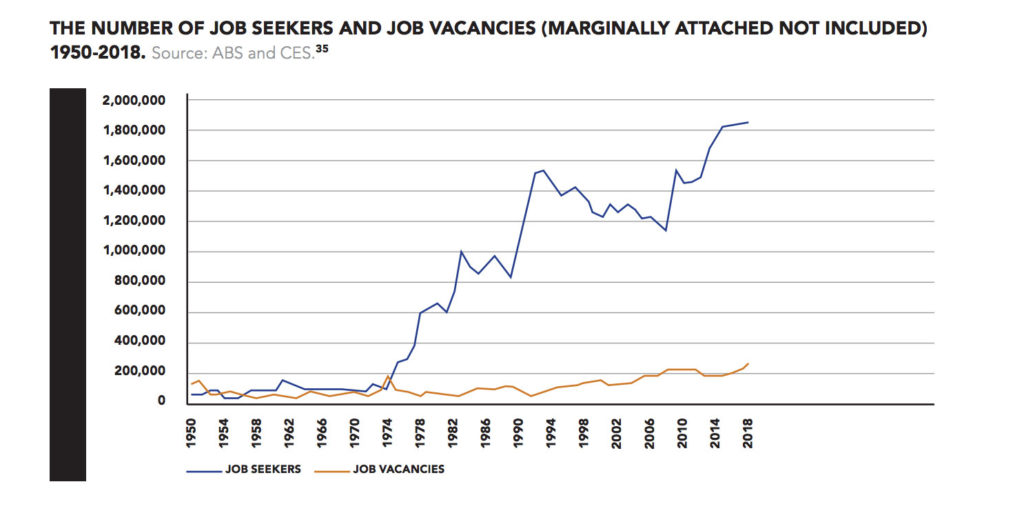

Why is it that such a broad spectrum of Australian society is having difficulty finding work? The answer is purely numerical. The number of job seekers vastly exceeds the number of job vacancies, currently at a ratio of 15 job seekers to each job. And this has been the case ever since 1974 (see graph below). But prior to 1974, there was a job vacancy for pretty much every job seeker.

So what changed?

Before 1974, there was bipartisan support for the policy of full employment: to try to employ everyone looking for a job in society. To this end, the Commonwealth Employment Services was established to provide assistance for those looking for a job, as well as financial support for migration and training. While it existed, it maintained unemployment at an average level of less than 2% (compared to around 5% today) and the average duration of unemployment was seven weeks. But in 1974 the full-employment policy was dropped (because of the oil crisis) and focus turned to managing inflation; employment became the responsibility of the individual.

The result was that by the end of 1975, there were six times as many people looking for work as there were job vacancies.

There’s no reason for millions of Australians to be left without a job, in many cases for years, just because the private sector is unwilling to employ the number of able and willing workers available.

A Job Guarantee could address the growing problem of involuntary unemployment by providing jobs for the unemployed. The jobs would be generated by local governments, charities and registered not-for-profits. Such a program would be funded by the Federal Government, and its size would be adjusted to reflect the left-over demand for jobs. The program would not be capped, but fluctuate based on need, just like our healthcare, education and income support systems.

The program would be flexible to allow local communities to address their own needs, and develop themselves autonomously, whilst also allowing jobs to be tailored to employees’ skills. Participants of the program would be paid the full minimum wage, and also be given the benefits of full-time employment – like sick leave and holiday leave.

The consequences of such a program would be significant. Care, cultural, environmental and charitable work could be monetarily remunerated. By empowering local communities to decide their own needs, it allows people to decide what work is profitable, and what work is not – rather than the market deciding what is useful, profitable and productive. It would also be a huge opportunity to address and mitigate the looming global environmental disaster, by coordinating people seeking work to contribute to the greatest moral, social and economic challenge in history.

For example, in their 10 years of operation between 1933 and 1942, the Citizens Conservation Corps (a full-employment program created to get America out of the Great Depression) planted a total of 3.5 billion trees as part of land care.

A Jobs Guarantee would also address the injustice of our inept, privatised employment-services provider jobactive, and the support systems which are failing the unemployed. These were designed in the 1970s, when full employment of the populace was pursued by governments, and so it was possible for every potential worker to find a job.

Nowadays, they are not only failing to help the unemployed, but also needlessly punishing them. In principle, jobactive exists to help the unemployed find work; but in practice it acts merely as an agency to enforce the compliance of welfare recipients with rules dictated by Centrelink.

Failure to comply results in penalties on recipients, with the aforementioned report stating that since the inception of jobactive in July 2015, 5.2 million penalties have been imposed.

The penalties, however, have a high rate of error, with 50% of penalties being wrongly applied in the 2015-16 financial year. That means close to a million unemployed workers were penalised that year despite having done nothing wrong.

Part of the problem is that jobactive collects fees from the Government when it fulfils certain requirements; requirements which are not in the interests of those they are meant to be helping: the unemployed.

What it costs

The net cost of a Job Guarantee is estimated to be $22 billion annually. To put that in perspective, the income tax cuts the LNP Government passed will cost an average $14 billion a year; and their dumped corporate tax cuts would have cost an around $8 billion per year. Add those two numbers together, and you have the income for a Job Guarantee.

GetUp, a community advocacy group, has been campaigning for the trial of a Job Guarantee, and I’m hopeful that such a trial will take place.

We Australians think everyone should have a fair go. It’s why we subsidise university education and health care. We guarantee these things for everyone, because if not, the demand for good health and education would be so high that the prices of these things would exclude average Australians from their benefits. Why do we not do the same thing for jobs?

With expected further automation of industry, other technological disruptions of the labour market, as well as an ageing population, there are going to be tough times ahead for many people. With many job-seekers and few jobs, bargaining power is put in the hands of employers, and many people are then excluded from the labour market or open to exploitation.

There are already three million people (13.2%) living below the relative poverty line ($433 a week for a single adult), including 739,000 children (17.3%), and many of these living in “deep poverty” ($298 per week for a single adult).

It is vital that we, as a country and as a society, pursue the goal of employment for everyone, otherwise, things will get a lot worse for a lot of people.

Author’s note: thanks to Milo from GetUp! for his feedback and help with research.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.