With the confirmation over the weekend of judge Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court, abortion is now back on the agenda in the United States. And with abortion still ‘illegal’ in NSW and Queensland, and an emboldened religious right in Australia, Dr Danielle Fitzpatrick wonders what that might mean for women’s health closer to home.

On Friday, the US Senate Judiciary Committee voted in favour of appointing Judge Brett Kavanaugh to the US Supreme Court, ending a tumultuous few weeks of speculation amidst sexual assault allegations and growing partisan divisions.

Judge Kavanaugh, a 53-year-old conservative from the US Court of Appeals, will replace Judge Kennedy who announced his retirement from 30 years of service earlier this year.

As the dust settles on one of the most controversial and divisive confirmation proceedings in US history, many are worried that Kavanaugh’s confirmation will disrupt the long-held equilibrium in jurisprudential views within the Supreme Court towards a new, more conservative stance, giving way for re-opened debate on issues long-established as ‘settled law’?

Most controversial is the case of Roe vs Wade which established the right for women to seek safe abortion in the US. Here, I examine what the events in the US could be saying about women’s rights, and public health more broadly, and how we can buffer our health system to protect against changing political tides.

Understanding this controversy and what it could mean for Australia, requires a brief review of US legal history. In 1973, the US Supreme Court, in a landmark decision on the case of Roe vs Wade, established the legality of a woman’s right to have an abortion by establishing that it was encompassed under the Fourteenth Amendment’s declaration of the right to privacy.

This overruled state-based legislation, including a Texan law which prohibited abortion except to save the life of a woman, and became established as national precedent. But a changed balance of views and partisanship within the US Supreme Court could disrupt this long-held precedent, and provide a new avenue to re-open debate on the constitutionality of accessing abortion.

The US Supreme Court has, amongst other powers, the ability to overturn precedent. Whereas up until now supreme court judges in the US have struck a delicate balance in political ideologies, the resignation of Justice Kennedy could provide an opening for President Donald Trump to swing the balance of justices in a more conservative direction.

Brett Kavanaugh could be just that swinging vote. Many Americans are acutely worried what this could mean for women’s right to choose. It raises an important question of what truly is settled law?

Shielded from this debate within Australia, we should, nonetheless, be asking what this anti-liberal march could mean for us. Which political rights have truly become incorporated as “settled law”, and which remain up for re-debate?

As a clinician focussed on health policy, the question for me is even more poignant – where exactly is the line between political ideology and public health drawn?

Many Australians I speak to about this issue, reassure me that the right to safe abortion is protected by law within Australia. But the reality is much more complex than many of us may predict.

In Australia, the laws determining the right to procure legal abortion are determined by state and territory – not Federal – governments and they are subject to vast disparity. Whereas some states clearly establish the legality of abortion (such as Tasmania and Victoria, where abortion is legal up to 16 and 24 weeks respectively), other states (e.g. South Australia) specify that abortion is only permitted to protect the physical or mental health of the woman.

On the other hand, in NSW and Queensland, abortion other than for physical or mental health reasons is still considered a criminal offence. What this means in practice is usually quite different from the written law.

In most settings, women seeking a termination of pregnancy can access safe abortion services during early pregnancy with minimal opposition thanks to careful navigation of the system by doctors and nurses. Health workers address the ambiguity by citing risks to psychological wellbeing or by justifying that the risks to a woman’s life associated with any pregnancy exceed risks in a non-pregnant woman.

It’s a system that (usually) works, but that undoubtedly involves patients and doctors absorbing a level of risk to protect women’s right to choose.

Yet, for public health bodies, the evidence supporting access to safe abortion care is well-established and more than settled. Evidence from the World Health Organisation has consistently demonstrated that rates of abortion remain unchanged across almost all countries irrespective of whether laws recognise abortion as legal or illegal. What does change, however, is the proportion of abortions which are performed in safe, sterile environments and the risk to women of life-threatening complications.

So, is a system that’s not broken, worth fixing at the risk of sparking an uncomfortable and divisive debate? Up until recently, I would have been unsure, but the events unfolding in the US pose the question of how robust our right to health really is.

Instead, we need to ask how we can insulate our health rights from fluctuating and partisan political discourse. One solution could be to unify our disparate state-based laws through federal legislation, providing an additional layer of legislation to protect women’s rights.

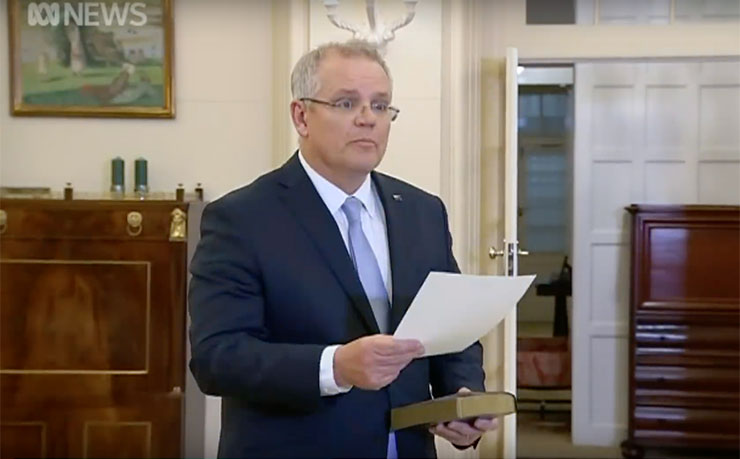

With Scott Morrison as Prime Minister, this is probably even less likely. The events unfolding in the US further suggest that precedent, such as that established by Roe vs Wade, may be insufficient.

Instead, I suggest that we need to transition the discussion from one centred on personal morality and political ideologies, to one that hangs on public health values and evidence-based practice, thereby shielding our health system from changing political tides.

Evidence-based cost-effective public health practice should be protected from political discourse, guided by expert decision and in-line with international recommendations, both of which can serve as domestic justifications to rebut partisan-driven critique.

Of course, deference to bureaucracy comes with risks, and accountability of public health bodies to political leaders through regular review is imperative. Frequent and comprehensive review of health service delivery is essential to ensure that we keep meeting the goals of cost-effective, equitable and high-quality care.

But when services tick all of these boxes, public health bodies should have the power to insist that they are provided for all. It’s a matter of life and death.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.