Earlier this year, New Matilda sent British journalist Michael Gillard into West Papua, one of the most dangerous regions on earth for reporters. Michael’s goal was to hold to account a well known multinational operating beyond proper scrutiny in one of the world’s poorest regions. This is what he found.

BP is profiting from a giant gas field in West Papua while the indigenous population face ‘slow motion genocide’ under Indonesian military occupation, an undercover investigation by New Matilda can reveal.

The oil giant is collaborating with the army and police who are implicated in the killing and torturing of pro-independence activists as part of an escalating militarisation to secure West Papua’s gas reserves.

Indonesia jails foreign journalists who enter the occupied country without permission. Even the United Nations’ human rights rapporteur has been refused entry.

[the_ad id=”110084″]However, New Matilda snuck into the remote and forbidden land where BP is operating a US$10bn gas field called Tangguh to bring this exclusive report on the human rights quagmire.

Posing as a doctor, the undercover reporter travelled around the highly militarized Bintuni Bay and found evidence that behind a carefully crafted veil of corporate social responsibility, after fifteen years in West Papua, BP is endangering human rights and failing to deliver ‘a material improvement in fundamental living conditions’ of some of the world’s poorest people.

New Matilda can reveal that while still claiming to operate a ‘community-based security approach’:

- BP security guards are spying on the local community and passing intelligence on ‘disruptive individuals’ to the military.

- Well-armed Indonesian security forces are now secretly stationed inside the oil company’s base; And

- Retired senior Indonesian police and military officers are running an ‘elite cadre’ of BP guards armed with stun guns and rubber bullets who are given ‘behaviour profiling’ training in how to spot agitators.

The self-styled ethical oil company is using counter-terrorism to justify these measures. BP is expanding the Tangguh operation at a cost of US$4bn and says it needs to vet thousands of construction workers coming from the Indonesian mainland for possible infiltration by Islamic terrorists.

But even the Indonesian counter-terrorism agency accepts there is no evidence that home grown Islamic militants, some returning from Syria, are operating in West Papua, let alone in the Bintuni Bay area.

Critics fear that the counter-terrorism is a cover for increasing state surveillance on the growing student and social movements seeking political freedoms and ultimately self-determination for West Papua.

The head of the Papuan organisation that provided human rights training to BP security told New Matilda that a network of undercover military intelligence agents is also targeting peaceful social movements in Bintuni Bay, who are being swept up in mass arrests.

The militarisation of BP’s Tangguh operation comes as a recent Amnesty International report on West Papua documented 95 extrajudicial killings by soldiers and police in the last 8 years and thousands of unlawful political arrests.

The scandal of a two-tier health system

West Papua is one of the richest countries in natural resources, with an abundance of gas, gold, copper, fish and timber, yet the ethnic Melanesian population of 3.5m is the poorest in Indonesia and its colonies.

In Bintuni Bay, rural Melanesians, supposedly with tribal rights to the huge offshore gas deposits, continue to live in poverty and are treated as second-class citizens by Indonesian migrants who run the economy and have a significantly higher life expectancy.

Rural Melanesian families are also being devastated by high rates of infant mortality, tuberculosis, malaria and HIV, the latter first introduced by migrant Indonesian prostitutes.

Last week, BP reported bumper profits of US$3.8bn, double those of the previous year. Yet in Bintuni Bay New Matilda found:

- A flagship BP sponsored health clinic serving 3,000 people has been without electricity for six months because the generator was not installed.

- Melanesian villagers are given a cheaper anti-malarial drug while BP employees are treated with a more expensive brand.

- Tuberculosis, a disease linked to poverty and poor housing, is on the rise but since 2002 BP has resettled just a handful of communities and only because it needed their land to build its base.

The communities were rehoused in new model villages but the inequality caused by neglecting the vast majority of remote villages on the north and south shores of Bintuni Bay has caused resentment and division, which Indonesian security forces are exploiting to justify applying counter-insurgency tactics.

Wake up to the slow motion genocide

Senior figures in the clergy and politics have told New Matilda that the international community and United Nations must now face up to its responsibility to confront multinational companies and Jakarta over their conduct in West Papua.

British peer, Lord Harries of Pentregarth, the former bishop of Oxford, said it was “high time the world woke up to the slow motion genocide” taking place and questioned the involvement of one of Britain’s biggest companies.

