Everyone has a role in keeping the bastards honest, particularly the bastards fighting marriage equality. Ben Eltham explains.

In nearly a decade covering politics for New Matilda, I’ve seen plenty of perfidy, mendacity and deceit. Labor’s leadership saga springs to mind. ‘The Real Julia’. Gillard’s decision to cut welfare payments to single parents. The Rudd-Gillard years were chock full of lies and stupidity, and then we elected Tony Abbott. So we got Operation Sovereign Borders. The 2014 budget. Compulsory meta-data retention. Robo-debt. I could go on.

But even accounting for all that, the decision to hold a voluntary, non-binding marriage plebiscite by post has got to be one of the dumbest and nastiest political manoeuvres Australia has seen in a very long time.

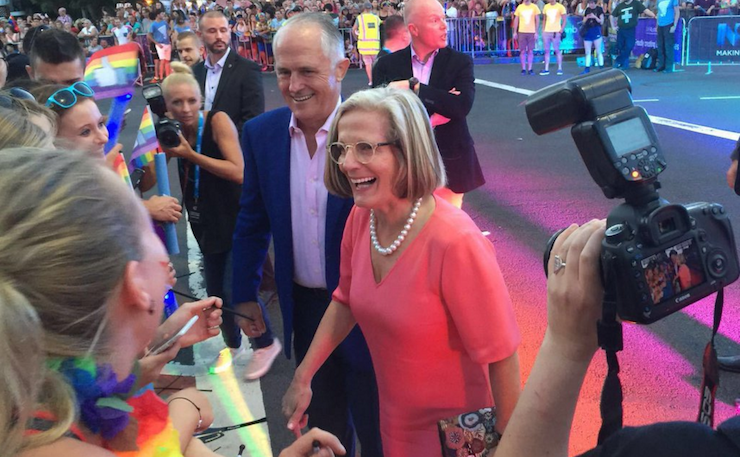

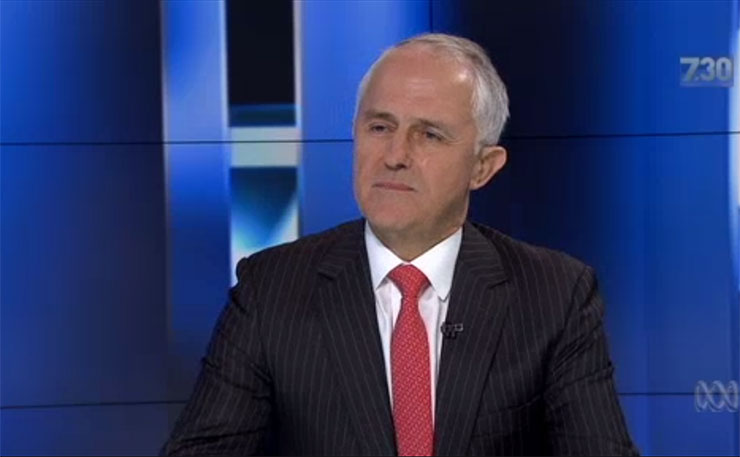

The sheer dishonesty of the measure is hard to fathom. We all know Malcolm Turnbull supports same-sex marriage: he’s told us so, many times. We all know this is a measure designed entirely to keep his party from splitting along ideological lines. We know that the result of the plebiscite will not make any difference to the way most parliamentarians vote on the issue, the next time they do bother to vote. And we all know that a postal plebiscite is a deeply flawed electoral instrument.

But none of this makes any difference: we’re getting a marriage plebiscite anyway. As Chris Graham points out, the result will almost certainly be a long and vicious campaign, in which the main losers will be same-sex families, not to mention the institutions of Australia’s fraying democracy.

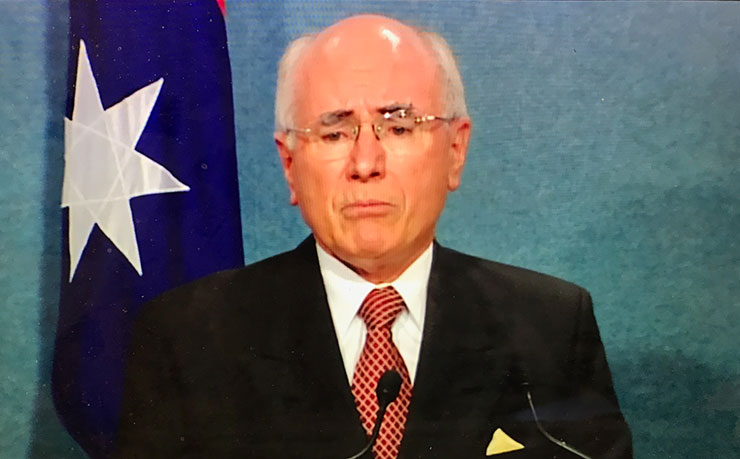

The tortuous history of same-sex marriage in this country is exhausting, but it’s worth explaining a little about how we got to here. The current Marriage Act, amended in 2004 (and passed with bipartisan support by both Labor and the Coalition) outlaws marriage between Australians of the same sex; it also removes recognition of same-sex couples wed in other countries. The law is the one responsible for that nasty little speech you hear marriage celebrants read out at weddings.

