ESSAY | By Chris Graham

Ask yourself this: how many women do you know who’ve been sexually assaulted? Now ask yourself how many men you know who’ve admitted to sexual assault, let alone been jailed for it? Now try and explain that gap. The fact is, Australia’s legal and political system is in crisis, and not just because a former High Court judge turned Royal Commissioner appointed to the role by a Prime Minister world famous for his misogyny turned out to be a serial sexual harasser of women, and had to face a second independent inquiry ordered by an Attorney General now facing allegations of rape. The system is in crisis because the system is the problem, writes Chris Graham.

Politics is all about perspective, and depending on yours, 1988 was either an auspicious year for Australia, or a disaster. Auspicious, because it marked the bi-centenary of the arrival of the British. Disaster, because it marked 200 years since… the arrival of the British. For Kate, one of the figures at the centre of a growing political storm in Australia over violence against women, there was never any doubt what 1988 represented.

By all accounts, during her early years Kate was a vibrant, outgoing, intelligent girl. A champion debater, friends described her as the person they most believed might one day become Australia’s first female Prime Minister.

Even as a teenager, Kate was already moving in influential circles. In 1986, at age 15, she represented South Australia in the annual Rostrum Voice of Youth national public speaking championships. A student at the prestigious St Peter’s Collegiate Girls School in Adelaide, Kate came second in the junior division. The boy who beat her was Andrew O’Keefe, then a student at Sydney’s elite St Ignatius College, Riverview.

Of course, back then, neither Kate nor O’Keefe could be sure of the direction their lives might head, but violence against women would very much become a theme for both of them.

O’Keefe is the son of Supreme Court Justice Barry O’Keefe and the nephew of rock legend Johnny O’Keefe. He would, of course, go on to carve out a successful career as a lawyer, then as a star for Channel 7, earning himself an Order of Australia along the way for his charity work. O’Keefe’s fall from grace earlier this year, amid allegations he assaulted his partner, was made all the more spectacular by the fact he’d served both as a Chairman and ambassador for the White Ribbon Foundation, and on the National Council for the Prevention of Violence Against Women.

But back to Kate. Two years after her loss to O’Keefe, Kate once again represented South Australia in the Rostrum competition, this time as a senior. And once again, she came second. Elise Elliott, who would go on to a successful career as a Channel 9 journalist, a job that would see her assaulted by a man in 2011 while working on a ‘story’ for A Current Affair, came third. That competition was in July 1988, but the event which would forever change the course of Kate’s life had, Kate alleges, already occurred.

Six months earlier, on January 10, and just 16 days before the nation stopped to celebrate its bi-centenary – largely oblivious to the wholesale rape, slaughter and dispossession of a whole continent of people that preceded it – Kate, six weeks shy of her 17th birthday, was in Sydney to represent Australia in an international debating competition.

Late that evening, after drinks at an official function, Kate alleges she was violently raped by team-mate Christian Porter, a boy from Perth one year her senior. The assault allegedly occurred at the University of Sydney’s Women’s College dormitory, an infamous building that former Sydney criminal barrister Charles Waterstreet – himself a serial sexual harasser of women and Australia’s first official #metoo ‘victim’ – once waxed lyrical about, with some affection.

USYD’s women’s officer Anna Hush writes in 2017:

“Reflecting on his time at John’s in The Age, [Waterstreet] wrote: ‘When men are gathered together in living quarters as boys, when their hormones are raging against the night, fuelled by Foster’s and unlimited liquor, in an atmosphere that winks at shows of bravado and rebellion, then the consequences are predictable. Someone is bound to go too far because the boundaries are so blurred.’

Ah, those familiar blurred lines. For what else is a boy to do, when his hormones are raging and the beer is freely flowing?

In his memoir, [Waterstreet] writes jovially about spying on nurses at the adjacent hospital as they undressed after their shifts (calling it “a vital part of a fresher’s duty”). Waterstreet also fondly recalls having “kissed the bottom of every girl at Women’s [College], running from room to room flinging the bedclothes off and lifting their nightdresses up and plastering a wet one”.

Of course, Waterstreet’s fond memories of the good old days, when men could sexually assault women without sanction, doesn’t, by virtue of association or location, mean Christian Porter is also a sex offender, a fact Porter would know, given he also went on to a successful career in law, then politics. Until last month, Porter served in one of the highest political offices in the country, and the highest legal one – the office of Attorney General, the first law officer of the Crown.

Kate, by contrast, is dead.

“I believe women are just as corruptible by power as men, because you know what, fellas, you don’t have a monopoly on the human condition, you arrogant fucks. But the story is as you have told it. Power belongs to you. And if you can’t handle criticism, take a joke, or deal with your own tension without violence, you have to wonder if you are up to the task of being in charge.”

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

Better days, and years

FAST forward three decades to 2020, a year which, unlike 1988, didn’t get mixed reviews. Pretty much everyone agrees 2020 was a train wreck, courtesy of a global pandemic that has paralysed economies and killed almost 3 million people, and counting.

From Kate’s perspective, however, and from the perspective of the family and friends who loved her, 2020 was something even more than a train wreck. In February, Kate contacted NSW Police to discuss filing a criminal complaint against Porter for the assault she alleges occurred 32 years earlier.

Police had been intending to travel to Adelaide to formally interview her. COVID-19 put a stop to that. Four months later, on June 24, one day after ringing police to tell them that she was no longer intending to pursue the matter, Kate, then aged 49, died in her Adelaide home. She was reported to have taken her own life, although at the time of press, the SA coroner is still considering whether or not to conduct an inquiry.

Kate was farewelled at a small, private funeral on July 3. A day later, The Age carried a tribute from Kate’s family and friends, which ended with this quote from Shakespeare’s Macbeth.

“…the innocent sleep,

Sleep that knits up the

ravell’d sleave of care,

The death of each day’s life,

sore labour’s bath,

Balm of hurt minds,

great nature’s second course,

Chief nourisher in life’s feast…”

The verse describes how innocent people sleep well. But its broader context is Macbeth describing how he never will, because his conscience was wracked with guilt over his involvement in the murder of King Duncan.

Nine months later, Christian Porter fronted media to strenuously deny the allegations that Kate, from the grave, had levelled against him. Gaunt and clearly deeply distressed, Porter asked media to consider, even just for a minute, that the allegations might not be true. With the support of his party and prime minister, Porter also announced he would not be resigning from his job as Attorney General, and he dismissed calls for an independent inquiry, arguing they would undermine the very laws he’d sworn to protect and uphold.

With that, Porter walked out of the press conference, and shortly after, Parliament House. He’s been on paid leave ever since. But the allegations from Kate aren’t going anywhere. They’re still sending shockwaves around the nation, and showing no signs of weakening.

Do you know what should be the target of our jokes at the moment? Our obsession with reputation. We’re obsessed. We think reputation is more important than anything else, including humanity.

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

Taking the good with the bad

2020 was a much better year for Scott Morrison, although it wasn’t for lack of trying. After disappearing overseas for a family holiday to Hawaii in late 2019, he hurried back to seething public outrage over his gross mishandling of an unprecedented bushfire emergency that was literally engulfing the nation. The details of Morrison’s bungling are now the stuff of legend. But as the flames died down, Morrison lurched to a new disaster when news broke that $100 million of taxpayer money had been illegally targetted to Coalition-held electorates to bolster the government’s chances in the run-up to the May 2019 election.

