Drawing on a loose interpretation of international data, Treasurer Mathias Cormann is once again trying to convince us that corporate tax cuts are a path to “jobs and growth”. The reality is that our companies already have plenty of funds to invest – funds they are presently handing back to shareholders and to overpaid corporate executives, writes Ian McAuley.

“Australia surges to 10th highest average tax rate” read the headline in the Sydney Morning Herald last Wednesday.

The article, written by Eryk Bagshaw and Peter Martin, was about Finance Minister Mathias Cormann’s claim that Australia’s corporate tax rate has “rocketed” in the last decade. Cormann has wheeled out data from Oxford University that he claims supports the Coalition’s case for cutting Australia’s corporate taxes.

Far from “rocketing” upwards, however, in a deal negotiated with the Senate the Turnbull Government has actually cut corporate tax rates for most Australian companies, from 30 per cent to 25 per cent. Only companies with a turnover above $50 million remain on the 30 per cent rate, and Cormann wants to see that rate also brought down to 25 per cent.

Cormann’s point seems to be that because some countries, including Japan, the UK, Russia and Italy, have been cutting corporate tax rates, Australia’s ranking has shifted (to 10th spot) relative to the other 42 “leading global economies” in the Oxford database.

In a splash of hyperbole that is uncharacteristic for such experienced journalists, Bagshaw and Martin write that since 2005 there has been “a worldwide program of slashing taxes”. But when we study the Oxford database (an easily downloaded set of spreadsheets) we see that many countries have left their tax rates just where they were in 2005, and that some have actually raised corporate tax rates.

Even the chart in the SMH article shows that Australia’s tax rate is lower than Germany’s (hardly a struggling economy), and that one of the most aggressive tax cutters has been the UK (hardly a successful economy).

The finding that Australia now occupies 10th place among 43 “leading industrial countries” does seem to suggest that our tax rate is becoming uncompetitive. That is until we look at the selection of countries in the Oxford database, and see that it includes Chile, Indonesia, Greece, Mexico, South Africa and Saudi Arabia. Had the Oxford researchers thrown in a few more resource-rich or struggling countries they could have made our ranking look even worse.

As a general point, established and prosperous countries – so-called “developed” countries – don’t have to use low corporate taxes to compensate for other shortcomings. If a country has good infrastructure, a well-educated workforce, a professional and uncorrupted public service, and reasonably stable and well-crafted economic policies, a country does not have to enter a race to the bottom to attract corporate investment.

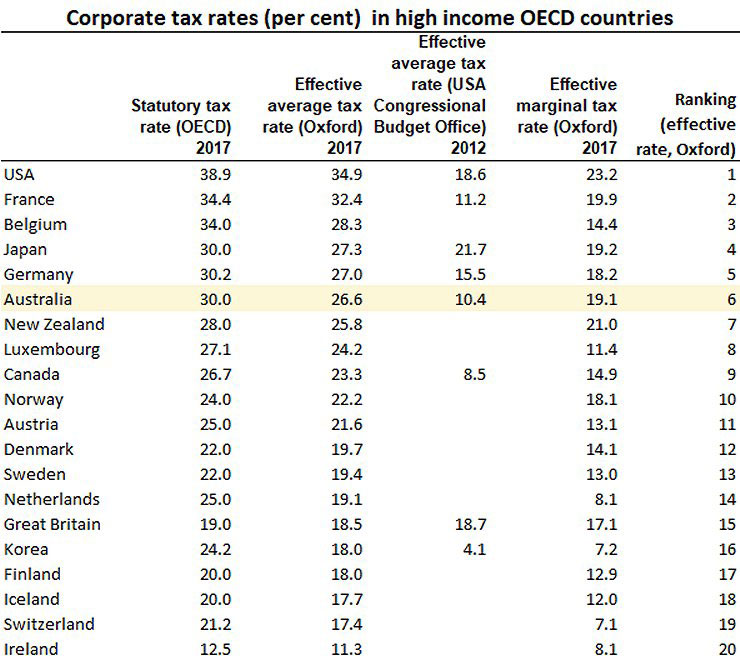

So, using what comparative data is available, I have drawn together three sources of comparative corporate tax rates – from the OECD, from the Oxford project itself, and from the US Congressional Budget Office – to produce the table below. To contain the set to generally comparable countries the table covers the 20 highest-income OECD countries, but not low-income OECD countries such as Chile, Greece and Mexico.

