Rome (Canberra) continues to fiddle while Black Australia burns. Professor Jon Altman weighs in on the ongoing disasters of government policy that have a tight grip on remote living Indigenous people.

In the last month I participated in two workshops. I used what I observed on my latest visit to Arnhem Land and what people were telling me to inform what I presented at the workshops.

The first workshop explored issues around excessive consumption by industrialised societies globally and how this is harming human health and destroying the planet. Workshop participants asked how such ‘consumptogenic’ systems might be regulated for the global good? My job was to provide a case study from my research on consumption by Indigenous people in remote Australia.

The second workshop looked at welfare reform in the last decade in remote Indigenous Australia. In this workshop I looked at how welfare reform by the Australian state after the NT Intervention was creatively destroying the economy and lifeways of groups in Arnhem Land who are looking to live on their lands and off its natural resources.

Here I want to share some of what I said.

BROADLY speaking Indigenous policy in remote Australia is looking to do two things.

The first is to Close the Gaps so that Indigenous Australians can one future day have the same socio-economic status as other Australians. In remote Australia this goal is linked to the project to ‘Develop the North’ via a combination of opening Aboriginal communities and lands to more market capitalism and extraction, purportedly for the improvement of disadvantaged Indigenous peoples and land owners.

While remote-living Indigenous people have economic and social justice rights to vastly improved wellbeing, in such scenarios of future economic equality based on market capitalism, the downsides of what I think of as ‘consumptomania’ are never mentioned.

The second aim of policy is the extreme regulation of Indigenous people and their behaviour, when deemed unacceptable. In a punitive manifestation of neoliberal governmentality, the Australian state, and its nominated agents, are looking to morally restructure Indigenous people to transform them into model citizens: hard-working, individualistic, highly educated, nationally mobile at least in pursuit of work (not alcohol), and materially acquisitive.

This paternalistic project of improvement makes no concessions whatsoever to cultural difference, colonial history of neglect, connection to country, discrimination, and so on.

In the last decade new race-based instruments have been devised to regulate Indigenous people including their forms of expenditure (via income management), forms of working via the Community Development Programme (CDP) and their places of habitation, where they might access basic citizenship services.

All these measures have implications for consumption of market commodities, including food from shops, and of customary non-market goods, including food from the bush.

We have all heard the bad news, year after year, report after report, that the government-imposed project of improvement, called ‘Closing the Gap’ and introduced by Kevin Rudd in 2008, is failing.

Using the government’s own statistics, after 10 years only one target, year 12 attainment, might be on track. I say ‘might’ because ‘attainment’ is open to multiple interpretations: is attainment just about attendance or about gaining useful life skills?

What national and average Closing the Gap figures do not tell us is just how badly the estimated 170,000 Indigenous people in remote and very remote Australia are faring. This region where I focus my work covers 86 per cent of the Australian continent.

What we are seeing in this massive part of Australia according to the latest census are the very lowest employment/population ratios of about 30 per cent for Indigenous adults (against 80% for non-Indigenous adults) and the deepest poverty, more than 50 per cent of people in Indigenous households currently live below the poverty line.

This is also paradoxically where Indigenous people have most land and native title rights, a recent estimate suggests that 43 per cent of the continent has some form of indigenous title; and is dotted with maybe 1000 small Indigenous communities with a total population of 100,000 at most.

Native title rights and interests give people an unusual and generally unregulated right to use natural resources for domestic consumption.

This form of consumption might include hunting kangaroos or feral animals like the estimated 100,000 wild buffalo in Arnhem Land. Such hunting is good for health because the meat is lean and fresh; it is also good for the environment because buffalo eat about 30kg of vegetation a day and are environmentally destructive; and it is good for global cooling because each buffalo emits methane with a carbon equivalent value of about two tonnes per annum.

The legal challenge of gaining native title rights and interests is that claimants must demonstrate continuity of customs and traditions and connection to their claimed country. But in remote Australia, culture and tradition have been identified as a key element of the problem that is exacerbating social dysfunction. (That is unless tradition appears as fine art ‘high culture’ which is imagined to be unrelated to the everyday culture and is a favourite item for consumption by metropolitan elites.)

Hence the project of behavioural modification to eradicate Indigenous cultures that exhibit problematic characteristics, like sharing and a focus on kinship and reciprocity, to be replaced by western culture with its high consumption, individualistic and materially acquisitive characteristics.