We might all have still been talking about the ‘Sports Rorts Affair’ today if not for the COVID-19 pandemic. When a crisis of pandemic magnitude hits, not much else matters. But either way, Morrison started 2020 as a desperately unpopular Prime Minister, and he ended it with the sort of political support most leaders don’t even dare dream about. So all up, 2020 turned out to be a pretty good for year for Morrison, although it obviously didn’t go as planned.

In January 2019, Morrison had announced $50 million to fund 2020 celebrations marking 250 years since Captain James Cook ‘discovered’ Australia. As the Member for Cook – literally, Cook, named after the Captain – the appearance of a conflict of interest might have shamed other politicians into a more modest funding announcement. But there was an election in the wind and Morrison has never seen a marketing opportunity he didn’t try and exploit, particularly not if someone else was paying for it.

“As the 250th anniversary nears we want to help Australians better understand Captain Cook’s historic voyage and its legacy for exploration, science and reconciliation,” the Prime Minister said. The emphasis is mine, but I swear, he literally said that.

‘History’ and ‘facts’ apparently not being Morrison’s strong suit perhaps explains why his funding package included the circumnavigation of the country by a replica of Cook’s Endeavour: “From Far North Queensland and the Cooktown 2020 Festival across to Bunbury and down to Hobart, our Government will ensure Australians young and old can see firsthand the legacy of Captain Cook and the voyage of the Endeavour.”

Of course, the Endeavour never sailed anywhere near Tasmania, nor the west coast. As it turned out, Morrison’s replica didn’t either – the celebrations were cancelled, another casualty of COVID-19.

As the May 2019 election drew nearer, Morrison was also keen to spruik his party’s credentials on the protection of women and children. A media release six weeks after his Cook announcement boasts of “record funding to reduce domestic violence”, including almost $70 million for an advertising campaign to “counter the culture of disrespect towards women”. Morrison claimed that “combating violence against women and children” was one of the “top priorities” of his government.

“All women and children have the right to feel safe, and to feel supported to seek help when they need it,” the release noted. It might be hard to accept that a government’s ‘top priority’ gets $70 million for an advertising campaign, while a party to celebrate something deeply divisive that happened 250 years ago gets $50 million, but regardless, it’s worth noting the date of Morrison’s announcement on funding to tackle violence against women: it was March 5, 2019.

A fortnight later, Liberal staffer Brittany Higgins, then aged 24, was allegedly raped in a ministerial office less than 50 metres from Morrison’s. It’s also worth noting that Ms Higgins didn’t feel very “supported” by the Morrison Government when she told them about it, a fact she disclosed to media last month which prompted her former boss, then Defence Minister Linda Reynolds, to describe her as a “lying cow”.

Higgins’ story, of course, is a key part of how we got here today. Amid growing national outrage at her treatment, details of the allegations against Porter, which had been sent to three politicians by an anonymous friend of Kate’s, leaked out. The background is important to this story, because without Higgins’ courage – she’s taking on the entire federal government, the most powerful institution in the nation – then Kate’s story might never have seen the light of day.

ABC Four Corner’s reporter Louise Milligan is the journalist who broke the story of the anonymous letter, but it’s not the first time Milligan has aired allegations about Porter’s conduct towards women. Milligan was also the author of a Four Corner’s investigation broadcast in November 2020, entitled ‘Inside the Canberra Bubble’.

The story alleged that apart from a history of misogynistic public statements – which Porter admits – he nearly blew his chance at the Attorney General’s job after being spotted ‘kissing and cuddling’ a junior Liberal staffer at a bar in Canberra, just weeks before then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull was expected to elevate him to the position.

Milligan had also been planning to report the allegations levelled against Porter by Kate, but that part of the story was pulled amid concerns from Kate’s family.

Regardless, the day after the remainder of the story broke, Porter publicly denied the allegations on radio 6PR in Perth. You can read the full transcript of Porter’s interview – and his slippery denials – here. After you do, you might also want to contemplate if it’s a public contribution befitting a man who considers himself suitable for the position of Attorney General.

Louise Milligan was also the journalist behind a story that aired on Four Corners this month, a follow-up to the November expose, entitled ‘Bursting the Canberra Bubble’. One of the key people quoted in the story is, unarguably, one of the brightest legal minds in the country and, for some at least, a voice of calm and reason in the face of rising public rage.

Arthur Moses SC was the president of the NSW Bar Association when multiple complaints of sexual harassment were brought against Charles Waterstreet. Those complaints – now three years old – have never been finalised, although that’s another story for another day. There’s no suggestion Moses was personally responsible for the delay – his term expired in 2018 – but there’s also no denying he is a major political and legal player, both in NSW and on the national stage.

Moses is a respected part of the legal establishment, and his defence of Australia’s criminal justice system, in the 4 Corners story above, and beyond, is worth exploring, because it represents not only the main argument against a probe into Porter’s conduct, but also the key defence more broadly of Australia’s ‘rule of law’.

“Some of my colleagues who are calling for an inquiry are some of my closest friends and colleagues who I’ve served with either as predecessors of the law council or in other areas, and I respect them immensely, but I disagree with them profoundly on this issue,” Moses told Milligan.

“In my view, you cannot call for an inquiry into whether a criminal offense is allegedly being committed in a situation where the criminal justice system has determined that there is no charge to be laid in respect of the matter, because what you’re then doing is adopting a shifting sands approach to our criminal justice system.

“If you determined who was to be the subject of an inquiry based on who they are and based on what the alleged crime is, that is not how we operate within this country and I think it takes us down a very worrying road as to what may happen in the future.”

To paraphrase Moses, I don’t know him, but I do respect him. But on this, I profoundly disagree. The problem here is not that we might take a ‘shifting sands’ approach to a foundational principle of the criminal justice system. The problem here is the criminal justice system itself, and in particular, how it deals with allegations of sexual assault. The evidence of that is undeniable, but before we delve into the cold, hard facts, it’s worth trying to connect with the problem in a way that might help you better understand it from the perspective of the people most harmed by it. Women.

“I am not a man-hater, but I am afraid of men. If I’m the only woman in a room full of men I am afraid, and if you think that’s unusual you’re not speaking to the women in your life.”

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

Getting there

One of the things I respect most about people like Arthur Moses SC – and many others who work within the criminal justice system – is their capacity to stay focussed and professional. If you’ve spent any time in an Australian court, it’s full of stories of the worst moments of peoples’ lives. Against that backdrop, I can understand the importance of ‘keeping the faith’, and dispassionately discharging your duties with a higher goal in mind, no matter how distressing the things that come before you. But that principle only works well in a system that works well.

Lucia Osborne-Crowley is an Australian journalist, essayist, writer, and legal researcher. She’s also a rape survivor, having been brutally assaulted by a stranger at knifepoint in 2007. In 2018, she wrote, “It is harder to bear witness to suffering than it is to analyse it, and until we are ready to do that, real change will evade us. You have to live through things before you can understand them. You can’t always take the analytical position.”

A tiny fraction of men are ever likely to live through the things that Osborne-Crowley has, and for that we should be grateful. But that also means a significant proportion of the population is left with, as Osborne-Crowley explains, an ‘analytical position’ on the sort of event that almost defies description. So how do we connect in a way that helps us better understand, without paralysing us?

A couple of simple questions might help.

Firstly, ask yourself how many women in your life have told you they’ve been sexually assaulted. Now, ask yourself how many men in your life have admitted to sexually assaulting a woman, let alone been jailed for it?

