The Coalition’s new energy plan fails on every dimension: energy, environment and politics, writes Ben Eltham. The only winner is Tony Abbott.

There are three ways to examine Malcolm Turnbull’s new energy policy, unveiled yesterday. What does it mean for Australia’s energy system? What does it mean for the environment? And what does it mean politically?

Let’s examine each of these dimensions in turn.

The National Energy Guarantee: how will it work?

The new plan, already christened the ‘NEG’, is the Turnbull government’s long awaited response to the review of the energy system carried out by Chief Scientist Alan Finkel.

The centrepiece of Finkel’s plan was his idea for a Clean Energy target. That proved a big problem for the Liberal backbench, probably because it had the word “clean” in it. So the CET has been junked. Instead, the Coalition has come up with a complex new policy that it’s calling the National Energy Guarantee, or NEG.

The NEG has two main aspects: a “reliability guarantee” and an “emissions guarantee”.

First, there will be a new policy to ensure the grid has enough “dispatchable” power: in other words, enough supply, ready to be switched on at a moment’s notice, to ensure that the lights don’t go out.

To do this, the government wants to create a new regulation, in which electricity retailers will be forced to ensure that a set percentage of their supply is purchased from “ready-to-use sources such as coal, gas, pumped hydro and batteries”.

Second, there will be an “emissions guarantee”, which, and I quote, “will be set to contribute to Australia’s international commitments. The level of the guarantee will be determined by the Commonwealth and enforced by the AER”. In other words, the government argues this scheme will ensure Australia’s Paris commitments. As we’ll see below, that’s not true.

With emissions reductions targets and the ability to trade credits, including internationally, the emissions guarantee looks very much like a jury-rigged emissions intensity scheme. Analysts are pointing out that this simply represents another form of carbon pricing. Presumably, Josh Frydenberg didn’t explain it like this to the Coalition backbench.

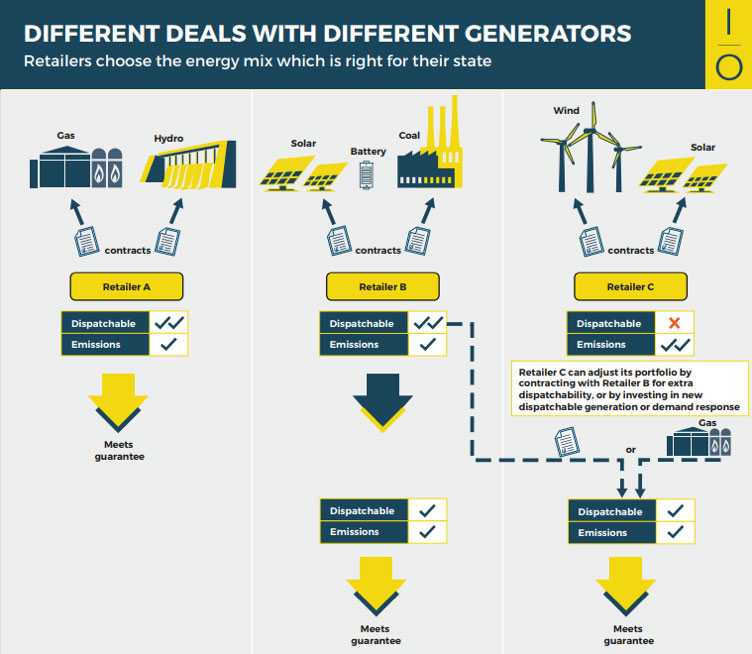

One of the really interesting aspects of the scheme is that it also appears to allow trading of the “reliability” aspect of retailer requirements. The mechanism will probably take the form of so-called “cap contracts” in which retailers enter into contracts for dispatchable power, up to a certain percentage of their forecast peak load.

This may also enable trading of credits for dispatchable power. To keep the carbon warriors happy, the government has decided to define coal power plants as reliable (despite the evidence of recent years, in which coal plants have been decidedly unreliable). A diagram on page 4 of the government’s glossy brochure ‘Powering Forward’ seems to bear that out. The only problem with this, as John Quiggin points out today, is that coal isn’t dispatchable.

If the new scheme does allow for trading of credits liked to coal generation, the result will be a market in subsidies for dirty energy: “dirty energy credits”, you might say.

The government claims the new policy will deliver savings of perhaps $115 a year by 2020. That seems heroic. Prices are rising by 20 per cent annually in some states right now. Given the average household electricity bill is now close to $2,000 a year, the true effect of the new scheme may simply be to lock in high prices at their current levels.

Another aspect of the plan worth discussing is the power it gives to the big energy companies like AGL and Origin. The vertically-integrated ‘gentailers’ are already the most powerful players in Australia’s energy system, as AGL graphically demonstrated by staring down the government’s calls to keep the Liddell power plant in New South Wales open. The new policy, which does nothing to reform Australia’s dysfunctional National Electricity Market rules, will merely entrench the market dominance of this oligopoly. AGL, in particular, has a big portfolio of dispatchable and renewable energy, and will be well placed to benefit from the new scheme.

And that highlights another problem of the new policy: it does little to accelerate investment in renewable energy, which is now the cheapest form of new electricity generation. Government estimates suggest that renewable energy could well plateau under the new scheme, although we can’t really be sure, because the modelling hasn’t been done.

And that highlights another problem of the new policy: it does little to accelerate investment in renewable energy, which is now the cheapest form of new electricity generation. Government estimates suggest that renewable energy could well plateau under the new scheme, although we can’t really be sure, because the modelling hasn’t been done.

