DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

There’s always room for individual action aimed at solving big problems. But if the COVID-19 crisis has taught us anything, it’s that a collective response is the best way forward to tackle a global issue that confronts us all. Dr Rebecca Colvin weighs in.

I study social responses to climate change. Or to abstract it a little: social responses to a mostly invisible, deeply political and divisive, collective action problem with inequitable social impacts and the potential for clever policy to genuinely fix the problem and improve our world…. So, perhaps there are some parallels to our COVID-19 dilemma that are worth exploring.

Climate change questions our modern lives. We feel its accusing glare when we turn on the lights, when our hot shower runs longer than it should, when we use the car instead of the bike to buy our groceries, and in rapid-fire succession with every item we pick off the shelf at the store.

Some of us spend more in efforts to pay a price that captures a truer cost of consumer items, in the hope that by internalising otherwise unaccounted costs we can hold up our chin and meet the glare’s gaze.

Some of us spend less; we avoid plastic, we don’t buy palm oil, we buy less beef. We go without and trust that the glare can’t find us if we don’t provoke it.

Sometimes these changes see us cross paths with others who do the same. We find our people. Other times these changes demonstrate to folks how they too can change their lives, and they join us (such is the power of social norms). Individual choices bond us with others who do the same, as we share a common struggle against climate change. We see our morality in each other, and know that we are Good People doing the Good Things against the Bad Thing.

But, these same actions can divide us from those who can’t do them alongside us. We swap our petrol car for electric, we change to ethical superannuation, we eat low-emissions food, and then our presence adds to the weight of the accusing glare directed at those who have not done the same.

Our changed behaviours become markers of belonging to the Good People, a group that often requires as a condition of membership expenditure of financial resources and time, two things unavailable to many people.

If it’s too hard or impossible to join what you do you? Accept your inferred moral inferiority, or rail against those who make you feel the glare?

Such is the trap of prioritising individual responsibility in responding to climate change. It paints our lives with guilt, it guides us to surveil and scrutinise, and directs us to see enemies in the people in our neighbourhood, at the supermarket, within our families.

Individual behaviour change is also unlikely, in terms of emissions reduction potential, to solve the problem of climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s 2018 Special Report on 1.5 degrees of warming told us that we need to pursue transformational changes to society to address climate change.

This necessarily extends beyond individual, consumer-style behaviour changes, and redirects our attention to those levers that very few individuals can pull on their own: the origin of electrons in the electricity system; the availability of infrastructure to support active travel; revenue recycling from the profits generated by natural resource exploitation; building and planning standards and enforcement; regeneration of vast tracts of degraded land; packaging and recycling standards; increasing the amount of time available to working people so as to enable exploration of and experimentation with genuinely sustainable ways of living.

But, an individualised approach fits with our individualised modern lives, shaped as they are by our individualistic culture. Australia’s top TV shows are Married at First Sight, My Kitchen Rules, and The Block. If we can accept these programs as an indicator of our culture, what do we learn? That we care about questions like how attractive is your mate? And how impressive is your food? And how beautiful is your home? Questions resolved by competition and status; of an individual’s meritocratic superiority and their triumph over others. It is no wonder that living within this individualised cultural paradigm so many of us feel the glare of climate change following our every move.

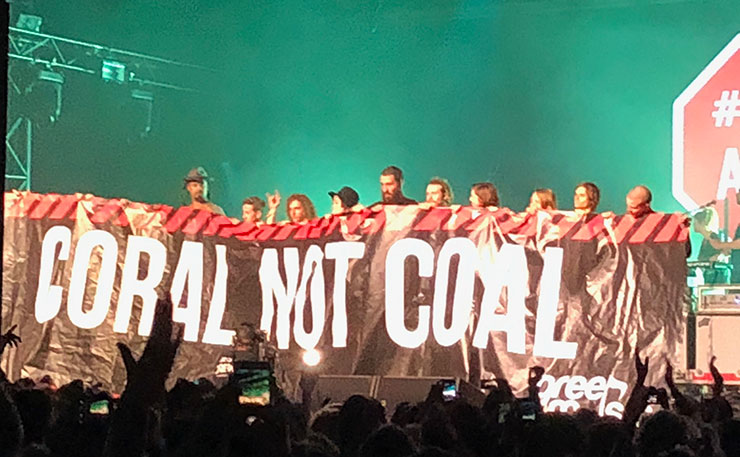

An alternative way to view how we can respond to climate change is to think not about our individual responsibility but our collective power. Our collective power to demand accountability and meaningful action from governments and corporates. Our collective power to direct the accusing glare of climate change toward those who can make a difference, but choose to not. But how do we foster a sense first of collectivism, and then with this wield our collective power?