The gap, I’m guessing, is enormous, but the problem of explaining away that gap is even bigger. Either women overwhelmingly lie about sexual assault, or men overwhelmingly lie about committing it. And for the record, multiple studies suggest that of the rapes that are actually reported to authorities (and it’s less than 10 per cent), as little as two per cent of those turn out to be false.

Of course, there’s one other statistically theoretical possibility: a tiny proportion of men commit the overwhelming majority of sexual assaults. Quite apart from the fact that the opposite is true (87 per cent of women know the person who assaulted them) even if it were a small number of men committing all of the assaults, that’s still a resounding condemnation of our justice system. Because if it’s such a small number of offenders, why can’t the system find, prosecute and jail them?

You might argue – and defenders of the justice system do – that securing a conviction for sexual assault is extremely difficult specifically because it lessens the risk that innocent people will go to jail. That may be true – and we’ll explore that theme later in this essay – but it’s also not an explanation for why the system fails so badly, it’s simply a justification for why that failure should continue. It’s also a likely explanation for why sexual assault is so prevalent… because perpetrators know they’re unlikely to ever be held to account. We’ll come back to that as well.

The truth is, almost one in five women aged over 15 in Australia today report having survived at least one sexual assault in their lifetime. And yet at the same time, a tiny fraction of men have been convicted for sexual assault. No matter how you spin it, we have some ugly truths to face about the realities of violence against women in our society. One of those ugly truths is that it’s not a tiny percentage of men at all. It’s the men we know. And they’re assaulting the women we love. That should infuriate you… and we haven’t even gotten deep into the data yet.

“What I would have done to have heard a story like mine. Not for blame. Not for reputation, not for money, not for power. But to feel less alone. To feel connected. I want my story heard.”

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

The awful truth

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), in 2019 police across the nation recorded 26,892 cases of sexual assault. Of those survivors, 22,337 (83 per cent) were female. As for the perpetrators, the profile of the person most likely to commit rape in Australia is a male, aged 15-19. That’s right, teenage boys are the most prevalent rapists in our society. You can obviously guess who they’re raping, but just in case you can’t, here’s a statement from the ABS from 2016: “Females aged between 15 and 19 years were seven times more likely to have been a victim of sexual assault compared to the overall population.”

Unfortunately, the ABS doesn’t publish the data which tells us how many of those reported assaults resulted in a prosecution, let alone a conviction, because the process nationally of collecting that data is notoriously shambolic. I should add, that’s not entirely the fault of the ABS, it’s because there’s no national standard. That should tell you something about where ‘violence against women’ ranks as a national priority, both to the Morrison government and every administration before it.

Fortunately, NSW does make its data available, courtesy of the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR). In 2019, NSW police recorded 4,444 sexual assaults against people aged over 15. In the same year, 1,015 cases resulted in court proceedings. Of those, 667 resulted in a verdict of guilty, and of those, 257 resulted in a custodial sentence.

To put that in plain English, of the assaults that came to the attention of NSW police in 2019, just over 5 per cent of them resulted in someone going to jail.

That figure, while shocking in its own right, is also grossly misleading, because it only takes into account the sexual assaults that came to the notice of police. The actual number of assaults is considerably higher – about 10 times, in fact. In 2016, for example, an estimated 201,000 adults were sexually assaulted, while police recorded 23,040 incidents.

If you commit murder in Australia, there’s an almost 90 percent chance you’ll be caught. But we already know that the overwhelming majority of sexual assaults won’t even be reported to police, let alone end up in a jail sentence. From the publicly available data, including the ABS’s Personal Safety Survey 2016, we can calculate roughly what your chances were of being jailed if you committed a sexual assault in NSW in 2019.

A conservative estimate is 0.7 per cent. Or put another way, on average you could commit about 150 sexual assaults – one a week for almost three years – before you might expect to be sent to jail for one of them. And the average sentence you can expect for that rape is about two years and two months.

By contrast, the odds that the survivors of those assaults will be cross-examined by a defence lawyer who’ll be seeking to prove that either their behaviour, demeanour, past sexual history, clothing and/or level of intoxication at the time of the assault contributed directly to the attack are 100 per cent. That’s what happened to a close friend of mine, who put her faith in the criminal justice system, only to watch the accused walk free.

I asked her recently how any woman could trust a system that so routinely and comprehensively fails them: “When you go to court, not only do you have to get past the fact that you feel vulnerable, shameful about your own rape, but you’re entering into a process that tells you it’s your fault, aggressively accuses you of lying and you’ve got to prove you’re telling the truth.

“As the cross examination was happening, I was thinking, ‘Why is he asking me so many question’s about my skirt? I didn’t ask for this’.

“It was humiliating, and I had to do it twice, once in front of a magistrates court, and then again in front of a jury.

“It goes beyond the system failing you. The system itself is damaging. It just adds to the trauma. It feels like a second rape.”

“I don’t tell you this so you think of me as a victim. I am not a victim. I tell you this because my story has value. I tell you this ‘cause I want you to know, I need you to know, what I know. To be rendered powerless does not destroy your humanity. Your resilience is your humanity. The only people who lose their humanity are those who believe they have the right to render another human being powerless. They are the weak. To yield and not break, that is incredible strength.”

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

An adversarial versus inquisitorial justice system

Like all offenders before a court, alleged rapists are presumed to be innocent until proven guilty. Or in the words of Arthur Moses SC on Four Corners, “Christian Porter, at the end of the day, is entitled like anybody else to the presumption of innocence and the right to silence.”

Of course, Porter is not before a court on allegations of rape, he’s just defending himself from them in the court of public opinion. Even so, few people would disagree with the broader ethic outlined by Moses. But given that defendants who have pled not guilty are presumed to be innocent until it’s found they’re not (i.e. they’re convicted), you might equally ask why is the survivor of a sexual assault not also presumed to be truthful… until it’s found they’re not?

There’s two main reasons. The first is the processes that we use. In Australia, most parts of our criminal justice system are based on what’s called an ‘adversarial system’, where a prosecutor battles it out with a defence lawyer, and a judge sits in the middle and plays referee to ensure both sides abide by the rules. If you’ve never experienced it, you might be surprised to learn that the goal of an adversarial system is not to get to the truth. It’s simply to win. The truth, if that’s where you end up, is a bonus. I’ve been round a lot of court cases in my career. I like to think of it as ‘big dick energy in silly gowns and wigs’.

The belief is that in winning (or losing), the truth comes out. Which it often doesn’t, and when it does, it’s not through lack of trying to ensure it doesn’t, as this article by Mark Shaw, an Indiana defence attorney who sat through the 1992 trial of Mike Tyson for raping 18-year-old Desiree Washington, illustrates perfectly.

The article is prefaced as a review of “the hottest legal battle of 1992”, which might equally be described as ‘a woman’s rape as entertainment’, and Shaw waxes lyrical about things Tyson’s defence team could have done differently to get their client off. Nowhere in the 3,900 word story does Shaw go anywhere near expressing anything that might even remotely be considered an interest in the truth, let alone any empathy for the survivor, Ms Washington. It’s the literal definition of ‘big dick energy’ (sans silly gowns and wigs) and while it describes a battle in a US court, the system has the same base as ours.

The other style used in Australia’s legal system is an inquisitorial one. If you’ve ever sat in a coroner’s court, that’s an inquisitorial process in action. There are no ‘winners or losers’, per se, in a coroner’s court – the simple goal of the coroner is to uncover the truth. As that process plays out, it looks to casual observers just like a normal court.