“BP are siphoning off West Papuan resources to Indonesia blind to the brutal repression going on around them,” he said. “Ever since Indonesia invaded West Papua in 1961 Papuans have been bitterly repressed, with hundreds of thousands being killed. The Indonesian Government are desperate to hide what is happening from the rest of the world.”

Benny Wenda, the recently elected leader of the United Movement for the Liberation of West Papua (UMLWP), who was granted political asylum in the United Kingdom 16 years ago, accused BP of “supporting an illegal occupation [and]operating in the middle of a genocide”.

British Labour party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, has long supported Wenda and West Papuan independence and endorsed a petition that the UMLWP leader presented to the United Nations last year.

Alex Sobel, a Labour MP and chairman of the British parliament’s all-party group on West Papua, called on BP to pull out of the country until it becomes self-governing.

“BP are operating amid clear human rights abuses. They should learn the lesson of Shell in [Nigeria] and withdraw from West Papua until such time the West Papuans are in control of their land.”

In September, Vanuatu and two other Melanesian nations called on the UN to investigate human right abuses and put West Papua on the decolonisation list of non self-governing territories. Jakarta responded with mass arrests of protestors.

Successive British and Australian governments have ignored the escalating human rights situation in West Papua. Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim nation, is a major trading partner of both countries and a key ally of the West in the war on terror.

The UK has spent over one million pounds since 2014 training Indonesian police units, including Detachment 88, the counter-terrorism unit set up after the 2002 Bali bombings. The British government admitted in July that it has no way of monitoring if British arms sales to Indonesia are being used in West Papua.

Australia has an estimated AUS$10bn of direct investment in Indonesia a third of which is in the mining sector. For years the Anglo-Australian mining giant Rio Tinto has worked closely with the military in West Papua to protect the world’s largest gold mine and second largest copper mine.

Lord Harries said: “I once reminded a senior Indonesian official about his government’s repression in East Timor. He replied that East Timor was of no value to them but the resources of West Papua were highly valuable and they would hold on to them come whatever.”

BP beyond scrutiny

In 2000, BP rebranded itself as an environmental and human rights friendly oil company. Out went the green shield and in came a Helios sun logo and new slogan that it was ‘beyond petroleum’.

Two years later, engineers and construction workers started to develop the Tangguh field in West Papua, which has 14 trillion cubic feet of proven gas reserves underneath Bintuni Bay.

Two unmanned platforms were built in the pristine eco-system, where fishing is the main means of subsistence, to transport the gas 22 miles by subsea pipelines to cooling or liquefaction plants on the south shore at Babo.

Prince Andrew visited Tangguh as the UK’s trade representative just before the first liquefied natural gas (LNG) was shipped for sale in 2009 and the petrodollars started to flow back to BP headquarters in London.

All was looking good for the oil giant until the following year when the Deepwater Horizon offshore oil platform exploded, contaminating the Gulf of Mexico and killing 11 people. To pay off the US$65bn compensation and clean-up bill, BP had to start selling off assets.

The gas project in Bintuni Bay was not on the list. In fact, so important is Tangguh to BP and its partners from China, Japan, and Korea that international banks have funded almost US$4bn to construct a third liquefaction plant and two new offshore platforms by 2020.

The majority of the LNG it produces will be sold to Indonesia, making Tangguh vital to Jakarta’s energy security and its expansion a national strategic infrastructure project.

Resource-rich but remote places such as West Papua are attractive to BP because of tax incentives and a lax regulatory environment compared to the developed world. And the violent stranglehold of military occupation in West Papua, where journalists enter illegally at their peril, puts the oil giant largely beyond scrutiny.

The act of killing

Control of West Papua was established by a brutal invasion where an estimated 30,000 Papuans were killed between 1965 and 1969 by US-backed Indonesian security forces.

The soldiers were fresh from murdering over 500,000 suspected communist sympathisers in their own country, as described in British documentary maker Joshua Oppenheimer’s much lauded film, The Act of Killing.

Indonesian military intelligence then rigged a controversial vote among selected Papuans in 1969, which to its discredit the United Nations went along with.

“The so-called Act of Free Choice which resulted in Indonesia claiming West Papua was a total fraud,” said Lord Harries. “As a British foreign minister once said [in parliament], 1,000 handpicked people were ‘largely coerced’ to agreeing to integration with Indonesia.”