Connection to country, at least if it involves living on it, is also deemed highly problematic by the Australian state if one wants to produce western educated, home-owning, properly disciplined neoliberal subjects — terra nulliusis now to be replaced by terra vacua, empty land.

Such empty land would be ripe for resource extraction and capitalist accumulation by dispossession Despite all the talk of mining on Aboriginal land, there are currently very few operating mines on the Indigenous estate. This is imagined as one means to Develop the North, but recent history suggests that the long-term benefits to Aboriginal land owners from such development will be limited.

MUCH of what I describe above in general terms resonates with what I have observed in Arnhem Land where I have visited regularly since the Intervention; and what I hear from Aboriginal people and colleagues working elsewhere in remote Indigenous Australia.

From 2007 to 2012 all communities in Arnhem Land were prescribed under NT Intervention laws. Since 2012, under Stronger Futures laws legislated in force until 2022, the Aboriginal population has continued to be subject to a new hyper-regulatory regime: income management, government-licenced stores, modern slavery-like compulsory work for welfare, enhanced policing, unimaginable levels of electronic and police surveillance, school attendance programs and so on.

The limited availability of mainstream work in this region as elsewhere means that most adults of working age receive their income from the new Community Development Program introduced in 2015. Weekly income is limited to Newstart ($260) for which one must meet a work requirement of five hours a day, five days a week if aged 18-49 years and able-bodied.

Of this paltry income, 50 per cent is quarantined for spending at stores where prices are invariably high, owing to remoteness.

The main aim of such paternalism is to reduce expenditure on tobacco and alcohol which cannot be purchased with the BasicsCard.

Shop managers that I have interviewed tell me that despite steep tax-related price rises (a pack of Winfield blue costs nearly $30) tobacco demand is inelastic and sales have not declined.

Since the year 2000, Noel Pearson has popularised his metaphor ‘welfare poison’. Pearson is referring figuratively to what he sees as the negative impacts of long-term welfare dependence. In Arnhem Land welfare is literally a form of poison because in the name of ‘food security’ people are forced to purchase foods they can afford with low nutritional value from ‘licenced’ stores.

However, paternalistic licencing to allow stores to operate the government-imposed BasicsCard is not undertaken equitably by officials from the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

So one sees large, long-standing, community-owned and operated and mainly Indigenous staffed stores being rigorously regulated, managers argue over-regulated. Such stores are highly visible, as are their accounts.

But small private-sector operators (staffed mainly by temporary visa holders and backpackers) that have been established as the regional economy has been prised open to the free market appear under-regulated, even though they are also ‘licenced’ to operate the BasicsCard.

These private sector operators compete very effectively with community-owned enterprises because they only have a focus on commerce: all the profits they make and most of the wages they pay non-local staff leave the region.

Owing to deep poverty, many people can only purchase relatively cheap and unhealthy takeaway foods that are killing them prematurely from non-communicable diseases, like acute heart and kidney disorders, followed by lung cancer from smoking.

With income management Aboriginal people are being coerced to shop at stores according to the government’s rhetoric for their ‘food security’. Before the introduction of this regime many more people were exercising their ‘food sovereignty’ right to harvest far healthier foods from the bush.

This dramatic transformation has occurred as an unusual form of regional economy that involved a high level of customary activity has been effectively destroyed by the dominant government view that only prioritises engagement in market capitalism — that is largely absent in this region.

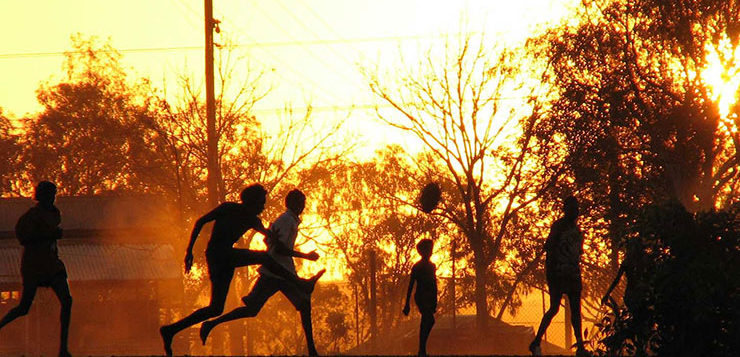

On one hand, we now see the most able-bodied hunters required to work for the dole every week day with their energies directed from what they do best.

