Relations between Pakistan and India over the disputed region of Kashmir are at a low point, but there are ways to broker peace, writes Lee Rhiannon*.

Collateral damage comes in many forms when hostilities break out. For Kashmir-Jammu it is not only deaths and injuries caused by the suicide bomber who in mid-February killed about 40 Indian paramilitary forces. Finding a pathway to peace and justice for the people of this region could also be on the rocks.

Initially there was hope that with worldwide media attention on the military escalation over the disputed status of Kashmir, support would build towards a resolution of this 70-year-old conflict. But at the same time the 24/7 Indian media networks have had unrelenting coverage, with many advocating revenge for the killing of the Indian security personnel.

Social media users in India have amplified the vitriol towards Pakistan and anyone deemed to be unsupportive of the Indian government. The wife of one of the security personnel killed in the February bombing, Mita Santra, was even targeted with online abuse because she called for peaceful dialogue with Pakistan and said war should not be an option.

A number of academics at Indian universities are suffering shocking consequences for questioning how the Modi government is handling the conflict. When Madhumita Ray, a professor in the state of Odisha, advocated in a television debate that India should not go to war against Pakistan she lost her job. Other leading academics have been humiliated for similar comments.

An emotional response from India is understandable. The killing of 40 of its citizens in one attack is shocking. However, for local Kashmiris there is the context of decades of violence that can be traced back to how Britain in 1947 divided up the sub-continent between India and Pakistan.

While India has blamed Pakistan for the attack, Imran Khan’s government has denied any connection with the suicide bombing, which it has condemned.

The suicide bomber, Adil Ahmad Dar, lived in Indian-controlled Kashmir and was a member of the local militant group, Jaish-e-Mohammed. Dar’s parents said their son became radicalised after being beaten by Indian police when he was returning home from school. His recruitment reflects the deep-rooted resentment among young Kashmiris towards Indian forces.

Human rights groups that monitor the violence in India-controlled Kashmir report that 528 people died in 2018, including 145 civilians. This is the deadliest year since 2009.

The level of death and suffering is even higher than these figures suggest. Indian author and political activist, Arundhati Roy, writing earlier this month stated: “Since 1990, more than seventy thousand people have been killed in the conflict, thousands have ‘disappeared’, tens of thousands have been tortured and hundreds of young people maimed and blinded by pellet guns.”

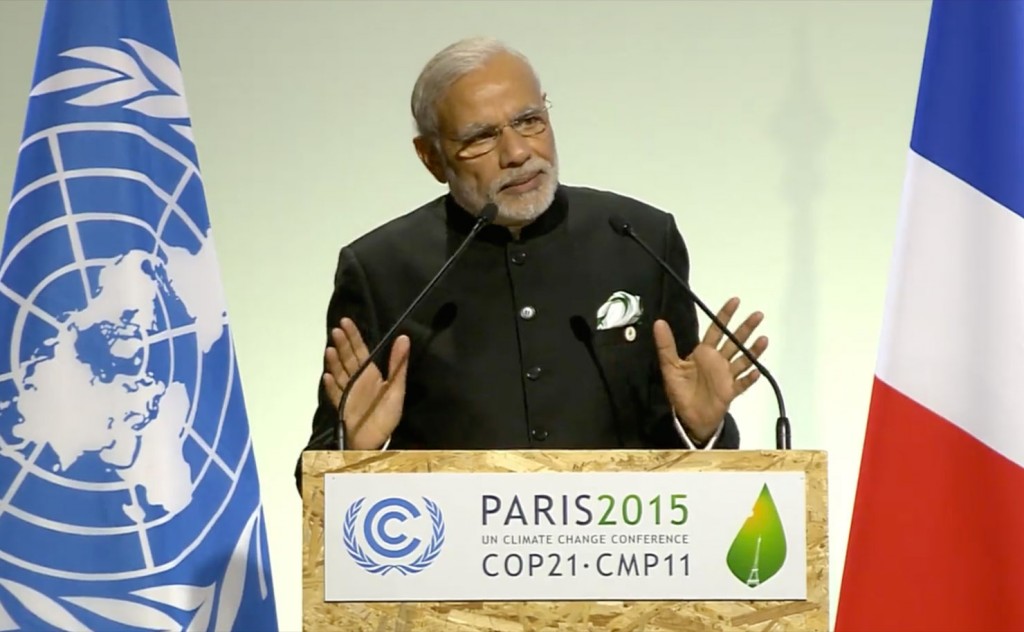

The differences between Pakistan and India are stark. While Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan called for a diplomatic solution to the current crisis and said his government’s response to India’s air strike was to ensure there was “no collateral damage, no casualties”, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi followed a belligerent path promoting Hindu nationalism. In the immediate aftermath of the suicide bombing Modi committed to “a crushing defeat” of Pakistan and promised a “jaw-breaking response” involving retaliatory “surgical strikes”.