Since the invasion, a policy of ‘Indonesianisation’ through displacement then mass migration has relegated Papuans to little more than a supply of menial labour and a curiosity because of their many tribal cultures – penis gourds and bow and arrows are used to promote the leading coffee chain and bakery in West Papua.

Meanwhile, Jakarta continues to market West Papua to the outside world as an eco-paradise for big spenders who can dive in Raja Ampat or trek the rain forests of the Arfak Mountains. Boutique travels firms also take tourists on human safari where they can be photographed with dancing forest tribesmen.

Even Hollywood is in on the swindle. A Cate Blanchett-narrated documentary, Journey to the South Pacific, on West Papua’s marine environment – told through a happy-go-lucky Melanesian boy and his smiling friends – assures viewers that life for them ‘flourishes’ above the sea when, in truth, they are condemned to poverty, illiteracy and underemployment.

We don’t want another Colombia

“The take over by Indonesia, with control of every aspect of economic and political life, has left its people a minority in their own country, repressed and subjugated,” said Lord Harries.

“Papuans are becoming foreigners and foreigners are becoming Papuans – and it is supported by the World Bank,” said Wenda, who lives in Oxford, where the local council is considering awarding him a ‘freedom of the city’ honour alongside Nelson Mandela. Back in Jakarta, he is considered a terrorist and someone BP has conspicuously avoided.

Critics argue that a truly ethical energy company would never have gone into West Papua. But BP claimed it would operate to the highest corporate social responsibility standards.

[the_ad id=”110084″]It did not want to repeat the public relations disaster of its involvement in Colombia in the late 1990s.

Back then, this reporter exposed how BP, working with ex-SAS private contractors, funded and shared intelligence with the Colombian security forces, who were responsible for ‘cleansing’ any hint of peaceful opposition around the oil fields of Casanare.

Unlike Colombia, West Papua has no foreign-backed and well-armed insurgency but a rag tag group of around 300 poorly trained men from the central highlands whose arsenal includes stolen guns and homemade spears.

BP accepts that the Organisasi Papua Merdeka (OPM) or Free Papua Movement does not operate in the Bintuni Bay region.

The greater threat comes from government security forces, says Yan Christian Warinussy, director of LP3BH, a local human rights organisation who BP asked to train its security guards between 2006 and 2008 as part of its ‘community based’ approach for Tangguh.

Since BP’s arrival, Warinussy said his organisation has logged a marked increase in reported incidents of violence in the Bintuni Bay area associated with disputes between BP security guards, other employees and contractors. The disputes are over land, the environment and domestic violence. “We have data. The increase is 30% to 40%,” he said. By contrast, BP says it has not self-reported any human rights abuse allegations.

There are also labour rights problems inside the BP base, including racism by Indonesian contractors towards Melanesians. Contractors are expected to hire only indigenous people for unskilled labour, 93% for semi-skilled and 12% for skilled jobs.

When it started constructing its base, BP set up what it called the Tangguh Independent Advisory Panel, drawn from former US congressmen and a retired British diplomat. A Melanesian businessman, who ended up working for BP, was added to the mix.

The men – former U.S. Senator Tom Daschle, retired diplomat Gary Klein, and Augustinus Rumansara, a Papuan who chaired the Asian Development Bank – receive a salary for their time advising BP on a range of issues including recruitment. They fly to West Papua for just over a week to meet local power brokers, visit the base camp and model villagers before writing an annual report based on statistics supplied by BP that is published online.

The panel’s latest report and BP’s response to it accepts that the oil company is nowhere near meeting its target of a skilled Papuan workforce by 2029. The current level is just over 50% and the term ‘Papuan’ is not confined to Melanesians but migrants who have been living in the colony for 10 years. Recruitment programmes have all failed, the panel revealed, and after 15 years Melanesians are almost totally absent from higher skilled or supervisory roles.

Spying on the locals

Gardatama Nusantara is the Indonesian private security contractor that manages the locally employed guards around BP’s installations. The company is run by retired Indonesian army and police and works closely with former officers employed by BP’s internal security department, an insider told New Matilda.

This revolving door eases the sharing of intelligence with the military, which has always sought a greater role in protecting the Tangguh gas field and now has one thanks to the expansion of a third liquefaction plant.

Warinussy is also worried about military intelligence (BIN) targeting popular organisations in Bintuni Bay. “Now many people from BIN are in the community dressed like civilians,” he said.

