It’s 2023 – four decades since Bob Hawke won office, introduced Medicare, and then corrupted his own creation. And yet despite overwhelming scientific and medical consensus of the harm it causes children, Australia still subsidises male circumcision, writes Chris Coughran.

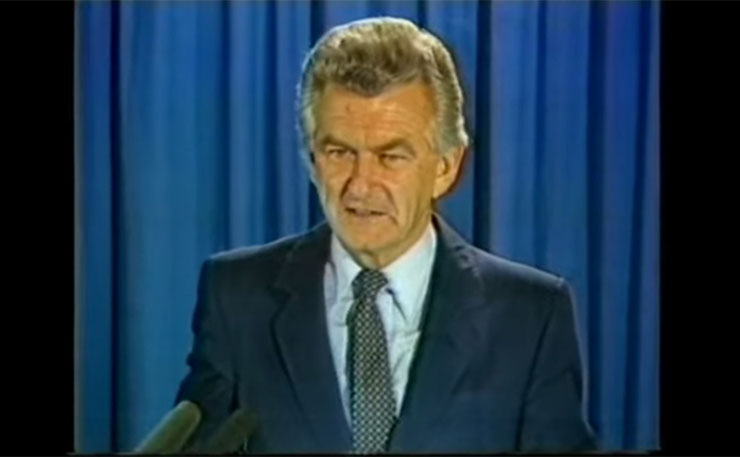

“Every Australian, from newborn babe to prime minister, can share in the cheapest, simplest, and fairest health insurance scheme Australia’s ever had,” Bob Hawke boasted in 1984. But by July of the following year, Hawke was personally intervening in health department affairs in order to create loopholes in the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS).

The issue was neonatal circumcision, and its planned removal from the MBS on 1 July 1985. Such a swift policy excision had been the legally, ethically, medically, and fiscally responsible course of action recommended to health minister Neal Blewett by the Australian College of Paediatrics, the National Health and Medical Research Council, and the MBS Revision Committee.

Although widely applauded, the decision did not go down well with people of the book, especially the Jewish community in Melbourne.

Blewett recalls Hawke telephoning to berate him for signing off on this particular aspect of Medicare reform: “You’ve united the Jews and the Moslems for the first time in a thousand years, and against us.”

“If it’s good enough for me it’s good enough for the MBS,” Hawke would summarily conclude correspondence with a senior health department official seeking advice on the matter from the prime minister’s office.

“I’m an Israeli,” Hawke had proclaimed to Blanche d’Alpuget two years earlier. “If I were to have my life again, I would want to be born a Jew.” Throughout the 1970s, as leader of the Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), Hawke had visited Israel on several occasions, befriending the likes of Golda Meir, Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres.

Honorary Jewishness was effectively conferred in 1976, when “a forest of 10,000 trees on the southern side of Mount Carmel in northern Israel was named in Hawke’s honour.” Hawke was deeply moved by the gesture, but—according to Hawke’s most recent biographer, Troy Bramston:

“Rawdon Dalrymple, Australia’s ambassador to Israel from 1973 to 1975, revealed that Israeli leaders cultivated Hawke. “They regarded Bob as a bit naive,” he said. “They saw him as someone who is not a fool but swallows a line.” This view is backed up by a dispatch sent from the British High Commission to London after Hawke became prime minister. “Hawke seems to me to have been the archetypal sucker upon who the Israelis are always ready to seize, and to con, feeding uncritical minds with skilful Israeli propaganda,” John Mason wrote.”

At home, Hawke’s philosemitism was proudly on display, much to the consternation of Australian Labor Party (ALP) stalwarts including rival leader Bill Hayden. Hawke’s growing reputation as “a genuine legend” among the Australian Jewry fuelled speculation:

“… that Melbourne’s Jewish community had established a fund for Hawke to ensure that he had whatever he needed to make the transition into parliament. It was referred to as a political “nest egg.” He could use it for travel, accommodation and meeting policy experts.”

Hawke’s philosemitism, Bramston says, was “fostered by friendships he developed in the Melbourne business community.” It was also psychologically driven, by Hawke’s need of “atonement for past sins”.

Melbourne businessman Isi Leibler recalls Hawke confiding to him that he had once “engaged in an anti-Semitic act that nauseated him to such an extent that he was determined to compensate for [it]by showing his friendship to Jews.” Specifically, Hawke had once used antisemitic language and “beat up a Jewish boy.”

The confessional nature of such a disclosure betokens deep familiarity and trust. According to the influential Leibler, his friendship with Hawke was “extremely warm on both personal and political grounds”.

Indeed, Leibler had been the catalyst for Hawke’s ACTU missions in the early 1970s to negotiate freedoms on behalf of Russian Jews detained in the Soviet Union (so-called “refuseniks”). For almost 20 years Leibler would serve as president of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry.

According to Bramston, Leibler was also inaugural chairman, in 1978, of the ACTU–Jetset Travel Service, a successful public–private partnership that delivered not only $1 million per annum in travel discounts to trade union members but also “a regular stream of revenue to the ACTU”.

Capitulation to religious interests dealt a significant blow to the integrity of the MBS, almost from its inception. The Hawke government’s backflip on male circumcision, as Robert Darby suggests, has had a chilling effect on Medicare reform, with dire consequences for the health and human rights of Australian children.

Non-therapeutic circumcision procedures — and even the emergency repair of botched ones (separate MBS item) — continue to cost Medicare millions of dollars per annum. Medicare data even reveals a significant proportion of female “circumcision of the penis” rebate claimants.

Was Hawke corrupt? Perhaps no more so than any other Australian political leader. In politics, as in patriarchal religion, sacrifices must be made. In 1996, under John Howard’s conservative coalition prime ministership, “senior federal government figures” reportedly “stopped a plan to remove circumcision from Medicare” in order to mollify “the wealthy Jewish community and the conservative Christian churches”.

Within today’s ALP government, the cult of Hawke looms large, and Medicare — even when ravaged by crisis — remains the illustrious former leader’s signature policy, revered as “totemic” and “sacrosanct” among the party faithful.

Providers of non-therapeutic neonatal circumcision services, meanwhile, continue to advertise the Medicare rebate on websites and street signage, immune from discipline or censure, much less prosecution.

Declaration: The author is a survivor of a botched, government-funded, neonatal (eighth-day) circumcision procedure.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.