On the other hand, the greatly enhanced police presence is resulting simultaneously in people being deprived of their basic equipment for hunting — guns and trucks — regularly impounded because they are unregistered or their users unlicenced.

People are being increasingly isolated from their ancestral lands and their hunting grounds.

Excessive policing, growing poverty, dependency and anomie are seeing criminality escalate with expensive fines for minor misdemeanours further impoverishing people and reducing their ability to purchase either more expensive healthy foods or the means to acquire bush foods.

A virtuous production cycle that until the Intervention saw much ‘bush food consumption’ has been disastrously reversed. Today, we see a vicious cycle where people regularly report hunger while living in rich Australia; people’s health status is declining.

Welfare reform and Indigeneity is indeed a toxic mix, poison, in remote regions like Arnhem Land.

I WANT to end with some more general conclusions.

On the regulation of Indigenous expenditure, we see a perverse policy intervention: the Australian government is committing what are sometimes referred to as Type 1 and Type 2 errors.

The former sees the government looking to regulate Indigenous consumption using the expensive instrument of income management that has cost over $1.2 billion to date, despite no evidence that it makes a difference.

The latter sees an absence of the proper regulation of supply in licences stores evident when stores with names like ‘The Good Food Kitchen’ sell cheap unhealthy take-aways.

In my view the racially-targeted and crude attempts to regulate Indigenous expenditure are unacceptable on social justice grounds.

Two principles as articulated by Guy Standing stand out.

‘The security difference principle’ suggests that a policy is only socially just if it improves the [food]security of the most insecure in society. Income management and work for the dole do not do this.

And ‘the paternalism test’ suggests that a policy like income management would only be socially just if it does not impose controls on some groups that are not imposed on the most-free groups in society.

Paternalistic governmentality in remote Australia is imposing tight regulatory frameworks on some people, even though the justifying ideology suggests that markets should be free and unregulated.

Sociologist Loic Wacquant in Punishing the Poor shows how the carceral state in the USA punishes the poor with criminalisation and imprisonment; the poor there happen to be mainly black.

In Australia, punitive neoliberalism punishes those remote living Aboriginal people who happen to be poor and dependent on the state.

Once again there is a perversity in policy implementation.

Hence in Arnhem Land, people maintain strong vestiges of a hunter-gatherer subjectivity that when combined with deep poverty makes them avid consumers of western commodities that are bad for health (like tobacco that is expensive and fatty, sugary takeaway food that is relatively cheap).

At the same time commodities that might be useful to improve health, like access to guns and trucks essential for modern hunting, are rendered unavailable by a combination of poverty and excessive policing.

Australian democracy that is founded on notions of liberalism needs to be held to account for such travesties.

Long ago in 1859, John Stuart Mill, the doyen of liberals, wrote in On Liberty: “…despotism is a legitimate form of government in dealing with barbarians, providing the end be their improvement and the means justified by actually effecting that end”.

In illiberal Australia today, authoritarian controls over remote living Indigenous people and their behaviour are again viewed as legitimate by the powerful now neoliberal state, even though there is growing evidence from remote Australia that things are getting worse.

I want to end with some suggested antidotes to the toxic mix that has resulted from welfare reform that is targeting many remote-living Aboriginal people and impoverishing them.

First, in my view despotism for some is never legitimate, so people should be treated equally irrespective of their ethnicity or structural circumstances.

Second, the Community Development Programme is a coercive disaster that is far more effective at breaching and penalising the jobless for not complying with excessive requirements than in creating jobs. CDP is further impoverishing people and should be replaced, especially in places where there are no jobs, with unconditional basic income support.

Third, people need to be empowered to find their own solutions to the complex challenges of appropriate development that accord with their aspirations, norms, values, and lifeways. Devolutionary principles of self-government and community control, not big government and centralised control, are needed.

Fourth, the native title of remote living people should be protected to ensure that they benefit from all their rights and interests. There is no point in legally allocating property rights in natural resources valuable for self-provisioning if people are effectively excluded from access to their ancestral lands and the enjoyment of these resources.

Finally, governments should support what has worked in the past to improve people’s diverse culturally-informed views about wellbeing and sense of worth.

While such an approach might not close some imposed ‘closing the gap’ targets, like employment as measured by standard western metrics, it will likely improve other important goals like reducing child mortality and enhancing life expectancy and overall quality of life.

* A version of this article was first published in the Land Rights News.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.