With remarkable chutzpah, the government is claiming this is as a positive: arguing that the new policy removes all the old subsidies to renewables, and will therefore deliver cheaper electricity as a result.

As usual when it comes to energy policy, this claim is somewhere between a distortion and an outright lie. There will still be subsidies in the new policy: subsidies are implied by the two new guarantees. There are also vast subsidies baked into the structure of the National Electricity Market, due to the “gold plating” of network charges for the construction of unnecessary poles and wires. According to the ACCC, network costs are the biggest component of recent price rises. But nothing has been done to address these.

And, of course, there is the biggest hidden subsidy of all: the subsidy of cost-free pollution for fossil fuel generators, after the abolition of pollution permits in 2014.

Because of the furphy of “no subsidies”, the new policy will have no replacement for the Renewable Energy Target, scheduled to end in 2020. This is dumb policy. The RET has been the only successful Australian energy policy of the past two decades, despite the government’s attempts to destroy it in 2013 and 2014. By providing a legislated target of renewable energy supply, the RET has catalysed most of the new energy supply delivered to the grid in the past decade.

With nothing to replace the RET, there is no legislated trajectory for Australian energy over coming decades; instead, emissions reductions will be again be subject to the extreme political uncertainty of recent years. That doesn’t bode well for investment.

A plan beyond 2030 is required for energy investment. Much faster decarbonisation is also needed. The NEG provides neither.

A NEGative for the environment

When it comes to the environment, the NEG is bad, but perhaps not as bad as it could have been.

This is surprising. Considering how toxic the very idea of reducing carbon emissions has become for the right wing of the Liberal and National parties, few would have placed too much faith in the government’s commitment to Australia’s Paris climate change commitments.

But it is the case that the NEG contains an “emissions guarantee”, and on first glance, it does look as though the scheme could offer a credible pathway to reducing emissions. Even Alan Finkel seems to think so.

But that doesn’t mean the NEG is good enough. The emissions reduction target for the new emissions guarantee will be set at 26-28 per cent of 2005 emissions levels by 2030.

The problem is that reducing the National Electricity Market’s emissions by only 26-28 per cent is not consistent with Australia’s Paris commitments.

The Paris treaty reduction of 26-28 per cent is for the Australian economy as a whole; all credible assessments of Australia’s emissions reduction task tell us that the energy market will need reductions of something like 45 per cent or higher, in order for Australia to meet our overall obligations. In the long term, the only credible policy is complete decarbonisation: the Climate Change Authority, in its special review on how to meet the Paris target, concluded that the electricity sector’s emissions intensity had to get to zero “well before 2050.”

Quite obviously, the NEG won’t deliver this. It can’t. It’s completely silent about any target beyond 2030, and the 2030 targets are too low.

This also means the NEG is a costly policy for the rest of the Australian economy. The electricity sector is actually the easiest place to decarbonise: wind and solar power have made astonishing strides in recent years, and are getting cheaper all the time. In contrast, the agriculture and transport sectors are still a long way off similar transformations.

In summary, the NEG is a fail on environmental policy. It’s a simple as that.

Political failure

But the real failure of this policy is political. That’s because it won’t solve Malcolm Turnbull’s energy headaches.

The Coalition has consistently found energy policy difficult, not without reason. Energy is difficult: it’s a wicked problem, as the nerds like to say, a complex system with many moving parts.

For instance: the government will need the agreement of the states and territories, who have increasingly gone their own way on energy in recent years. The Coalition spent much of 2016 beating up state Labor governments on energy, especially South Australia’s, which it wrongly blamed for the September 2016 blackout (let’s remind ourselves one more time: the blackout was caused by a storm knocking over transmission lines). Three of the four states in the National Electricity Market have ALP governments, which doesn’t suggest the negotiations will be easy.

The Opposition does not look likely to help either. The Labor Party has been bruised and battered by a decade of cynical attacks from the Coalition on climate. At no point since 2009 has the Coalition offered bipartisanship. Under Julia Gillard, a Labor government implemented a comprehensive carbon tax and emissions cap, at very low cost to consumers, while the economy continued to grow. Labor got very little credit for this in office: in fact, Gillard’s supposedly broken promise on carbon pricing came to hang like a millstone around her neck.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that Labor is in no mood to offer the government any political cover for a third-best scheme that won’t meet Australia’s Paris commitments. Labor has potent political reasons to make this as difficult for Malcolm Turnbull as possible.

But the biggest problem for the Prime Minister is that the government’s internal political imperatives and those of the community are wildly out of sync.

But the biggest problem for the Prime Minister is that the government’s internal political imperatives and those of the community are wildly out of sync.

The Liberal Party, as we know, has grown deeply suspicious of the very idea of climate change, with a large section of the backbench hostile to the science of global warming. Energy policy has become a key battleground of the never-ending culture war. For movement conservatives like Tony Abbott and Craig Kelly, opposition to action on climate change has become something of a talisman, a symbol of their true blue conservatism and their credentials as hard-liners and keepers of the Liberal flame.

The majority of voters beg to differ. Renewable energy is popular: remarkably popular, if the opinion polls are to be believed. A recent Essential poll found voters favoured continuing renewable energy subsidies by a whopping 40-point margin – 63-23 per cent. The poll found an amazing 70 per cent of Liberal voters favoured the Clean Energy Target: the very thing that Turnbull has now ruled out.

Figures like this suggest the NEG will be unpopular. Once again, Turnbull has been forced into a disastrous blunder in order to retain the support of his backbench.

So there you have it: the NEG is bad for the energy system, bad for the environment, and bad for the Coalition’s chances for re-election.

It is, however, a win for Tony Abbott, who is once again getting pretty much everything he wants.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.