DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Australia’s commitments to tackle climate change at home are already not being met, but the situation is even more dire when you look at what Australian companies are doing overseas. Richard Hil weighs in.

Are the lives of US citizens worth more than, say, those in Africa? It depends on which populations we’re talking about. But if reports on the recent US floods in Missouri and Kansas and the cyclone in southern Africa are anything to go by, then the answer is a resounding yes.

That, at least, is the conclusion you might draw after glancing at the 22nd March edition of the Sydney Morning Herald which devoted a two-page spread to the catastrophic flooding in the US which, at that stage, had resulted in the loss of five lives and widespread destruction, while less than two inches of space were allotted to the climate-related tragedy in Africa, the effects of which are still unfolding.

In many ways, this disproportionate coverage reflects the routinized nature of western reporting on the impacts of climate change. Indeed, there’s a long and shameful tradition of ignoring or downplaying disasters in the global south, as if the lives and property of “our own” take precedence over all others, and that what occurs in distant lands has nothing to do with us.

Long suffering Africa

According to a Global Carbon Project report presented in 2018 to the international climate conference in Katowice, Poland, carbon emissions for that year were at record levels. Some nations, of course, are far more responsible than others for this situation, with the US and increasingly, China and India, leading the pack.

In contrast, Africa is responsible for about 4 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions. As noted by the US Department of Energy, Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Centre: “Africa’s fossil-fuel CO2 emissions are low in both absolute and per capita terms. Total emissions for Africa have increased twelve-fold since 1950… still less than the emissions for some single nations including Mainland China, the US, India, Russia, and Japan. [P]er capita emissions were still only 6.6% of the comparable value for North America…. A small number of nations are largely responsible for the African emissions from fossil fuels and cement production…. Only four African countries have per capita CO2 emissions higher than the global average.”

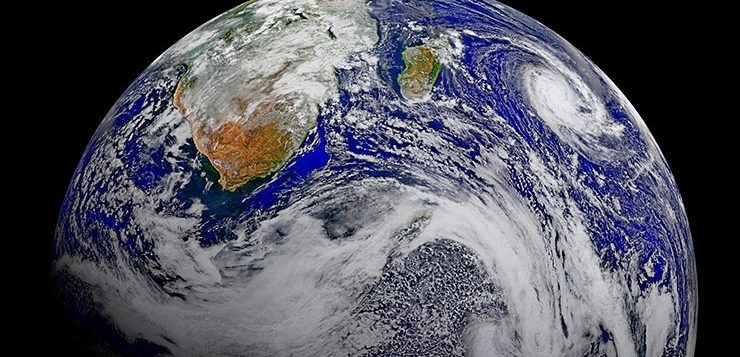

Despite its relatively modest contribution to carbon pollution, Africa – the poorest continent on the planet with 383 million people in extreme poverty – suffers disproportionately from the effects of toxic emissions from wealthier nations. The impacts of this are felt most acutely by the poor and marginalised, with extreme weather events occurring more frequently and with greater ferocity.

To compound this already alarming situation, the western media has tended to attribute much of Africa’s (and the global south’s) problems to cronyism and internal corruption, rarely if ever acknowledging the impact of colonisation and incursions by western corporations, aid agencies and other entities.

The historical antecedents that explain the current plight of so-called developing countries are often swept under the carpet, as the wretched of the earth are rendered the unpeople of global geopolitics, without a voice and often subject to the humiliations of powerful nations.

None of this is to suggest the absence of deep-seated, systemic problems in the governance of poorer nations. Corruption and cronyism are indeed endemic in many of these countries. But the full explanatory account of the west’s role in such situations is invariably missing, with Venezuela being the latest case in which a beleaguered nation finds itself under the most severe threat from western interests and propaganda.

Idai’s path of devastation

A category two system, tropical cyclone, Idai packed winds of 175 kph that impacted large parts of Mozambique before carving a destructive path through Malawi and Zimbabwe. Nearly three million people were affected, and the Mozambique city of Beira – a low-lying coastal metropolis – was virtually destroyed, with around half a million residents having to flee their homes.

Current estimates of the dead and injured vary, but the figures could run into the thousands, with the threat of cholera likely to increase the death toll, making this among the most lethal of storms in the southern hemisphere.

The effects of the cyclone were amplified by preceding rains that saturated the land, making the cyclonic deluge even more disastrous, including a storm surge (estimated at 4 metres) that caused widespread flooding and inundation.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, as of 23 March, around 90,000 people were languishing in overcrowded shelters across the region. Additionally, thousands of schools have been inundated and over 33,000 houses destroyed, along with 50,000 hectares of crops, making food scarcity a growing threat.

Women have been especially impacted by these events, with many having to take care of their families, thereby diverting them from life-sustaining agricultural work, and thousands of pregnant women facing increased risk of disease.

