DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

This is an edited extract from Rise of the Right by Greg Barns, published by Hardie Grant Books.

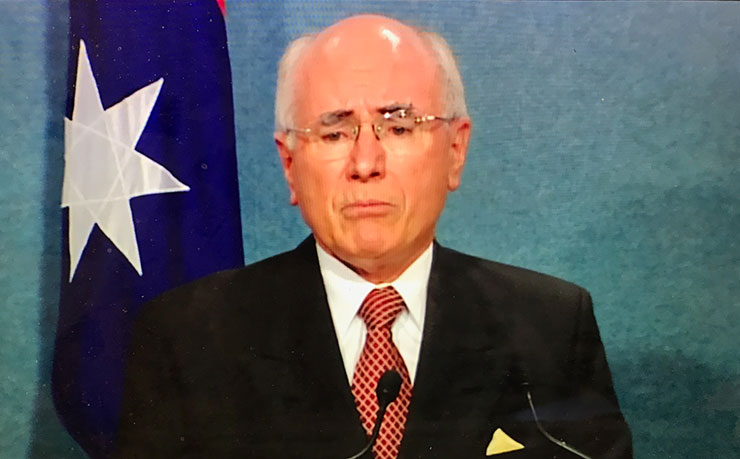

As One Nation and Pauline Hanson make the front pages yet again, this time over the quest for funding from the NRA in the US, it is worth pausing and reflecting on the pivotal role played by former Prime Minister John Howard in giving Ms Hanson traction and longevity on the Australian political scene.

Many have forgotten the kid glove treatment Mr Howard gave Ms Hanson when she first created headlines in 1996. Howard’s response to Hanson’s first speech to parliament that year remains an early pivotal moment in the rise of populist right politics in this Nation.

Hanson’s speech, delivered on 10 September 1996, not only caused outrage and uproar but also unleashed and gave voice to what might be termed white resentment politics. It seems forgotten today, because the cultural phenomenon of Pauline Hanson is now so embedded in the Australian political and public psyche.

Hanson’s theme in that speech was one of dispossession: the Anglo-European way of life is under threat; working-class whites are being discriminated against by government. Held up as scapegoats were iconic examples of liberal values – such as multiculturalism, redressing the historic and current injustices to Indigenous Australians through land rights reform, the Family Law Act, immigration, foreign aid, and open markets. Hanson even quoted approvingly the racist cant of the former Labor leader Arthur Calwell, who once said,

“Japan, India, Burma, Ceylon and every new African nation are fiercely anti-white and anti one another. Do we want or need any of these people here? I am one red- blooded Australian who says no and who speaks for 90% of Australians.”

Hanson’s speech was a typical nativist speech: simplistic, bereft of analysis and empirical data – and angry. What was more significant, though, was the fact that Howard as prime minister bothered to reply to a neophyte backbencher who had been dumped as a candidate by his own party. Instead of a no ifs or buts–type response to Hanson’s diatribe and trashing of the liberal agenda, Howard sought to court her voters and at the same time ignore Hanson.

On 28 October 1996 Hanson asked Howard whether he would cut Australia’s foreign aid budget so the money could be used for civil construction and national service. Howard answered unequivocally in one sense. He upheld the idea of foreign aid and the level of it at the time. But equally he was at pains to point out, in what was a relatively short answer, that he could ‘understand the feelings of Australians who think that their taxes are wasted in relation to aid to those countries’ and that he could ‘understand why, in times of difficulty – in particular, in areas of economic and social difficulty in Australia – some Australians would look suspiciously upon the provision of foreign aid’. He thought Hanson had raised ‘an important question’, and that she of course was ‘entitled, like any other honourable member, to ask questions in this parliament, and [he would]endeavour to answer it as comprehensively as [he could]’.

This was a clever response by Howard because, while it defended the government’s position, it sent a clear message to Hanson and Howard supporters that this prime minister was somewhat sympathetic with their position, and that he would not ignore them or even seek to set them right about their views.

Hanson of course fitted within the broader project of Howard’s promise that he believed a pall of ‘political correctness’ had been cast over public discourse in Australia before he assumed office in 1996, but that he wanted a ‘relaxed and comfortable’ nation where people like Hanson and those who supported her illiberal and nativist sentiments could feel free to speak without fear of reprisal.

The fact that Hanson’s every utterance, including her first speech, was being writ large in broadcasts and newspapers across the nation was damaging to cohesion in Australian society, and its reputation internationally seemed less important to Howard than his cynical strategy of using Hanson’s extremism for support in political terms. It suited his failure to uphold social, as opposed to economic, liberal values.

Ten years on, Howard was still defending his failure to confront Hanson. And then she rose again and found herself elected as a Queensland senator in 2016. Hanson produced another stock-in-trade nativist first speech. This time Asians had been replaced by Muslims as the existential threat to Anglo-European Australia.

At a media conference in July that year Howard defended his decades-old approach to her: “I didn’t agree with her when she said we were being flooded by Asians because we weren’t, and I didn’t agree with her when she said that Aboriginal people weren’t amongst the most disadvantaged in our community because those things were manifestly wrong.”

But it needed to be remembered, he said, that Hanson was “articulating the concerns of people who felt left out”. And to attack Hanson was then, and it is now, a mistake, according to Howard, because the more she was attacked, “the more popular she became because those attacks enhanced her Australian battler image and she plays off that”.

Howard’s failure was, and remains to this day, that he did not make a full rebuttal of Hanson’s dangerous, divisive rhetoric. To say people vote for her and support her views is to say that he, as a leader, had no business in seeking to stand unambiguously for liberal values, particularly social liberalism.

Instead he would, and did, pander to the nativist and reactionary toxicity that Hanson and her supporters represented and still represent today.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.