The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime describes the two systems better (and more charitably) than I can: “The inquisitorial system is… characterized by extensive pre-trial investigation and interrogations with the objective to avoid bringing an innocent person to trial. The inquisitorial process can be described as an official inquiry to ascertain the truth, whereas the adversarial system uses a competitive process between prosecution and defence to determine the facts. The inquisitorial process grants more power to the judge who oversees the process, whereas the judge in the adversarial system serves more as an arbiter between claims of the prosecution and defence.”

An inquisitorial justice system is not without its own challenges, but it certainly appears to have merit in the case of allegations of sexual assault. Not only is it a pursuit of the truth, but it can be structured to ensure an innocent person doesn’t even stand trial, let alone get convicted. That’s something even men’s rights activists can get behind.

The second and main reason why a survivor of sexual assault in an adversarial system is not ‘presumed truthful’ until proven otherwise has to do with a legal principle called ‘Blackstone’s ratio’. If you think you haven’t heard of it, you probably have: it holds that ’10 guilty persons should walk free so that one innocent person doesn’t suffer’.

The suffering is a direct reference to what might follow a guilty verdict. Australian society believes that the gravest thing we can do to punish someone for their criminality is to deprive them of their freedom. And so, if we propose to do that, the bar should be set very high. The advantage should rest with the accused, which is why the onus is on the state to prove guilt, not the accused to prove innocence.

That works well when the victim is ‘society’, or ‘the state’ – for example, when someone is convicted for drug offences, the second most common direct cause of jail time in Australia. The ‘victim’ – society – is not actually traumatised by the alleged crime (which begs the question why drug use is a crime… yet another story for another day). But it doesn’t work well when the victim is someone who has survived sexual violence, and the life-long trauma that inevitably comes with it.

I don’t think many people would disagree with the principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’, but I do wonder what thought has been given to the standards we set for how the survivors of sexual assault are treated. I wonder what compensations our criminal justice system makes for people like Kate, or my close friend, when it fails them? You might suggest their freedom was never actually at stake, but I’d suggest that any woman – any person – who’s been dragged through a criminal court proceeding and accused of lying or causing their own sexual assault probably doesn’t feel very ‘free’ at the end of the process.

Kate never saw the inside of a court, and so she wasn’t brutalised by it. But even so, I also don’t imagine she felt very ‘free’ from ages 16 to 49, when she finally died.

“The damage done to me is real and debilitating. I will never flourish.”

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

It’s not like we didn’t know

Like the conversations that have raged all over the nation around #metoo (and well before it), there have long been calls for reform of the criminal justice system in how it deals with sexual assault. Legal experts and academics have been acknowledging that elephant in the room for decades. The internet is literally saturated with academic papers, reviews, discussions, statistical analyses and story after story of failure, dating back to before the internet was even a ‘thing’. The following is just a tiny sample of them.

This report, entitled Sexual Assault in South Australia, was written in 1983: “The low rate of convictions for adults on ‘minor’ charges, and the relatively infrequent findings of guilt for lone attacks where consent could be raised as an issue, suggested that there may be room for legislative change – for example introduction of a series of offences, with penalties graded according to the degree of violence and the nature of the sexual act. Other potential areas for reform include cross-examination rules….”

The 1983 research also took a special interest in ‘rape in marriage’, which had only recently been partly criminalised in South Australia, the first jurisdiction in the English-speaking world to make it against the law for a husband to rape his wife (it took until 1994 for it to be fully outlawed in all Australian jurisdictions).

“In light of the controversy which surrounded the removal of spouse-immunity, the research gave special attention to the arrests where partners or ex-partners were accused. In all, two husbands – both living apart from their wives at the time of the alleged incident – were apprehended.

“One was accused of breaking into his wife’s home, and both were alleged to have used violence. Neither was found guilty, although one case went to trial.

“The four former husbands and two former defactos apprehended during 1980 and 1981 also had their cases dismissed or were acquitted. In fact, the entire history of the ‘rape in marriage’ legislation, since its introduction in 1976, shows that only one husband has ever been found guilty of raping his wife.”

It’s worth noting the opening lines ‘In light of the controversy which surrounded the removal of spouse-immunity….’ In other words, South Australian men had to be dragged kicking and screaming into accepting that it was no longer legal for them to rape their wives.

In 2006, Kathleen Daly and Sarah Curtis-Fawley, two criminologists from Brisbane write: “Studies of the experiences of sexual assault victims in the criminal justice process come to similar conclusions: despite decades of legal reform, the police and courts continue to fail victims.”

Here’s another 2006 report this one from the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, written by Jacqueline Fitzgerald, which looks at the ‘attrition of sexual offences from the New South Wales criminal justice system’. Fitzgerald notes: “Each year NSW Police receive reports of more than 7,000 sexual and indecent assault incidents. Only about one in ten of these incidents result in someone being found guilty in court.”

This is a paper by legal expert Kylie Weston-Scheuber presented at a justice conference in Sydney in 2011. It notes: “Low conviction rates in sexual assault prosecutions are notorious. The Australian Institute of Criminology reports that in 2006, more than 18,000 victim incidents of sexual assault and related offences were recorded across Australia by police, estimated to represent at most 30 percent of actual incidents. Less than 20 percent (<3,600) of these were estimated to result in criminal proceedings being initiated. Of those 3,600, between one quarter and one third were dismissed without hearing, with a similar proportion resulting in a plea of guilty. Of matters going to trial, about 4 in 10 defendants were found guilty, resulting in a conviction rate (pleas of guilty and findings of guilty) of about 10 percent of reported sexual assaults.”

Here’s a submission from the Northern Centre Against Sexual Assault from 2015 which outlines the calls for reform to embrace an inquisitorial system, over an adversarial one. And here’s a review from 2016 of how defence lawyers conduct themselves during sexual assault cases. It’s called, Lawyers’ Strategies for Cross-examining Rape Complainants: Have We Moved Beyond the 1950s?

The NSW Law Reform Commission in September last year stated: “Despite decades of legislative reform, sexual offences remain under-reported, under-prosecuted and under-convicted.”

It’s hard to get plainer English than that. It’s also hard not to notice that almost all the authors of these papers are women. And it’s impossible not to notice that the response of parliaments around the country over the decades has been, at best, to tinker at the edges. In NSW, for example, parliament amended the Crimes Act in 2008 to give clarity around what consent looks like in a legal context. And here’s the subsequent report from the NSW Law Reform Commission more than a decade later which describes the high farce that was the senior judiciary’s confused handling of the rape allegations levelled by 18-year-old Saxon Mullins in 2015.

And who could forget the work of the #LetUsSpeak campaign, run by Nina Funnell*, End Rape on Campus and Marque Lawyers*. So backward is Australia’s response to sexual violence that a group of survivor advocates and lawyers had to campaign to amend laws to allow survivors to speak publicly after they were sexually assaulted… followed shortly thereafter by a campaign to amend laws in Victoria which aimed to prevent the names of women killed in the course of sexual violence from ever being publicised.

But if you really want to get a sense of just how far behind the rest of the world Australian thinking is on an effective judicial response to sexual violence, consider this: the ‘adversarial versus inquisitorial’ debate has been ongoing in India for years, but the difference there is it’s now being led by the legal industry itself.