Clearly, the situation facing the people in this part of southern Africa is grim. As of 26 March, James Elder, Regional Chief of Communication for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa, observed, “Right now I am on the ground in Mozambique where entire villages have been submerged, buildings flattened, and schools and health care centres destroyed by Cyclone Idai. Amid it all, children’s lives have been turned upside down. Hundreds of thousands are at risk from waterborne diseases. Others are simply lost….”

Climate scientists agree that the warming of the planet, its air and oceans, has meant more rainfall, tropical cyclones and hurricanes, and other extreme events. Mozambique is particularly prone to the ravages of extreme weather, with droughts, flooding and inundation occurring more regularly.

Meanwhile, on the ground in Beria, as a result of crop damage, food prices have risen sharply, and supermarkets, warehouses, and storage facilities have been destroyed, thereby making access to food supplies very difficult. This situation has been exacerbated by damage to roads and bridges, making transportation of food and medical supplies almost impossible.

Given that life is already tough in these southern African nations – Mozambique and Malawi figure among the world’s poorest nations – the impact of the cyclone will only make matters worse. It may be tempting to attribute these events to Africa itself, especially to the growing number of mining projects that are increasing the continent’s (still comparatively modest) contribution to the global climate emergency. And yet, closer inspection of investment in African mining reveals a telling tale of western involvement in these projects.

Writing in The Guardian on 21 March, shortly after the cyclone struck southern Africa, Landry Ninteretse, lead spokesperson for 350.org in Africa, observed that: “While many countries appear to be already reducing carbon emissions and moving towards an energy transition, Africa’s coalfields are open for business. Along with a few Asian countries (Indonesia, Vietnam and Bangladesh in particular), our continent continues to be an El Dorado for the coal cheerleaders and big business determined to carry on its coal-onisation.”

Ninteretse notes that new coal plants are planned in a number of African countries, including Mozambique. “Most of them”, she observes, “are co-financed by the African Development Bank, on whose board sit members of African, European, North and South American and Asian governments”.

Australia has huge investments in Africa too. Drawing on data from Australia-Africa Minerals and Energy Group, Eryk Bagshaw writing in the Sydney Morning Herald (September 10, 2017), notes that as of 2017, “Australia will become the biggest international miner on the African continent, doubling its investment to more than $40 billion over a decade”.

One hundred and forty Australian companies operate mining projects across Africa, says Bagshaw, citing data from tax transparency network, Publish What You Pay Australia. Huge amounts of coal are to be extracted: up to 34 billion tonnes worth, “more than three times that of Adani’s proposed Carmichael mine in Queensland”.

According to campaigning organisation, Action Aid, this huge overseas venture runs against the grain of Australia’s supposed commitment to the Paris agreements by adding millions of tonnes of carbon atmospheric pollution. Other concerns identified by Bagshaw, included the impact of mining on small communities, numerous mining accidents, tax avoidance and unscrupulous business practices, bordering on corruption.

Much of this is outside the purview of the Australian public, yet the profiteering of many of Australia’s leading mining companies at the cost of the environment raises significant questions.

Paying the price

Oil extraction also attracts huge investment, according to Landry Ninteretse, with multinational companies like Total, Shell, Exxon, BP and Eni gaining a significant foothold in this lucrative market. Buoyed by the prospect of cheap labour and high returns, Africa is seen as a grand money-making venture, along with other operations around the world, many in some of the poorest nations on Earth.

For Africa, the impacts of increasing global carbon emissions has been and remains devastating. As Ninteretse writes: “For us [in Africa], climate change is not a future risk, it’s already a reality evident in wrecked families, lands and livelihoods, and hopeless children and young people who have no choice but to seek a future by migrating. Everywhere on the continent, communities fear losing their land as each season hits one country after another with exceptional floods, unexpected storms and increasingly long droughts. Fauna and flora reserves have been running out, access to water has become a privilege, and extreme weather events have become more numerous and left families without homes or livelihoods.”

The argument that more adaptation funds can assist African nations to cope with the ravages of climate change is, says Ninteretse, “an insult to people facing untold suffering in every corner of the continent, while new coal and mining infrastructure and carbon commodification continue to be allowed.”

In addition to the cessation of fossil fuel extractivism, and a wholesale shift to renewables, Ninteretse calls for “African countries… to step up efforts against environmental degradation and greenhouse gas emissions, for instance, by decentralising energy supply systems, and by promoting tax policies that favour solar and wind energy investments.” She further asserts that African nations must do more to protect their own people from the ravages of climate change – both in terms of mitigation and adaptation, and they must hold fossil fuel companies to account for the damage inflicted on people and the environment as a result of “decades of unregulated exploitation of coal, oil and gas”.

Ninteretse calls for international activist organisations to continue to pressure governments and corporations to make the urgent changes needed to avoid global catastrophe.

The brutal consequence of cyclone Idai is another stark reminder that millions of lives depend on concerted global action to address the climate emergency, although it may well be too late.

Australia, like many other rich western nations, bears considerable responsibility for this situation and its impact on the world’s poorest people. Two inches of reportage in a state-based newspaper really doesn’t do the crisis in southern Africa justice.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.