The panel flagged the problem to BP in its December 2015 report. It said there was a “strong view by BIN that public security forces must be more active at Tangguh and in the community… Senior members of BIN were displeased with access of public security to Tangguh and communication with BP. BIN sees a need for greater intelligence and early detection of potential unrest … to avoid conflict. The continuing dispute regarding [villagers]compensation was cited as a source of local anger and a potential threat to Tangguh”.

The panel, which cautioned against intelligence sharing, did not return to West Papua for two years, but its latest report, published in December 2017, heralds a remarkable volte face; one which BP has enthusiastically embraced, much to the delight of the Indonesian police and army.

“Increased intelligence gathering and sharing is critical for detection and early warning of any suspicious activity. Tangguh security should continue to encourage the local community to share information with BP about new arrivals and any unusual or secretive activities to detect any threatening behavior or incendiary language related to Tangguh,” the panel said.

It also recommended that BP security should be “enhanced with more effective weapons to frustrate if not overcome an armed attack”. Pepper sprays, rubber bullets, stun guns, drones and unspecified ‘other devices’ should be given to an ‘elite cadre’ of guards.

2017-TIAP-Report-on-Operations-and-Tangguh-Expansion-ProjectNew Matilda can reveal that since December 2017 matters have escalated even further. Believing this undercover reporter was working for BP, an Indonesian security manager based at Babo revealed that a small garrison of at least 10 well-armed ‘soldiers’ have been stationed inside the base camp since May this year. BP says they are police, and based there to provide a more rapid response to ‘high level security threats’. These new Indonesian security forces have ‘limited exposure’ to the community, the oil company insists.

Benny Wenda, who escaped to the UK from a Papuan prison 20 years ago, called the increasing militarisation of Bintuni Bay a ‘timebomb’. Warinussy agrees with him. The leading Papuan human rights advocate fears militarisation of the gas field will ‘create problems’ similar to those 350 miles away in another part of West Papua, where the US firm Freeport and Anglo-Australian miners Rio Tinto worked closely with the military to protect the world’s largest gold mine and second largest copper mine.

Rio Tinto, however, has recently sold its interest in the Grasberg mine to an Indonesian company.

BIN blames Free Papua rebels (OPM) for its repressive response to social movements around the mines. But there have been reported cases where intelligence officers have planted evidence and used spies to incite violence to justify clamping down on the unarmed independence movement.

As much as 80% of the military’s income comes from the businesses and facilities it protects, creating a culture of extortion and corruption in the public security forces alongside impunity for human rights abuses.

BP says it pays the energy regulator for any non-lethal police and military assistance to avoid accusations of direct aid. But it has no control over what Jakarta does with the revenues.

Since 2010, BP has paid US$670,000 to the police. The company’s latest accounts show US$266,000 cash payments to the police for joint security operations in 2016. There is no similar disclosure about any payments to the military.

Lord Harries points out that whatever funding mechanism for protection BP hides behind in West Papua, the minister responsible for security in the occupied country is a former general who the UN indicted in 2003 for war crimes in East Timor. His political appointment is a shining example of how impunity works in Indonesia, said the peer.

Fifteen years of development failures

The Tangguh Independent Advisory Panel was set up in 2002 by BP’s then chief executive, John Browne, because, he would later admit, past corporate social responsibility efforts were little more than ‘prettying up’ villages.

Ten villages had to be relocated to make way for the BP base in Babo. Brand new wooden huts were built outside the exclusion zone but near the shore, so villagers could continue shrimping and fishing.

Inevitably, the creation of these trophy villages, which raised a few out of their immediate poverty, caused resentment among the many in the rest of Bintuni Bay who live in cramped, wooden housing without electricity and access to clean water.

Tuberculosis, an illness associated with poverty, is on the rise, a health worker in Babo told this undercover reporter. “There are many cases. It is a big problem because many people live in one house without ventilation,” said the source.

The panel had warned about a development gap between the north and south shore since the beginning of BP’s presence in Bintuni Bay. Fifteen years later it said: “Although basic infrastructure, like walkways and jetties, churches and mosques, are improved from a decade ago, there is still little local health care, almost no land transportation (especially in the north shore), minimal education, poor housing and, in many cases, no reliable electricity.” The panel’s 2015 report also concluded that the projects BP had put in place to close the development gap were failures.

Three years on, little had changed. The latest panel report included this devastating finding. “Many of the long continuing issues relating to relations with Papuans remain unresolved. These include claims by local tribes for compensation, delays in providing north shore housing and electricity, recruitment and promotion of Papuan workers.”

