The Victorian election confirms a major realignment in Australian politics, writes Ben Eltham.

Surveying Victorian politics the morning after the 2018 election, it’s difficult to overstate the significance of this election result. Victoria has confirmed an openly left-leaning and social democratic government. It has repudiated a populist and fear-mongering Liberal opposition.

There were signs from the final week of the campaign that Labor was ahead, and that a swing was on towards the government. But the magnitude of the swing, when it came, surprised everyone – even Labor.

The election was won by the government early in the evening, and as the night wore on and more results rolled in, the gains for Labor kept snowballing. At one stage, it looked as though Labor might even win seats like Hawthorn and Brighton, the bluest of blue-ribbon electorates. On Sunday morning, those seats have inched back into the Coalition’s column. It is some meagre salve for what are otherwise crippling Liberal wounds.

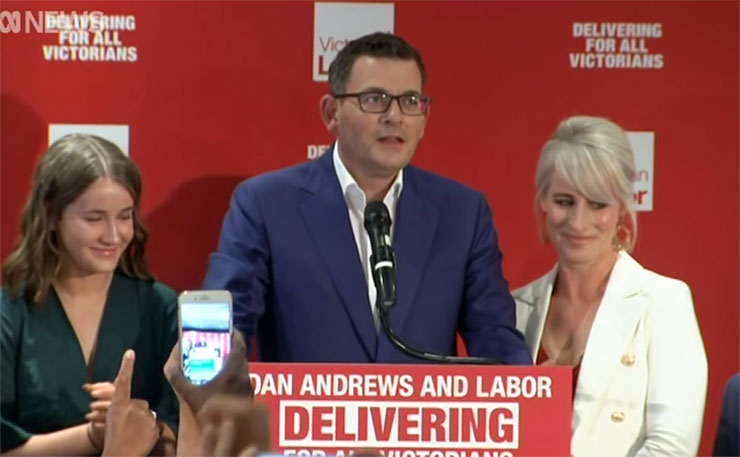

For the victors, the spoils. Labor under Daniel Andrews is triumphant, smashing its way to a landslide victory that recalls Steve Bracks in 2002 or John Cain in 1982. A confident Andrews told local electors in his victory speech that “this is the most progressive government in the country” and revelled in the confirmation that voters had rejected the “low road of fear and division.”

As I wrote in the lead up to the election, Andrews and Labor have run a highly progressive government that has delivered impressive results in infrastructure and core public services. Voters have rewarded that.

Much credit must go to Andrews and his policy team, which have made big decisions on potentially risky issues like elevated rail, assisted dying legislation and family violence, and backed themselves despite plenty of initial criticism. Andrews has also grown in the job, beginning to resemble the confident and open leadership style that so suited his predecessor Steve Bracks.

Most importantly, Labor has got things done. The level crossing removals policy looks like a stroke of genius after this thumping victory. But it wouldn’t have been popular if that infrastructure hadn’t been built – Sydney’s troubled light rail project is a perfect example. Andrews’ determination to push hard on big policies, and to keep pushing hard, has convinced voters that he really does “mean what he says”, as he has often insisted.

Now Labor looks set to hold office in Victoria until 2026. Andrews will seize the opportunity, embarking on transformative infrastructure and social services programs, including plenty of schools, roads and hospitals, more level crossing removals, and a massive orbital rail project for outer Melbourne. It’s a ringing endorsement of a government that has regularly been criticised by many within the party as being too left-wing on social issues, and not responsive enough to the fear campaigns of the right.

For Matthew Guy and the Coalition, defeat is nearly total.

The once-proud Victorian branch of the Liberal Party is a smoking ruins today. Far from challenging for re-election, the Liberals suffered a 6 per cent swing against them. The Coalition has lost more than a dozen seats. It’s a disaster.

The losses have been most devastating in Melbourne’s leafy and affluent eastern suburbs. This is Liberal heartland: seats such as Box Hill, Ringwood and Mount Waverley were safe, conservative-leaning electorates that were not considered in play before polls closed. Losses in Bass and South Barwon on the south coast, and the defeat of National Party whip Peter Crisp in Mildura round out the catastrophe.

The heavy losses can only be read as a stinging repudiation of Guy’s leadership and campaign, which focussed so heavily on crime and law and order, to the detriment of bread and butter issues like health, education and transport.

Law and order dominated the Liberal campaign. Guy’s campaign launch, for instance, featured Liberal members holding up placards that read “jail the gangs”. One particularly draconian policy would have jailed anyone who breached their bail conditions, despite the fact that Victoria’s jail population is already skyrocketing.