“The Bar Council of Delhi (BCD) has demanded the setting up of a separate police force and replacing the colonial system of investigation and trial with a French inquisitorial system to deal with cases of crimes against women in the country,” the Hindu Times reported in January 2020. And in case you missed it, the Bar Council of Dehli is the statutory body which oversees the conduct of lawyers in New Dehli. It’s the largest bar council in the country with more than 60,000 members. It’s equivalent in Australia is the NSW Bar Association, of which Arthur Moses SC – the Four Corners interviewee who opposes any inquiry into the allegations against Porter – is a recent past president.

The Hindu Times report continues:

“In a letter to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, BCD chairman K.C. Mittal said that though substantive legislative amendments were carried out in the Indian Penal Code following the Nirbhaya case, they had failed to reduce crime against women. ‘It is high time that the government take a call to revamp and change the system drastically.’”

The ‘Nirbhaya case’ is a reference to the 2012 gang rape of Jyoti Singh, a 23-year-old woman, on a bus in Delhi, which shocked a nation. Her injuries were so catastrophic she died from them. Four of the perpetrators were hanged last year for the crime.

That debate, about how the Indian criminal justice system should respond to sexual violence, rages on in a nation where rape within marriage is still legal, and where, earlier this month, a Supreme Court bench headed by the Chief Justice of India asked a man whether or not he was ready to ‘make an honest woman’ of the person he’s accused of raping: “Will you marry her? If you are willing to marry, we will consider this (petition)… or else you will go to jail and lose your job.” Not to mention his reputation.

That debate also rages on in a nation which a 2018 survey by the Thomson Reuters Foundation found was more dangerous than any country on earth in terms of sexual violence perpetrated against women.

So what does that say about Australia, where the debate does not rage on? For me, it says that if our criminal justice system were an old dog, you’d shoot it, which is a lot more merciful than the system has been to survivors.

I wouldn’t want to be a straight white man. Not right now. Not at this moment in history. It is not a good time to be a straight white man. I wouldn’t want to be a straight white man. Not if you paid me. Although the pay would be substantially better.

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

Safer jobs for the boys

A colleague, Nina Funnell, joked to me a few years ago (actually, half-joked is probably a more accurate description) that if men menstruated instead of women, period blood would be celebrated as a sign of masculinity, and white pants would never go out of fashion. NRL games would be monthly, not weekly, and timed to coincide with the highest number of men whose cycles aligned with each other. And of course there would never have been a GST on tampons.

Obviously, we’ll never be able to prove Funnell’s thesis, but if you want evidence that the society we’ve built today was designed primarily for the benefit of men, our justice system is a pretty good place to start. And I’m not just referring to its clear failures to effectively prosecute rape.

The history of Australia’s labour laws, and in particular the protection of workers, is long and complex. You can read a brief summary of one of the key battlegrounds – workers’ compensation – here. But in brief, prior to the 1900s, the costs of work-related injuries in Australia were borne by workers themselves. There were some modest advancements by the 1920s – new laws meant workers only had to prove their injury was work-related in order to access compensation. But things then stalled for the next half century, “due in part to the prevalence of conservative governments at both a federal and state level”. Think Sir Robert Menzies, a Liberal party hero to men like John Howard and Tony Abbott.

From the 1970s onwards things started steadily improving again. Perhaps nowhere was that more the case than in the outback NSW town of Broken Hill. The Hill, as locals call it, was named by the ‘founding fathers’ of BHP (which literally stands for Broken Hill Proprietary), who, in 1885, started mining one of the world’s biggest deposits of lead, zinc and silver. Three decades later, it was Broken Hill miners who staged the 18-month long ‘Great Strike’ of 1919-20, to win the first 35-hour week in Australia.

I’m actually writing this essay from Broken Hill, and 500 metres from my office is a memorial to the 800-plus miners who lost their lives digging up minerals for rich business owners.

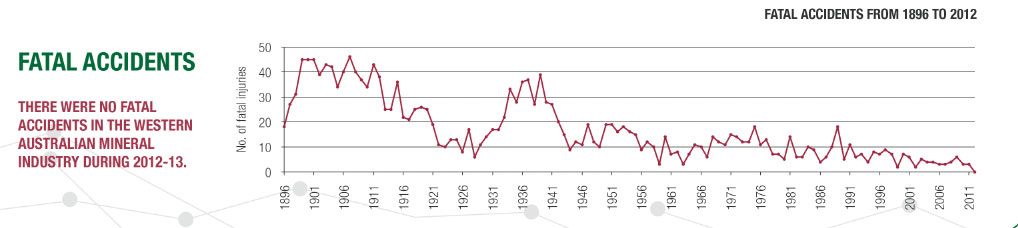

Of course, people weren’t just dying in NSW, or Broken Hill. The graph pictured below, produced by the West Australian government, charts the rise and fall in worker deaths in the WA mining industry since before Federation. In addition to deaths, workers at the turn of the 19th century were also being injured in huge numbers, and in those days, in the absence of a social welfare system, a serious work injury almost certainly led to abject poverty.

So, people with less power banded together to confront people with more power. Workers formed unions, bargained collectively, and, over time, forced governments to introduce legislation specifically designed to improve safety for workers, and provide for them and their families in the event of death or disability.

In the process, an entire ‘court system within a court system’ – an ‘industrial relations system – was created, replete with whole government agencies and departments to support it and, of course, courts. As a result, Australia today is a pretty safe place to work. In fact, just a few years ago it was ranked as the safest place on earth for workers.

In 2003, the United Nations International Labour Organisation (ILO) ranked the world’s 34 ‘Established Market Economies’ (countries whose economic growth has been a major factor in poverty reduction) on their ‘work-related mortality rate’ – that is, not only workers killed on the job, but workers whose deaths could be traced directly back to their employment.

Australia had the lowest rate in the world, at 58 ‘work-related deaths’ per 100,000 workers per year.

Today, the rate of death on the job is about half what it was in 2003, although notably the spike in the graph below, from 2005 to 2007, shows workplace deaths after John Howard introduced his WorkChoices legislation, designed to gut the power of unions and workers, while driving down wages and re-empowering employers.

But if you’re thinking that safer workplaces came about because employers felt bad about workers dying, you’d be wrong. At a certain point, the cost of keeping workers safe becomes cheaper than killing them. That’s how, over time, employers in Australia worked out that safer workplaces are more stable workplaces, and more stable workplaces are more productive workplaces. It’s always about the money, although in this case it was also about the gender.

Our industrial relations laws evolved to place greater financial and legal responsibility on employers not because too many people were dying, but because too many men were. And when too many men die, other men start losing money.

The 800-plus workers honoured on the Broken Hill memorial I mentioned above are exclusively male. Those mines opened way back in 1885, when women made up a tiny fraction of the workplace – less than 20 per cent of women were engaged in the labour force. But even today, with the advances in workplace safety, if a worker dies in Australia, there’s still a 93 per cent chance it will be a man, and that’s despite the fact today the participation rate for women in the labour force is more than 60 per cent.

The safety of men is such a big deal in Australia that an entire industry spanning both the public and private sectors has sprung up around it. Chain stores exist to sell clothing to make work (predominantly for men) safer. Corporations and small businesses exist to provide safety training. The Occupational Health and Safety Services industry in Australia today is estimated to be worth around $1.6 billion annually, a figure roughly equivalent to Australia’s global cotton export.

And so, if saving the lives of men can make other men richer, where, might you ask, are the cashed up private investors keen to fund women’s shelters? Why hasn’t an industry sprung up around the protection of women, given so many of them are dying at the hands of men? It’s not like gouging money from women trying to escape violence is too vulgar for Australia’s business elite.