The panel suggested that in the absence of any progress on housing by 2018, BP should build a token bridge, building or walkway in a village as a demonstration of “good faith” and compensation for the 15-year “delay”.

God, however, is doing good business in Bintuni Bay, where various Christian groups are fighting for the Melanesian soul. New churches are being erected in the expanding town of Bintuni on the north shore despite the lack of housing in the surrounding villages.

Lord Hannay of Chiswick, a former British diplomat who was on the panel from 2002 to 2009, called the lack of progress in developing the north and south shores ‘depressing’. BP says it is ‘proud’ of its track record in the area.

The oil company and current panel prefer to blame the north and south shore development gap on dysfunction in the local and national government, failing to recognise the possibility that Jakarta has little interest in raising the standard of living of indigenous people and sows instability among its community leaders.

Most of the gas royalties from Tangguh have yet to be released by Jakarta to West Papua and the system of distribution is opaque, prone to corruption and breeds division.

BP has failed to help train Melanesian community leaders in how to manage the royalties for the greater good. It is indicative of a wider inequality in education between Indonesian and Melanesian children in West Papua.

After 15 years, BP has failed to deliver its promise to build a ‘flagship school’. The panel has suggested the oil company quickly constructs a fully functioning one in time for the opening of the new US$4bn liquefaction plant and offshore platforms in 2020.

This general lack of investment cannot be explained only by a lacklustre approach from Jakarta to its troublesome colony.

While Melanesians are drowning in poverty, BP is now swimming in petrodollars; so much so that it is due to pay US$10.5bn in cash to buy Anglo-Australian mining giant BHP’s oil and gas shale interests in the US. Crude prices dropped in 2014 but have soared and are now at US$72 a barrel. BP says it breaks even at US$50.

The failure after 15 years to close the development gap in Bintuni Bay should also be seen in the context that the West Papuan struggle is largely ignored internationally and BP is operating beyond real independent scrutiny because its operation is so remote and the military prevent outsiders from coming in.

BP was therefore able to ignore its original promise to close the development gap. It then waited for Jakarta to approve the Tangguh expansion project in 2016 before making further promises, which it is still failing to honour.

When the gas is gone

Sustainable employment is going to be a big problem for poorly educated and under skilled Melanesian villagers when the gas is gone.

BP has failed to fully upgrade the fishing fleet of Bintuni Bay villages, who still use non-motorised dug-out canoes to shrimp and fish.

Separately, BP promised to ‘empower local people’ through an indigenous sustainable employment programme and points to its flagship enterprise, Subitu – a micro clothing factory in the town of Bintuni, with a retail shop in Sorong – as ‘tangible evidence’ of success.

The BP panel warned that failure here would “reflect badly” on the company. When this undercover reporter visited the factory Indonesians were clearly in management positions and a handful of Melanesian women were carrying out the manual labour.

The sustainability of Subitu in a post-gas economy is highly questionable. The business is kept afloat by orders for work clothing emblazoned with the logos of BP, Tangguh and its international sponsors. The shop in Sorong that sells these items is run by young trendy Indonesians and would not look out of place in central London. But it is unlikely that its line of clothing will become the must have fashion items of impoverished future generations of Melanesians when the gas is gone.

Death by preventable disease

Many of the best Melanesian minds end up working for the multinationals in West Papua. Dr Pascali is one of them. He has spent the last 17 years at BP and was part of the team that conducted the initial base line study of the local population’s health.

Malaria used to affect 24% of the Bintuni Bay population in 2004 but is now down to 7% thanks to BP sponsored health clinics in villages, he told this undercover reporter, who was posing as a doctor.

The energy giant has achieved this, said Pascali, by giving villagers a cheaper Mefloquine generic, while BP employees receive the more expensive Larium brand. “It’s BP policy,” he explained.

Villagers and employees of the energy giant are also screened for HIV, which was initially caused by the transmigration of infected Indonesian sex workers.

Bintuni town is where workers with cash come to drink and pay for sex. Brothels are ‘underground’ and associated with warungs (Indonesian-run food stalls), said Dr Pascali. “Blacks get infected and infect their wives because they don’t wear condoms. She would suspect infidelity if he did.”

