DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Things didn’t really go to plan for the Liberals in the final week of campaigning. Or maybe they did. Ben Eltham weighs in.

The final week of the campaign has proved puzzling, if not dizzying.

The policy discussion, such as it has been, turned to housing, with the Coalition’s hastily conceived first-home owners’ guarantee announced to a half empty Melbourne Convention Centre on the final Sunday.

On first glance, it looked like it might be a vote winner – directly addressing the huge demographic of middle-class families increasingly locked out of owning a home. But after some scrutiny from economists and policy wonks, it soon became clear that the policy would be only marginally significant. It wasn’t a true first-home owners grant, but rather a government guarantee to help home buyers with less than the required 20 per cent deposit. And it would be limited to 10,000 people a year.

Labor matched the policy almost immediately, a mark of the party’s ruthlessness, but also of the limited economic impact of the Coalition’s policy. This also served to highlight the inherent failures of the Coalition on housing, which has done little to increase housing supply.

Property prices are falling. This hurts home owners. But even with big falls in Sydney and Melbourne, housing is still not affordable for first home buyers. Working families struggling to save enough for a deposit might be lured by the Coalition’s promise. Or they might be disgusted by the government’s single-minded commitment to tax concessions for wealthy retirees. It’s hard to tell.

Other spectres loomed. A proper viral scare campaign is underfoot online, supposedly claiming that Labor will introduce a death tax. In the pathless wilds of social media, it’s impossible to track the spread of such a rumour, but it is surely causing the ALP damage. Certainly, the anti-Labor message on taxes is cutting through.

The Coalition’s final week has hardly been blemish free. A fresh outbreak of infighting broke out with squabbles between Barnaby Joyce and Jim Molan. Some costings were released, but few paid any attention to them (for the record, the Coalition will save $1.5 billion by outsourcing public service roles to the private sector).

By Tuesday the Coalition’s campaign had largely wound up, as ministers and backbenchers returned to their seats for the final days of the campaign. The Coalition’s grand strategy has been a scare campaign across 151 by-elections. Depending on Saturday’s result, this will either be hailed as a stroke of genius, or panned as a flawed strategy doomed to defeat.

Can the Coalition win? Of course it can. It is entirely possible to win a federal election with 49 per cent of the two-party preferred vote, as John Howard proved in 1998. If Labor’s swing is mild, and if the swing is concentrated in its own safe seats, and if the government can hold its own seats, and win a couple here and there, Scott Morrison can absolutely hang on.

But even to enumerate it thus shows the narrow path to victory the Coalition must tread. It needs to stem its losses, maximise its gains, and a smiling fortune of luck. Morrison needs above all a decisive advantage amongst undecided voters, the people who have remained disengaged until now. As Malcolm Farnsworth pointed out yesterday in Meanjin, “the Coalition has not won a single opinion poll since the last election. “That probably tells us something.”

Labor’s task is simpler. It needs to turn its nationwide polling advantage into seat-by-seat victories. There are Coalition seats vulnerable across the nation; just a handful are required to secure government. The smallest margins are in Brisbane and Sydney, but Labor’s best prospects are in Victoria, Australia’s most left-leaning state. A small swing in south-east Queensland will quickly deliver Labor victory. While the swings required in Melbourne are larger, the Coalition vote there also seems softer.

The anxiety of senior Liberals in what should be safe seats is palpable. Driving through affluent suburbs of Kooyong and Camberwell this week, all one could see were Josh Frydenberg posters. His stubbly face grins down from nearly early every billboard. The Liberal Party has never needed to sandbag Kooyong like this before.

Even so, by mid-week there was just the faintest hint of a tightening in the polls. How real it was, nobody could tell. The whispers from party insiders spoke of New South Wales passing firmly into the Coalition’s column; seats like Lindsay looked achievable for the Liberals, while Dave Sharma was said to be looking good in Wentworth. In Queensland, Labor’s momentum seemed to have stalled. The Coalition spoke confidently of holding its marginals in greater Brisbane, and picking up a couple in the north. In Victoria, though, Labor remained confident.