The answer is because the protection of women in Australia is not a national priority, and never has been. The ‘industry’ which seeks to make women and children safer consists entirely of charities, who rely almost exclusively on government funding for their existence. And as anyone who knows anything about that ‘industry’ will tell you, there’s never enough of it to go around. Although Scott Morrison – the Member for Cook who allocated $50 million for a party to celebrate Captain Cook – obviously thinks otherwise.

And if you’re still not convinced labour laws evolved to make life safer for men, not workers, the legislation I mentioned above, which changed in the 1920s to ensure workers finally had access to compensation for work-related injuries, was finally rewritten in the 1970s to ensure “…terminology was changed to include female workers”.

To the men in the room, I speak to you now, particularly the white men, especially the straight white men. Pull your fucking socks up! How humiliating! Fashion advice from a lesbian. That’s your last joke.

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

The boys club

From January to December 2015, 33 workers died working construction in Australia. All of them were men. The same year, 31 women had already been killed by men by early April. By the end of 2015, Counting Dead Women Australia – a volunteer organisation with a Facebook page (which tells you even more about the importance of sexual violence statistics to society) – reported the female body count had climbed to 84.

That’s more than eight times greater than the number of men killed in the mining industry (10) for the same period. In fact, 84 dead women is only eight female corpses shy of the top two most dangerous industries for 2015 combined – ‘Agriculture, forestry and fishing’ (52 deaths) and ‘Transport, postal and warehousing’ (40 deaths).

The Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union (CFMMEU) – which represents 144,000 workers across four of those industries – is one of the most powerful organisations in the country. Combined with the Transport Workers Union (TWU), which boasts more than 90,000 members, the two organisations are worth about a half a billion dollars, with annual revenue in the hundreds of millions.

That’s not to suggest they don’t do a good job – they clearly do. The death rates in their respective industries have been trending downwards for years. But where are the powerful organisations worth hundreds of millions of dollars formed specifically to protect the safety and interests of women? Being a truck driver is a dangerous job, but in Australia, it’s not nearly as dangerous as being a mum, a wife, a partner, a girlfriend… or occasionally a complete stranger.

In explaining that absence, it’s helpful to recall who the Prime Minister of Australia was while the body count of those 84 women piled up. Obviously, the ‘laundry list’ of misogyny that spewed out of Tony Abbott’s mouth over the years is far too extensive to document here, but it’s worth remembering at least a few highlights.

In the 1970s while a university student (where he was accused of punching a wall on either side of a woman’s head to intimidate her, which he denies) and then later of indecently assaulting a woman (which he also denies), Abbott wrote: “I think it would be folly to expect that women will ever dominate or even approach equal representation in a large number of areas simply because their aptitudes, abilities and interests are different for physiological reasons.”

In 2002, while Abbott was a cabinet minister in the Howard Government, he suggested that women shouldn’t withhold sex from their husbands in marriage: “I think there does need to be give and take on both sides, and this idea that sex is kind of a woman’s right to absolutely withhold, just as the idea that sex is a man’s right to demand I think are both, they both need to be moderated, so to speak.” How ironic that Abbott was elected to Federal Parliament the very same year (1994) that rape within marriage was finally outlawed across Australia.

In 2010, while leader of the Liberal Party, Abbott told media: “What the housewives of Australia need to understand as they do the ironing is that if they get it done commercially it’s going to go up in price and their own power bills when they switch the iron on are going to go up.”

And let’s just pause briefly, to remember this moment in history from October 2012… then Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s now world-famous ‘misogyny speech’.

How about that time in 2013, when Abbott appointed his first cabinet as Prime Minister. It included one female (Julie Bishop), and so Abbott of course appointed himself Minister for Women.

By 2014, when 82 women died at the hands of men, Abbott decided it was finally time for a Royal Commission. But not into the number of women being slaughtered. Instead, he ordered a Royal Commission into the trade unions, apparently concerned that legislation had gone too far in protecting the safety of men. Looking at the significant dates of that Royal Commission is a lesson in just how oblivious Abbott and his colleagues have been to the violence inflicted on women, and just how ridiculous the entire system really is.

Abbott announced the Royal Commission on February 11, 2014… the same day that Sydney man Simon Gittany was sentenced to 18 years jail for throwing his fiancé, Lisa Harnum, off the balcony of their 15th floor apartment in Sydney. The judge in that case was Justice Lucy McCallum, who a few months earlier handed down a defamation ruling against Zoo Magazine for photoshopping Senator Sarah Hanson-Young’s face onto a lingerie model. Hanson-Young, of course, was one of the recipients of the anonymous letter detailing Kate’s allegations against Christian Porter. The very day Kate’s story broke, Hanson-Young won an appeal against a second successful defamation action, this time against former parliamentary colleague, David Leyonhelm, who falsely claimed Hanson-Young described ‘all men as rapists’.

The terms of reference for Abbott’s Royal Commission were signed off a month later, on March 13, 2014… the same day Sydney man, Farden Fazah, was sentenced to 20 years jail for stabbing his wife 12 times, and then murdering his two-year-old daughter. That killing didn’t get as much press coverage as it otherwise might have, because Australian media were transfixed by the trial of South African athlete Oscar Pistorius, who’d just vomited in court at the site of photographs of the woman he murdered, his girlfriend Reeva Steenkamp.

The Royal Commission finally reported almost two years after it began, on December 29, 2015… the same day news broke that Queensland’s Director of Public Prosecutions, Michael Byrne QC was planning to appeal a decision to downgrade the murder conviction of Gerard Bayden-Clay to manslaughter. Bayden-Clay murdered his wife, Allison, then dumped her body on a riverbank in Brisbane in 2012. She left behind three young children.

As for the man Tony Abbott appointed to oversee the Royal Commission, it was Dyson Heydon. An independent investigation launched by the High Court of Australia last year found he was a serial sexual harasser of women.

The same day that the results of the High Court investigation were released, the Sydney Morning Herald detailed further allegations against Heydon. Six days after that, the Morrison government bowed to growing pressure and ordered the Attorney General’s Department to conduct a fresh investigation into the new allegations. The man who ordered that investigation was Christian Porter, a man now facing allegations of rape.

Turns out there is a place for independent inquiries and ‘trial by media’ after all. Just so long as it’s not happening to you.

“There is no way anyone would dare test their strength out on me, because you all know, there is nothing stronger than a broken woman who has rebuilt herself.”

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

Keeping the faith

It’s one thing to have faith in the institutions that underpin our society. But when one of those institutions – or at least a significant part of it – isn’t working and we won’t even consider discussing changing it, that’s not faith, that’s blind faith, and blind faith is how you sustain a religion, not a criminal justice system.

It’s ironic when you think about it, because a few hundred years ago or so, it was the Catholic Church that made most of the laws that governed our lives. The reason why it doesn’t anymore is because ‘the system’ didn’t protect enough of the people it claimed to serve. It protected the elites – men, the only people allowed then (and still now) to hold high office in the Church. And that is precisely what we’re confronting today – a growing body of people, in this case women, who are railing against a system that is failing them. Spectacularly.

Speaking of failure, and keeping the faith… if you think Scott Morrison’s handling of the growing scandal that is engulfing his government is going to improve, then you’ve already forgotten how his 2020 started.

