There was a whole lot of fuss during Malcolm Turnbull’s reign as Prime Minister, with nothing much to show for it at the end, writes Ben Eltham. Except for maybe the Liberals being in an even weaker position, which is very hard to imagine.

So, Prime Minister Morrison. Congratulations, I guess, are in order.

I can’t think of too much more to say than that, because on any deeper level the events of last week were a devastating indictment on Australian democracy, and more particularly, our political class.

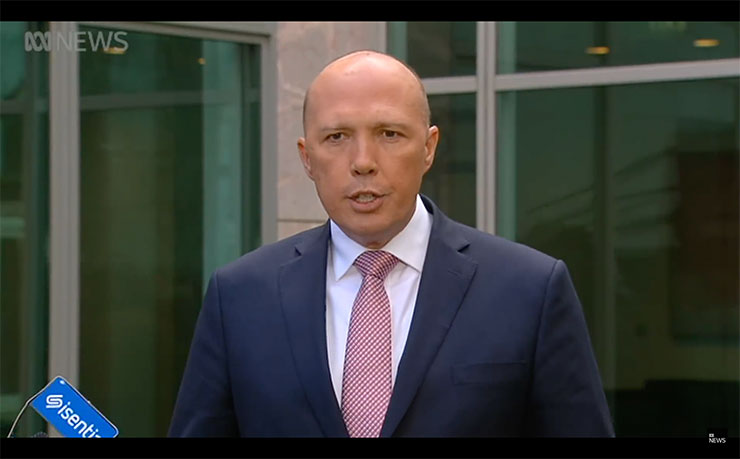

It’s breathtaking, and also a little terrifying, to realise that Australia came within a few Liberal party room votes of seeing Peter Dutton become prime minister. The consequences for Australia of such a victory could hardly be contemplated, but they surely would have presaged dangerous further erosion of civil liberties, the summoning of dark hatreds based on fear and atavism, and possibly even major civil unrest.

As we discovered last week, the insurgents on the right wing of the Liberal Party were far from ruthless in their combinations. Their plot was a disastrous failure, resulting in the ascension of Morrison instead.

It’s a massive relief that Dutton isn’t the new head of Australia’s government, then. But that’s about the best you can say.

The damage last week’s events have done to the Liberal government can scarcely be overstated. The mood amongst school parents when I picked my daughter up from school on Friday afternoon was one of scorn, derision, and outright contempt. One friend I spoke to, who doesn’t follow politics and rarely reads a newspaper, asked simply why voting is still compulsory if our nation’s politicians can be this incompetent. The word that kept coming up was “circus.”

Sadly, the damage is not just to the Liberal party, but to Australian democracy in general.

Weeks like this do harm to the project of democracy that can take years to repair, if indeed there is ever a recovery. When the people we elect act in such a ridiculous manner, with such naked disregard for the electorate, and with such malice and dishonesty towards their own colleagues, it can be no surprise that ordinary voters are disgusted.

Last week we saw a sitting prime minister torn down by his own party. No reason was proffered by the plotters, save the most perfunctory justification of keeping Labor out of power. Voters were not consulted; nor, in any formal manner, were party members. Only 85 politicians got a vote. This is, of course, how Westminster parliamentary democracy works. Which simply proves, if more proof were needed, that the current system is badly broken.

We were saved from a Dutton prime ministership by the incompetence of the challenger and his conspirators. The ineptitude of the rebels was stunning. At no stage did Peter Dutton have the numbers to become leader, as two votes in the party room showed. A small group of men aspired to run a $450 billion government, but they couldn’t even count to 43.

In the end, all that Dutton and his fellow wreckers managed to do was to destroy the leadership of Turnbull. For Tony Abbott, that may have been all that counted. For Dutton, the ashes of defeat will be bitter indeed. But for civil society in Australia, there is well justified cause for relief.

Amidst the devastation, Scott Morrison has risen to become Prime Minister. For this canny and deeply ambitious man, it will be a moment to savour. Morrison has long groomed himself for the job. Charged with a deep well of religious belief, and a streak of political mongrel that in some respects recalls that of Paul Keating, Morrison now has a chance to make his mark.