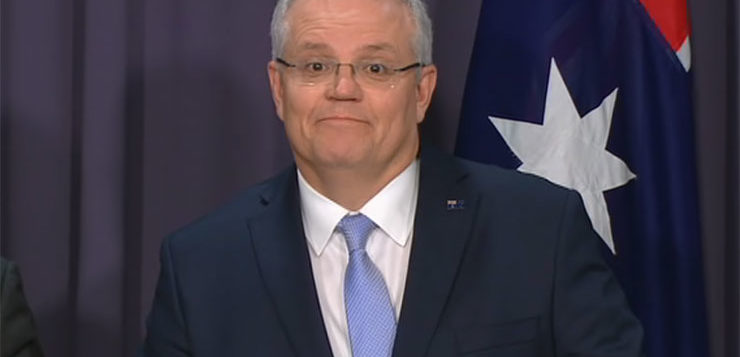

But the fear mongering didn’t work. Perhaps the turning point came on November 13th, when Guy and Prime Minister Scott Morrison staged a high-profile media conference outside Pellegrini’s restaurant in Bourke Street, the scene of the terrorist murder of much-loved café owner Sisto Malaspina.

Like so much of Guy’s campaign rhetoric, it backfired. The media circus, and Guy’s strident anti-immigration rhetoric, left a sour taste in Melburnians’ mouths. Many viewed it as cheapening and politicising what should have been a solemn commemoration.

The outcome was plain to see last night, as Liberal after Liberal member fell in once-safe seats. In particular, the desertion of so many voters in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne looks like an erosion of the core Liberal support base.

This is all the more ironic when you consider so much of the turmoil in the federal Liberal Party has been framed by party insurgents around the idea of satisfying the supposedly conservative Liberal base. That argument has always looked threadbare, as the crushing by-election result in Wentworth demonstrated, and as last night’s result seems to conclusively prove.

As none other than federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg pointed out on ABC radio last night, the Liberal electoral coalition has always been a marriage of conservatives and small-l liberals. This is particularly true in Victoria, the home of Alfred Deakin, Robert Menzies and Henry Bolte, where the Liberal Party has typically been a relatively cautious and centrist force that retained strong elements of social liberalism alongside its pro-business credentials.

In recent years, however, the Victorian branch of the party has shifted markedly to the right. Social and religious conservatives have been active in branch politics and in the party machine, and moderate candidates have been blasted out of preselection by a dominant and motivated hard-right faction. This has also translated into much more conservative policy positions under Matthew Guy. But it looks as though the party has left many of its moderate supporters behind.

Politicians love to say that state elections are fought on state issues, and that there will be no federal implications of last night’s result. Don’t believe them. The terrible result in eastern Melbourne has profound implications for the future of the federal Liberal Party.

If last night’s swing is repeated at a federal election, the government is toast. It could be as many as seven or eight seats in Melbourne’s east and south, including Aston, Deakin, La Trobe, Corangamite, Chisholm and Dunckley. Local factors could compound the problem: in Chisholm, incumbent Julia Banks is stepping down, while in Deakin, Michael Sukkar is a well-known ringleader of the putsch against Malcolm Turnbull.

The federal implications are as much ideological as they are electoral. The rightwards drift of the Liberal Party is a national phenomenon, and the Victorian repudiation of it a possible harbinger of a much bigger bloodbath next year. That will only accentuate the internal divisions roiling the federal party.

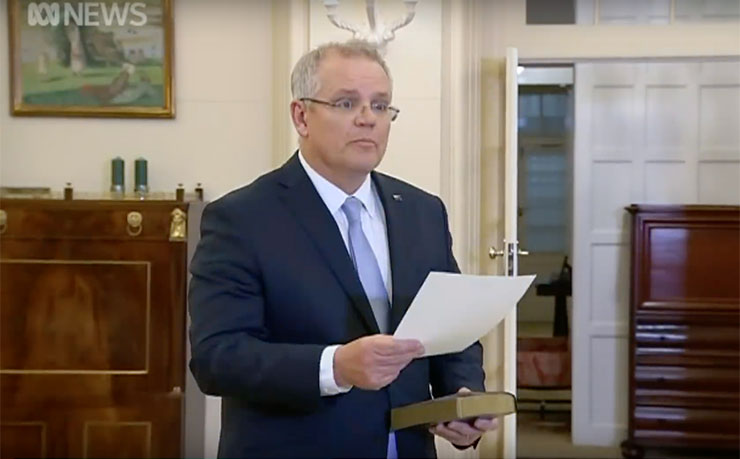

As the situation for Scott Morrison’s government gets ever more desperate, more policy instability and more factional warfare seems certain. That’s great for Labor. But it’s not so great for Australian democracy, as Morrison lurches from gimmick to thought-bubble, in the process doing damage to the nation.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.