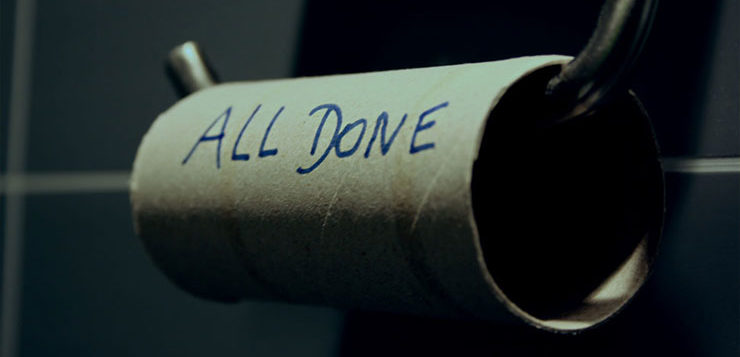

In a roundabout way this brings me back to COVID-19. We’ll all remember the virus, the suffering and deaths, the lockdown and isolation, the economic and social disruption. But we’ll also remember toilet paper: the curious and perhaps confounding consumer rush on one of the most mundane and unglamorous household items.

Videos of physical violence spurred by dwindling toilet paper supples in Australian supermarkets were viewed around the world. Toilet paper panic-buying dominated conversations, and fuelled sneering on social media and discussion by the commentariat. Government leaders implored the public to stop and supermarkets implemented limits on purchases.

Many despaired at what was taken as a mass display of puzzling selfishness: individuals acting to secure their own excessive supply causing shortages that deprived others of basic access to an item important for hygiene and dignity. Psychologists helped us to understand such behaviour, noting that this type of response is expected in times of stress, fear, and uncertainty. Despite this, it remains easy to think the people who panic-bought are unlikely to make a constructive contribution to addressing the collective action challenge that is climate change. To think that they’re not of the Good People.

But there may be a deeper story here, one that matters for unpacking how we have responded to COVID-19 and each other, and understanding how to address climate change. Rather than decrying the failure of individual responsibility of those who contributed to emptying the shelves of toilet paper, we can consider instead what the toilet paper panic-buying of 2020 tells us may be percolating beneath the surface.

To me, the empty supermarket shelves tell us that in a time of crisis we feel alone and afraid. We feel that we have to fend for ourselves, that we have to fight our neighbours, and that certain doom awaits us if we don’t act individually and selfishly to secure ourselves and our families.

In one of the world’s wealthiest countries, we feel like we are teetering on the edge of a cliff, and that if we don’t act for ourselves and against others we’ll plummet into the chasm. The great toilet paper panic-buying of 2020 tells us that too many people feel their needs are not satisfied by the individualised social and economic systems we have created.

And here I return to climate change. If I was to characterise my understanding of the world in a single word, pre-2020, I would say ‘ambivalence’. But 2020 in all its upheaval has provided some certainty: that we need to stand together and find new ways to build connections across differences that have divided us. That we need to ensure the accusing glare reaches those with power who use it not to make positive change but instead to deny, delay, misinform, or seed disunity to the benefit of few but detriment of many. That the glare shouldn’t be monitoring individuals, but instead be interrogating individualism.

For those of us working in climate policy research and practice, we need to consider how well-intended actions might ultimately work against establishing the necessary social pre-conditions for real solutions. Do our approaches to climate policy advocacy push us together or apart? Do they steer us toward or away from individualism?

To me, this is the critical question made clearer than ever before by COVID-19 and its toilet paper panic-buying. If the answer is ‘toward’, then I think we need to ask whether the gains we seek to achieve are worth further entrenching individualism. If the answer is ‘away’, then we should forge ahead urgently.

COVID-19 has shown us that if social needs are not met, our ability to respond effectively to crisis is nobbled. If we want a lesson from COVID-19 to inform how we approach climate change, I think this is it.

Real solutions to climate change will likely remain out of reach if we focus solely on individual responsibility. But it’s not just a problem for climate change; COVID-19 shows us that our social needs, well beyond the context of climate change, demand that we challenge individualism.

Living as atomised individuals in a culture imprinted by competition and status neither helps us address climate change, nor feel secure in the face of a crisis like COVID-19. Maybe a common cure to our crises starts with looking beyond securing immediate-term wins and rethinking how we relate to each other.

BE PART OF THE SOLUTION: WE NEED YOUR HELP TO KEEP NEW MATILDA ALIVE. Click here to chip in through Paypal, or you can click here to access our GoFundMe campaign.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.