Under pressure, Scott Morrison doesn’t just crumble, he is his own walking disaster zone, which is the reason why it appears to follow him everywhere. Morrison’s problem is his default – his instincts on this issue are mired in deep ignorance, evidenced by his apparent epiphany that what happened to Brittany Higgins was bad… because his wife told him so. No amount of empathy training is going to fix a default so out of whack.

I don’t have a crystal ball, but I don’t see how Morrison can lead his party back into government, despite the massive boost he received over his government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. Like our legal system, our political system may be broken, but even at its lowest, a government led by a man of so little substance cannot, surely, be sustained.

Morrison navigated the pandemic comparatively well because, for one of the few occasions in recent political memory, a federal government was actually guided entirely by science on a major political issue. It’s worth remembering, that as the bushfire crisis raged, Morrison & Co pointedly refused to acknowledge its links to climate change, and their policies since look identical to their policies prior. It’s also worth understanding why governments around the country adopted an evidenced-based approach on COVID-19: they won’t be around to be held accountable for their failures on mitigating the effects of climate change. A pandemic, however, lends itself to much more rapid political critique. By the same token, historically. the rape of a young liberal staffer 50 metres from the Prime Minister’s office hasn’t, although times appear to be changing.

But just as cataloguing Tony Abbott’s misogyny would take too long here, so too would cataloguing Morrison’s mishandling of this issue. So the totality of his response – and its deep hypocrisy – is perhaps best summed up by lawyer Michael Bradley*, who was acting for Kate when she died.

Scott "there is only one law, there is no other law" Morrison, the man who demanded the Aust Post CEO resign for failing the pub test.

— marquelawyers (@marquelawyers) March 11, 2021

In case you missed it, the ‘Aust Post CEO’ was a woman. Christine Holgate, who was forced out of her job after she was accused by her enemies of providing overly generous bonuses to high performing staff, in particular four senior staff who each received a gold Cartier watch (total value, less than $20,000). Whether or not you think that sort of largesse is appropriate, it’s hard to make a case that Holgate should go, but someone like, say, the Member for Bowman, Andrew Laming – an upskirter of women – should stay.

And while I still don’t have a crystal ball, expect Laming to announce his resignation from the Liberal Party sometime soon, whereupon he’ll slink to the backbench and wait out the storm. Laming can’t resign his seat – and Morrison won’t ask him to – because it would trigger a by-election, and a by-election would trigger another Morrison-esque crisis that would likely result in the seat returning to Labor, and a wafer-thin majority in the House of Reps being reduced even further.

Long story short, our government and parliament is in crisis, and no amount of ‘smoke and mirrors’ from Morrison appears sufficient to stop the tail-spin in which the Prime Minister now finds himself. Even issues that should be uncontroversial are blowing up in his face.

Over the past few months, calls have been growing for a Royal Commission into the number of suicides of current and ex-service men and women. Parliament has already backed a motion to establish an inquiry, and Morrison – keen to distract – indicated he would no longer oppose it. He’s not supporting it, but he says he’s not standing in the way either.

Enter Liberal Senator Jim Molan, a former Major-General with the sort of communication skills you might expect from… a former Major-General. He snatched intense focus from the jaws of distraction by suggesting a Royal Commission shouldn’t go ahead because the mother of a dead veteran who has been leading the push is apparently ‘disingenuous’ and ‘duplicitous’.

As to the actual merits of a Royal Commission, from Morrison’s perspective all they do is highlight his failures elsewhere: an article in The Conversation recently was headlined: “One veteran on average dies by suicide every 2 weeks. This is what a royal commission needs to look at”. That’s half the rate at which women are dying at the hands of men, by the way.

In September last year, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare reported: “From 2001 to 2017, there were 419 suicides in serving, reserve and ex-serving Australian Defence Force (ADF) personnel who have served since 2001. Compared with Australian men, the age-adjusted rate of suicide over this period was 48% lower for men serving and in the reserves, and 18% higher for ex-serving men.”

The number of women who died at the hands of violent men was 50 percent higher, in half the time.

Almost as a footnote, the AIHW report adds: “Over the same period, the age-adjusted rate of suicide among ex-serving women was higher than that of Australian women.” The actual figure is never reported.

I’m not suggesting there shouldn’t be an inquiry into the suicides of men and women who served their country. There clearly should be. But I do wonder why Parliament isn’t also talking about a Royal Commission into violence against women, although it’s definitely not because of a lack of money. Tony Abbott’s Royal Commission into the unions cost $45 million. That’s $5 million less than Scott Morrison was prepared to spend on a party to celebrate one man, after whom Morrison’s electorate was named, and who died two centuries earlier.

And it’s definitely not because a Royal Commission might result in a ‘poor conviction rate’. Abbott’s inquiry saw a handful of people prosecuted. At the same time, today, at least three sitting MPs – Christian Porter, Andrew Laming and Michael Johnsen – face allegations of sexual violence against women, and a fourth, former Labor minister Milton Orkopoulos, was sent back to prison for child sex offences. That occurred on the very day the storm erupted over the alleged rape of Brittany Higgins.

“To the men in the room, who feel I may have been persecuting you this evening… well spotted. That’s pretty much what I’ve done there. But this is theatre, fellas. I’ve given you an hour, a taste. I have lived a life”.

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

Not the end

I’m not an expert in the law, and this essay, which seeks to make a case for reform of the criminal justice system in its handling of sexual assault, has been written from that perspective. I don’t claim to know what the solution to prosecuting sexual assault looks like either. But I do know what it doesn’t look like… what we currently have. That fact is undeniable, evidenced by the number of people the system has failed.

But rather than confront that failure, some are instead pretending that the wave of anger sweeping the nation is the performative part of some ‘cultural Marxist feminist plot’, and not just women who are sick and tired of being violently assaulted and abused by men. Others are making more reasoned arguments for the status quo. Arthur Moses SC told Four Corners: “If you determined who was to be the subject of an inquiry based on who they are and based on what the alleged crime is, that is not how we operate within this country and I think it takes us down a very worrying road as to what may happen in the future.”

I don’t doubt people defending the criminal justice system are people of good intent. I don’t doubt that they love and honour the women in their lives, and I believe that they want the best for them. I believe that they believe passionately that their way is the best way, and that the best way to get justice for women – for anyone – is to have faith in the principles that underpin our criminal justice system. I also think they’re wrong, and I think the evidence that they’re wrong is utterly overwhelming.

Equally, I understand the point Moses SC is trying to make, although I think the metaphor is unfortunate. I think the ‘worrying road’ he describes is far less worrying than the road countless women walk down every night. And some of them never reach their destination. Women like Theresa Binge. And Jill Meagher. And Euridice Dixon. And Aya Maasarwe. And Anita Cobby. And Janine Balding. And the list goes on and on and on.

Regardless, I think Arthur Moses SC, and others who defend a system that is so clearly not working, should be worried. The claim advanced by some that we can’t have an inquiry into allegations levelled against the Attorney General because it would be ‘unprecedented’ is wrong. It wasn’t unprecedented when Christian Porter ordered an investigation into Dyson Heydon, but even if it were, we’re living in unprecedented times.

We need an independent inquiry into allegations Porter raped a 16-year-old girl, not because we’re second guessing our justice system, but because our justice system isn’t working, and broken or otherwise it clearly can’t be headed by a man facing allegations he raped a child. That inquiry, ironically, might now come through the defamation action Christian Porter has launched against the ABC.