The rates in this table pre-date the Turnbull and Trump tax cuts in Australia and the USA. The effective tax rates incorporate adjustments for tax concessions, mainly depreciation allowances. And the marginal tax rates are those faced by established businesses making new investments.

Whichever way we sort this table – on statutory or effective rates – Australia does appear to be among the higher-taxed developed countries. But it should be noted that we have some reasonably well-performing neighbours in the table, with tax rates that are not much different from ours.

Also, not included in such tables are charges that do not classify as “tax” but which are virtually inescapable, such as employees’ health insurance payments made by corporations in the USA. Trump’s much-heralded tax cuts won’t reduce those levies. They reduce the headline federal rate from 35 per cent to 21 per cent, but state corporate income taxes (currently around an effective rate of six per cent) remain, and a number of concessions have been abolished, including the deductibility of state taxes.

The major omission in this comparison, however, is any mention of Australia’s system of tax imputation, an arrangement shared only with New Zealand. When a company pays a dividend to an Australian shareholder, individual or corporate (e.g. a superannuation fund), the shareholder receives a full credit for the company tax paid.

Data from the Australian Stock Exchange data series shows that in 2017 Australian-listed companies paid out 71 per cent of their earnings as dividends. That means for an Australian investor the effective corporate tax rate, even for an investment in a large company paying the full statutory rate, is only 8.7 per cent (30% * (1 – 0.71)). That puts us down there with the lowest-taxed countries.

Of course, dividend imputation does not apply to foreign investors, and if Australia were a developing country with inadequate internal investment funds, then a bid to attract foreign investors may make sense. But Australians have more than $2.1 trillion in superannuation, and substantial savings outside superannuation. Unfortunately ill-considered tax incentives have encouraged Australians to invest in housing, while shying away from direct share ownership.

We’re misdirecting our savings and letting foreigners buy our best assets. Foreign investment, which is still flowing into Australia, comes with strings attached, including franchise restrictions which relegate Australian subsidiaries to low-value activities, tax minimisation, and of course the need to repatriate profits to foreigners.

Furthermore, as John Freebairn of Melbourne University points out in plain language, a tax cut applied to existing companies would be a windfall benefit to already-established foreign shareholders, while conferring no similar benefit to Australian shareholders, who would receive lower imputation credits.

We need to be better informed on tax policies, but it’s as if the case for corporate tax cuts is so cut-and-dried that it’s a heresy to question it. Claire Connolly (“Ex-ABC Heavyweights weigh in over claims Emma Alberici was censored”), Quentin Dempster (“Has the ABC buckled to PM Malcolm Turnbull by removing critical ‘analysis’ of the claimed benefits of corporate tax cuts?”) and others have commented on the ABC’s reaction to Emma Alberici when she presented a well-researched analysis questioning the need for corporate tax cuts. That was a clear case of gauche and heavy-handed censorship following (and possibly resulting from) government complaints.

Also within the ABC there seems to be subtle censorship at work, such as the easy run presenters on the influential ABC RN Breakfast give to Cormann and other Coalition politicians (as a regular listener to Breakfast I have never heard the presenters raise the issue of imputation when there is discussion of tax cuts).

There is no shortage of investable funds in Australia. We don’t need to go begging foreigners to help us out. But we do seem to have a shortage of investment opportunities. Corporate profits have been on a long-term upward trend. Companies, when they make a profit (and once they have paid generous salaries to executives and board members and made a few donations to political parties) are handing most of their profit back to shareholders. As I mentioned companies, are now paying out 71 per cent of earnings as dividends, a proportion that has been creeping up over the last 12 years (in 2006 the payout was only 55 per cent).

When corporate managers have plenty of cash, but cannot see anything to do with it, it’s a pretty sure sign that there are structural problems or public policy failures in the Australian economy.

Perhaps our poor transport infrastructure, our slow internet, our slipping education standards, the growing perception of corruption in our institutions, a dysfunctional energy policy, and National Party-induced political instability, are all playing their parts in rendering Australia as a country that has nothing to offer other than the carrot of tax cuts.

If so, it’s a dismal picture.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.