The Australian Strategic Policy Institute identified that this was “the first time that Indian forces have released munitions into Pakistan’s undisputed territory since the 1971 India-Pakistan War”. ASPI was established in 2001 by former Prime Minister John Howard and is part-funded by the Department of Defence.

The same ASPI report stated that these strikes “were designed primarily to placate a domestic (Indian) audience while simultaneously limiting escalation by not targeting built-up areas and causing substantial casualties”. While some comfort can be taken from this analysis, as it suggests that Modi wanted to avoid an ongoing war, his approach does not develop a pathway to peace and justice for Kashmir. What’s more his bellicose statements targeted to a domestic market are inciting deep divisions among Indians towards Kashmiris studying and working in India.

There have been numerous reports of Kashmiri students and business people being harassed and in some cases Indian students have demanded the expulsion of Kashmiri students from their university. A sign of the seriousness of the attacks is that the Indian Supreme Court has ordered the government to protect Kashmiris living in India. Many of the more than 11,000 Kashmiris studying at Indian universities now want to return to their homes in Indian-controlled Kashmir where reports of their treatment are sure to reinforce the growing anger Kashmiris feel towards India.

This controversy is happening in the hot house of India’s general election campaign. From the moment the suicide bomber set off this latest wave of death and destruction a number of commentators speculated that the killings could help the Modi government win the election scheduled for April and May this year.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Both Forbes and the Economic Times have explored the boost they expect Modi to gain from the bombing and cross border air strikes. Prior to the suicide attack Modi’s chances of retaining power was put at 50:50 after his Bharatiya Janata Party was defeated in five state elections in 2018, including in the key Hindu states of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh.

Post the February attacks Modi’s chances of re-election have been pushed to 70 per cent. The Times of India speculates that “a strong leader who acts tough” could swing the required “20 seats” to win.

With Modi’s re-election platform dominated by nationalist zeal, as he has been unable to deliver on his economic and development promises, there could be a repeat of the 2014 general election when Modi won power largely due to his “strong leader” image.

There is a risk that this could plunge not just Indian-controlled Kashmir but the whole sub-continent into more chaos. A re-elected and re-invigorated Modi government could move to declare India a “Hindu rashtra” (Hindu nation) by amending the nation’s constitution. Arundhati Roy has predicted this would be an upper caste nation where “minorities and all those who do not agree with the majoritarian point – can be criminalised”.

The policy of Modi’s BJP sees India as a Hindu country. Implicit in this view is that all Indian Muslims should have moved to Pakistan in 1947. Those that remain in India are viewed as traitors to India. This is the frame for Modi’s response to the current crisis. So an attack such as the recent suicide bombing plays into Modi’s anti-Muslim narrative.

Last year India was added to the United Nations list of countries that regularly inflict reprisals or intimidation through killings, torture and arbitrary arrests against people cooperating with the UN on human rights.

For all the complexity of this dispute, the world cannot again turn away from finding a solution. This is not just because two nuclear powers, India and Pakistan, are facing off against each other. Kashmir, on both the Indian side and the Pakistan side, consists of many different regions with varying aspirations for their future. Not all support autonomy.

Surely the starting point to create the conditions to work through these complexities must be the demilitarisation of this region. Achieving that would be a major step to reducing and eventually ending the ongoing human rights abuses that successive generations of Kashmiris have had to endure. All parties need to respect human rights including freedom of speech and movement.

Multilateral bodies along with individual countries have a role to play in working with India and Pakistan to achieve these objectives. Progress is happening. Last year both the Office of the United Nations Human Rights Commissioner (OHCHR) and the British Parliament’s All Party Parliamentary Group on Kashmir produced reports and recommendations that if acted on will take us down the path of achieving peace and justice for Kashmir and for the whole region.

The key recommendation from the United Nation’s OHCHR is for a Commission of Inquiry that could conduct an on the ground independent investigation in Kashmir. The Pakistan government has agreed that a UN team can “visit Azad Kashmir as long as it is able to visit the J&K (Jammu-Kashmir). In that sense, Pakistan’s stance on the question of ‘access’ by the UN is unconditional as long as India offers similar access to the Territory it occupies.”

So here is the roadblock. The Indian government does not agree with setting up a Commission of Inquiry. The Pakistan government does support establishing the CoI but it will only agree to the Inquiry visiting and investigating in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir if India reciprocates for the region it controls.

Leadership is needed. Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan lowered the temperature on the recent conflict by releasing the Indian Airforce pilot after his plane was shot down over Pakistan. Could Pakistan show leadership again by agreeing to the Commission of Inquiry having free movement in the territory it administers irrespective of India’s current position?

This would be a significant step to moving the Kashmir conflict away from death and violence and onto the path to peace and justice.

* Lee Rhiannon is a former Greens NSW Senator and long-time activist on a range of social justice and environment issues. Last year she visited Kashmir and earlier this year she attended a London conference on Kashmir.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.