But more than that, we need an independent inquiry into the entire justice system, and why it continues to fail more than half the population. As Hannah Gadsby herself might say, this problem is bigger than Christian Porter’s reputation. And if you think about that – if you flip things around the way our justice system has for hundreds of years and stop to think about how the ‘biggest law of them all’ (our constitution) works – there’s one other final, deep irony.

“Donald Trump, Pablo Picasso, Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Woody Allen, Roman Polanski. These men are not exceptions, they are the rule. And they’re not individuals, they are our stories. And the moral of our story is, ‘We don’t give a shit. We don’t give a fuck about women or children. We only care about a man’s reputation.’ What about his humanity? These men control our stories, and yet they have a diminishing connection to their own humanity. And we don’t seem to mind so long as they get to hold onto their precious reputation. Fuck reputation. Hindsight is a gift. Stop wasting my time.”

– Hannah Gadsby, Nanette

Another perspective

Like 1988, the year of Australia’s bi-centenary, 1770 was also an auspicious year, depending on your perspective, and not just because Captain Cook ‘discovered’ Australia. On February 16, three weeks after Cook set foot on Cadigal land, a man named William Blackstone was finally, after numerous failed attempts, appointed as a Justice to the Court of Kings Bench. That same year, Blackstone’s ‘magnum opus’ – Commentaries on the Laws of England – was reprinted for the first time.

The four-volume Commentaries, as it’s more commonly known, was considered the seminal text on British law at the time, and it would go on to be reprinted countless times in numerous countries for the next 100 years. To this day, Blackstone’s work is still studied in law schools throughout the western world. He’s most famous for an idea known as Blackstone’s ratio: “… all presumptive evidence of felony should be admitted cautiously, for the law holds that it is better that 10 guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.”

It’s one of the most famous legal concepts ever created, and it’s also a saying frequently butchered, particularly by conservative politicians. Here’s former Attorney General Phillip Ruddock doing just that while introducing an anti-terrorism bill to parliament: “Our common-law system is predicated… [on]the sorts of propositions that we all understand: that it is better that 10 guilty men go free than one innocent person be convicted.”

Ruddock obviously meant ‘persons’, not men. Probably. Either way, Blackstone’s ratio is one of the foundational principles on which our criminal justice system is based. Our legal system, however, is much bigger than just the part that deals with crime. Australian law already understands that sometimes individuals are going to suffer in the pursuit of a greater good. That’s actually one of the foundational principles of constitutional law, the ‘biggest law of them all’, according to Darryl Kerrigan from The Castle.

The principle of ‘common good’ is where the term ‘Commonwealth’ comes from, and it’s the reason why governments have the power to compulsorily acquire your home if it’s standing in the way of a new hospital (or airport extension, in Darryl’s case). You lose your house, but 50,000 people gain better health care.

To put it another way, just as 10 guilty ‘men’ must go free so that one innocent man doesn’t go to jail, why isn’t it also the case that some innocent men may have to suffer the loss of their reputation so that many other persons finally have a chance at justice? And by many other persons, I’m referring to women… just over half the Australian population. The fact is, innocent men going to jail for rape and murder – or simply losing their reputation – is the absolute exception to the rule. Men not going to jail having committed rape is the rule.

Of course, under Australian law, if you lose your house you must be compensated for that loss on ‘just terms’. And if there’s one thing we know about the Australian political system, it’s that Christian Porter will be compensated by his mates in power, regardless of whether or not he’s innocent of the allegations levelled by Kate.

We know that because the political party to which he’s a member elected Tony Abbott their leader, despite a history of deep misogyny. We know that because the same party didn’t bat an eyelid when it emerged that Nationals MP George Christensen spent more time in the Philippines, some of it in ‘adult bars’, than he did in parliament. We know that because Scott Morrison believes that a woman who has campaigned for the freedom of Julian Assange – a man jailed and tortured for almost a decade for publishing government secrets about slaughter and war – can be easily dismissed as a sexualised joke. And we know that because Andrew Laming gets to keep his job until the next election, despite clear evidence he hounded and harassed multiple women over years, and upskirted another.

What compensation, you might ask, was ever considered for someone like Kate? Or my friend, who stared down her attacker in court, to no avail? Actually, I can answer that: my friend was reimbursed $1,293.65 for witnesses expenses for taking several days off work, and travelling interstate twice. She also got a dozen free sessions with a counsellor.

If Andrew Laming ever sees the inside of a court, it will be as an alleged sex offender, not a witness. And, until Scott Morrison finds the courage to call an election, Laming will continue to collect his annual parliamentary salary of $211,250, plus $32,000 in ‘electorate allowances’, a government chauffeured car and a private car (or $19,500 in additional allowances), accommodation and airfares when he travels (including an additional allowance of up to $457 per day), free home and phone and internet, plus 15.4 percent superannuation, which is almost double what the government says everyone else should get.

And speaking of numbers, as the name infers, that’s all Blackstone’s ratio really is. Numbers. The question is, what should those numbers really be today, when we talk about the sexual assault of our women?

You might be comfortable with the statement ‘Ten guilty persons must go free so that one innocent doesn’t suffer’. But are you as comfortable with the statement, ‘150 rapists should go free so that one innocent doesn’t suffer?’ Because that’s what our system tolerates today.

And when does the principle of ‘common good’ kick in? Why doesn’t the principle underpinning the ‘biggest law of them all’ trump the principle that has seen countless rapists walk free? Because you can be certain that if Scott Morrison decides he wants an airport extension and your house happens to be in the way, the common good will kick in tomorrow. So why doesn’t it kick in when 201,000 women are sexually assaulted in a 12-month period, and less than 1 per cent of the men who assaulted them are sent to jail?

In Australia today, Blackstone’s ratio might better be expressed like this: ‘It is better that 201,000 women suffer every year so that one man doesn’t lose his reputation.’

If Porter is actually innocent, then perhaps he can find some comfort in knowing that, as a man who has devoted his life to justice, and once served as the highest law officer in the land, his suffering has served a common good? It’s a lot to ask of anyone, although it’s only half of what we ask of so many women every day. Because the fact is, Porter will never see the inside of a courtroom on this issue. His suffering might help him better understand how it feels to be brutalised by the system, but he still won’t know what it feels like to be raped, and then blamed for it.

Kate, of course, will never get to take comfort in any of it. And unlike Porter, she’s not around to contemplate whether or not her suffering was worth where we’ve landed today. Kate felt that she had no voice in life, and it’s a cruel irony that she has one now in death, even though she’s not here to speak for herself. But there are millions of ‘Kates’ out there, and so the best I can do is give the last word to women who were raped, but who survived. Women whose perspectives on a justice system that failed them are invaluable if we’re to fix it and make it finally work for the ‘persons’ it claims to serve.

First, comedian Hannah Gadsby, whose wisdom and generosity of spirit helped guide this essay, but more importantly helped kickstart the process of better understanding another perspective.

“Laughter is not our medicine. Stories hold our cure. Laughter is just the honey that sweetens the bitter medicine. I don’t want to unite you with laughter or anger. I just needed my story heard, my story felt and understood by individuals with minds of their own. Because, like it or not, your story is my story. And my story is your story.”

And finally, to my beautiful friend, who put her faith in a justice system that not only failed her, but added something so much more than insult to the injury.

“Our legal system reflects how we really feel about women. A woman’s life is not as important as a man’s reputation. That must change.”

* DECLARATION TO READERS: Michael Bradley (from Marque Lawyers), who was assisting Kate before her death, has provided pro-bono legal services for New Matilda since 2015. Nina Funnell is part of New Matilda’s investigative reporting team.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.