Ever since, both major parties have tied themselves in knots on the issue. Labor had six years from 2007 to change the law. It failed to do so, in large part because of the diehard opposition of religious conservatives in the party’s right. The Coalition has had four years since 2013 to change the law. It has failed to do so, in large part because of the diehard opposition of religious conservatives in the party’s right.

Tony Abbott, of course, has always opposed same-sex marriage, and did everything he could while prime minister to derail the debate. That was the origin of the ludicrous plebiscite idea. Abbott knew that a plebiscite was divisive and unpopular, and that it could therefore be used as a tactic to delay marriage equality itself. When Turnbull deposed him in 2015, he cut a deal with conservatives on the issue: he would keep the plebiscite as a policy, and commit to not bringing a free vote on marriage to the floor of the parliament.

And that remains the government’s policy, despite all the internal disunity within the Liberal Party. As a result, the government is pushing ahead with the postal plebiscite.

In principle, asking every Australian what they think about a contentious social issue is a good idea. Australian voters have precious few opportunities to directly have their say on important issues. There are sound arguments to suggest we should have more plebiscites and referenda, for reasons that are as old as democracy itself.

But it should be obvious by now why this particular postal plebiscite is a shabby form of participatory democracy.

Voters won’t even get to see the language of the bill that Parliament will eventually vote on. And, even should the majority of voters approve the plebiscite, there is nothing stopping Parliamentarians from disregarding them.

As many have pointed out, the technology of postal voting is likely to be mystifying for younger voters. A voluntary postal vote will skew the result in favour of older and more conservative voters.

There are genuine technical questions to be answered. What is the question to be asked? What is the process for counting votes? What electoral laws will apply? Why is the Australian Bureau of Statistics handling it, rather than the Electoral Commission?

The legal basis of such a plebiscite is also shaky. Does the ABS have the legal right to hold a ballot of this nature? And can it proceed without an appropriation? With a High Court challenge in the works, the postal plebiscite may not even happen.

But if it does, marriage equality campaigners and the broader progressive left will need to come to a decision about the plebiscite, and quickly.

There has already been talk of a boycott of the poll, including by former High Court judge Michael Kirby. “I think the less said about this irregular and unscientific polling the better,” Kirby told the ABC this morning. “I’m not going to take any part in it whatsoever.”

Many may well agree with Kirby, and withhold their vote. But a plebiscite boycott holds genuine peril for the progressive cause.

As respected psephologist Kevin Bonham points out today, a boycott will almost certainly fail. Given that the poll is voluntary, we don’t know what a ‘good’ turnout figure really means. Bonham argues that a boycott “would only have the effect of watering down the yes vote without affecting turnout enough to do the result’s credibility any further harm”. Even if turnout is below 50 per cent, a defeated plebiscite will almost certainly acquire an aura of democratic legitimacy simply by dent of the fact that it was held.

In an election likely to be marred by vicious attacks on LGBTIQ Australians, a boycott will only play into the hands of conservative campaigners like Lyle Shelton. Ask yourself what the opponents of marriage equality want. They want the plebiscite to fail.

The only alternative is for equality advocates – and for everyone who believes in a just and fair Australia – to fight for the plebiscite, and win.

It will be a tough campaign. Historically, referenda have more often been voted down in Australia. The advantage in votes such as this is generally with the ‘no’ side, which can reap the benefits of fear and confusion, while the ‘yes’ proponents must mount positive arguments for change. While this is a passionate issue for many in the community, the voluntary nature of the vote makes it that much more difficult for the ‘yes’ campaign. Negative campaigning can be very successful in suppressing the vote, by making citizens disgusted with the whole process.

And the ‘no’ campaign have one of the best negative campaigners in the business on their side: Tony Abbott. Abbott well remembers the republic referendum of 1999. We should expect a similar playback of fear, loathing and confusion.

But this is the political reality that progressives must confront.

I wish this plebiscite were not happening. It is dishonest and cruel. But now that it is happening, all who wish for justice in Australia must make their best efforts to win it.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.