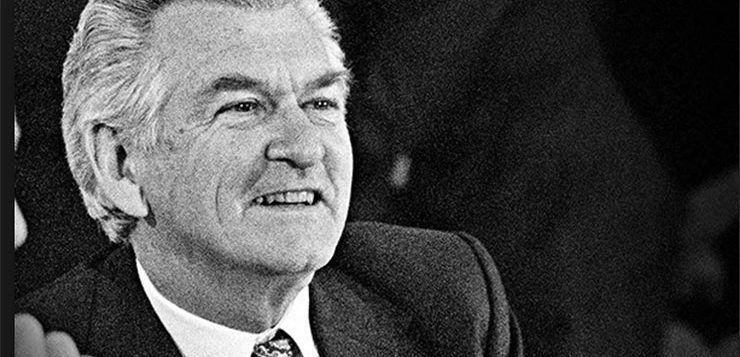

And then, on Thursday night, Bob Hawke died. The passing of the Labor legend flooded the media with gauzy memorials, most of them recalling Hawke’s legacy as the “father of Medicare” and his celebrated charisma with the common man. Whatever momentum the Coalition might at last have generated was immediately buried in avalanche of remembrance for the passing giant.

A pre-election column in New Matilda is not the place to assess Hawke’s capacious political and symbolic legacy. A few short remarks will have to suffice.

Firstly, Bob Hawke was a great trade unionist. His career at the ACTU was already legendary before he entered parliamentary politics; in a time of endemic industrial unrest, he was seen as a negotiator and a conciliator. Hawke was the last true hero of the union movement to ascend to the prime ministership. Not a working class lad, he was in fact a middle class boy brought up with a keen sense of his destiny. But he was subtle in the art of consensus, and unusually skilled at working with talented colleagues.

This skill would serve the nation well when Hawke led Labor to victory in 1983. He inherited the most talented cabinet in post-war Australia. In addition to Paul Keating, the early Hawke government boasted intellects of the calibre of Gareth Evans, Brian Howe, Barry Jones, Susan Ryan, John Button and Neal Blewett.

Hawke led the Labor governments that deregulated and neoliberalised Australia’s economy. Many on the left in Australia fought these reforms at the time, and many still oppose them now. It is a conflicted legacy: Australia walked away from many of the proudest post-war achievements of Labor governments, including full employment and a welfare state that protected the poorest and most indigent.

Hawke also embraced reforms that would eventually be seen as fundamentally regressive, such as a user-pays higher education system, a fundamentally deregulated Australian banking system, and an industrial relations system based on workplace flexibility and wage restraint.

At the time, of course, these reforms were seen as good ideas. Labor under Hawke thought that they would make the Australian economy more open and more competitive in world markets. Some reform was obviously necessary: Australia’s economy in 1983 was protected, closed and sclerotic, with a de-industrialising rust belt in Melbourne and Adelaide, and a services sector only just beginning to grow into the employment juggernaut it is today. There is no doubt that Australia prospered in the years after Hawke left the prime ministership. Whether this was in spite or because of the neoliberal reforms of the 1980s is still a question debated by economists and historians today.

It is Hawke’s social policy achievements that stand the test of time. His commitment to women’s issues revived the pioneering progress made by Whitlam. It was under Hawke that Australia adopted a world-leading approach to combating the spread of HIV. After the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, Hawke impulsively committed to giving all Chinese students then in Australia asylum. No prime minister since has showed such generosity of spirit to migrants. Hawke fought racism and apartheid with a hard head and warm heart. He played a key role in ensuring that Australia made the transition to an open, flexible economy with key aspects of the welfare state intact. It is hard to imagine Bob Hawke reducing the benefits of 80,000 single mothers, as Julia Gillard did.

The impact of Hawke’s death, just two days before federal polls open, is difficult to appraise. Clearly, Labor will be buoyed by a wave of nostalgia for Australia’s best remembered prime minister of modern times. Rudd was more popular, at least briefly; Howard won more elections.

But no prime minister in modern times captured the public imagination like Hawke. In part, this is the action of the passing of time. When we think about the 1980s in Australia, we generally think of Hawke. The clips of the America’s Cup victory, of the 1983 Accord summit, or of Hawke campaigning amongst adoring crowds have passed into the Australian symbolic imagination. Younger voters may not remember him at all; for Gen X he is the technicolour of childhood; for younger boomers, part of the fabric of their adult lives. Even before he died, Hawke was the subject of a hagiographic television biopic, with the silver bodgie played by Richard Roxburgh.

Hawke’s death can only help Bill Shorten. The Labor faithful will take some of that aura of charismatic reform to the polling places, campaigning for one more chance at a light on the hill. The impact will probably be relatively minor in the scheme of things, but Labor will be grateful for every extra vote.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.