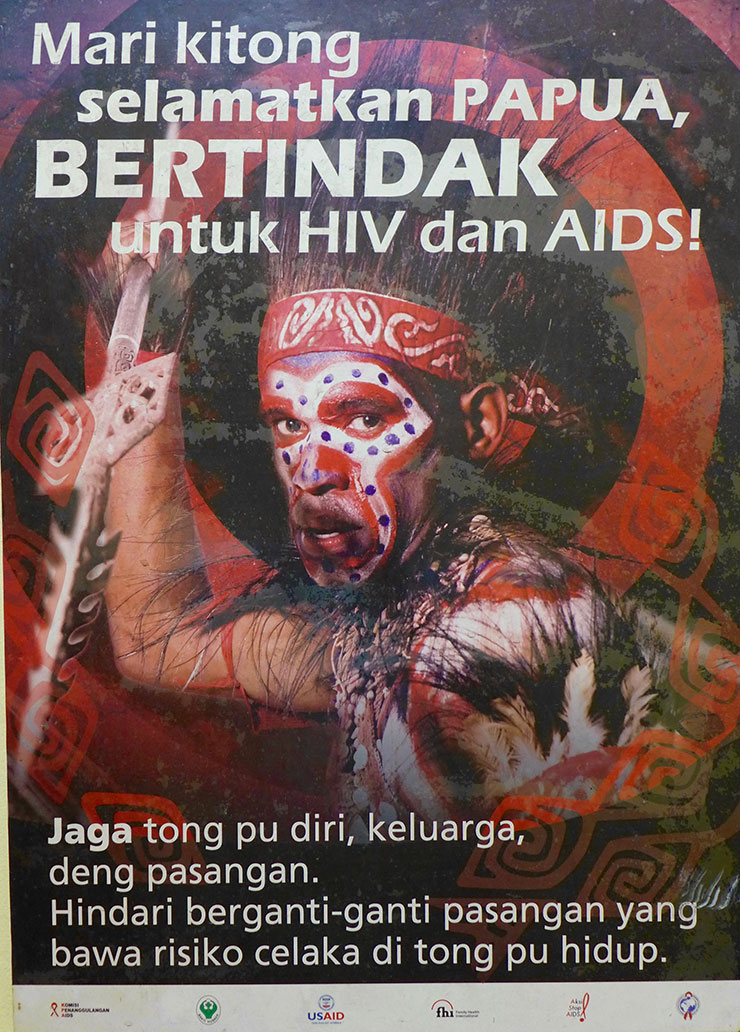

HIV and AIDS awareness posters inexplicably use a picture of a Papuan man in full tribal head gear, further stereotyping the indigenous population as backward savages.

In Babo, a health worker explained how local women had driven out the prostitutes. Nevertheless, “HIV is on the rise and malaria going down,” he said.

A 22-year-old man had died just before this undercover reporter visited the flagship Babo clinic, which serves 3,000 people. It was the first case in 2018 and one of five cases of HIV since 2015.

All visitors to the health clinic are screened for HIV and those infected given Hetero, an Indian-made retroviral drug. This year eight patients are receiving the treatment in a population where women outnumber men.

The Indonesian doctor in charge of the Babo clinic was supportive of BP, who he said had donated an incubator and birthing equipment. But he admitted that the clinic had no electricity during the day.

A health worker took this undercover reporter aside and explained what had transpired. “The generator was destroyed in a fire in February. [The clinic] asked BP to help put out the fire but it refused citing its standard operating procedure. We had to use buckets,” the source recalled.

The Indonesian government provided a new generator in May but when New Matilda visited it had still not been installed because of wrangling with a contractor.

Health records in Babo show there have been seven cases of infant mortality since 2016. The main cause was intrauterine growth restriction and one case of sepsis, which are associated with malnutrition and inadequate health care.

If someone is seriously unwell the clinic in Babo will try to stabilise the patient while others look for a boat to make the three-hour journey across the bay to the town of Bintuni.

By contrast, BP has a chartered private plane to fly its employees out of Babo to a hospital within one hour.

BP maintains that its best security lies in good community relations. But that in turn depends on honouring its development promises and not encouraging locals to spy on each other and share intelligence with a brutal occupying force implicated in human rights abuses.

John Paul Getty, the famously parsimonious oil magnate, gave the most truthful answer to the question many indigenous Papuans ask. Why are we so poor when our country is so rich?

The meek, he said, may well inherit the earth, but not its mineral rights.

* New Matilda sent BP a list of questions. You can read those, and BP’s response, here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.