The challenges he faces as the new leader are stern indeed. The Liberal Party is a smoking ruins today, with half the party room willing to tear down the party’s most popular leader, and with conservative and moderates at each others’ throats.

While Morrison will enjoy a brief period of support from the party room, any unity is likely to be brief. The resentment of the spurned conservatives will smoulder. It is a mistake to say the new Prime Minister can draw on support from the conservatives; he has been widely vilified within the party as a turncoat ever since he threw in his lot with Malcolm Turnbull in 2015.

What can we say about Malcolm Turnbull as prime minister? Unfortunately for Australia, his record is not particularly impressive. When judged against his own lofty rhetoric, his policy achievements are modest.

Malcolm Turnbull made Australia less fair, and more unequal. In economic terms, his signature policies were a series of tax cuts, most of which accrued to big business and wealthy individuals. There is little to be said for these as genuine reforms. They will not make Australia’s economy more competitive, or improve productivity or innovation. They will rapidly increase wealth and income inequality. Skewed markedly towards the top 20 per cent, they will allow the rich to get richer, but leave the lower-middle classes no better off.

The tax cuts will, however, blow a big hole in future federal budgets subtracting tens of billions a year from government revenues. Most remarkably of all, the tax cuts were implemented while the budget was still in deficit. So much for the budget emergency.

In social policy, Turnbull was similarly regressive. It’s true he wasn’t quite a slash-and-burn hacker in the same mould as Abbott and Hockey; with Morrison as Treasurer, government spending has actually been increasing. But most of this spending is going to Defence and national security, while many aspects of the welfare safety net are being starved. Health and education spending are well down on their levels as a share of GDP when Labor left office; $2.2 billion has been cut from universities, billions more from hospitals and schools.

We can agree that Turnbull was the prime minister when Australia finally voted for marriage equality. Exactly how much credit Turnbull can take is a matter for considerable debate. The policy for a marriage plebiscite was imposed on Turnbull by the conservatives on his back bench; the vote itself was a deeply divisive and painful moment for Australian society. Yes, Turnbull got to sign it into law. But the true winners of marriage equality were LGBTQI campaigners.

In some policy areas, Turnbull left Australia a manifestly worse place than he found it. His multi-technology model for the National Broadband Network has been an unmitigated disaster, leaving Australia with a tragically wasted opportunity for a genuine fibre-optic national network. In areas like privacy and data security, he has enthusiastically championed the capture of the entire population’s phone and email metadata, and presided over a bungled Census, the disastrous My Health Record digital health database, and issued hundreds of millions of dollars of false welfare debts through Centrelink. There is an incipient crisis in aged care, with funding not nearly enough to meet demand.

A special mention must go to Turnbull’s colossally destructive failures on the environment. It’s hard to overstate the significance of a prime minister who ended his reign by agreeing to abandon Australia’s Paris commitments – a low-light not even Tony Abbott could muster. The irony was that even though Turnbull capitulated to everything the right-wingers demanded on his National Energy Guarantee, they still moved against him. It wasn’t just carbon emissions either: there were roll-backs of marine parks, approvals to coal mines, and of course the scandal of the $444m grant of federal funds to the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, a dubious charity.

Perhaps Turnbull’s real legacy, the one that will certainly be discussed by future historians, will be his peremptory rejection of the Uluru Statement. This was an act of astonishing high-handedness; a stunning demonstration of the contempt for which he held Indigenous Australia. The rejection was all the more telling because Indigenous affairs is a portfolio of such obvious importance to the past, present and future of Australia. Presented with the outcome of a decade-long process of constitutional and legal reform, Turnbull turned his back on a chance to make history. Posterity will not judge him lightly.

Many of these policies were designed or pursued by Scott Morrison as Treasurer. If, like me, you think policies are ultimately more important the personalities of leaders and the tactics of parties, then this should give the Coalition pause for thought.

Under their most popular leader, Turnbull, the Coalition’s policies were unpopular, and the government was behind in the polls. How will they go now, with the same policies, but with a less popular leader in charge?

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.