This is the third feature in Ben Eltham’s 2017 investigation into Centrelink’s robo-debt program. The first article in the series was published in January, and the second article in March.

Centrelink’s sprawling data-matching empire is opaque, error-prone and almost completely impossible to understand, writes Ben Eltham. And it’s expanding across government programs and agencies.

Victoria Legal Aid’s Dan Nicholson has a good story about the Department of Human Services and its sprawling and opaque bureaucracy. “I guess I would characterise it as an extraordinary lack of transparency,” he told New Matilda.

You could also call it the “Showdown at the Louisa Lawson Building”.

Lawyers at the Victorian legal aid agency wanted to get a copy of Centrelink’s robo-debt algorithm.

If you’re one of millions of Australians who have ever had to deal with Centrelink, you’ve probably heard of robo-debt. The error-prone robot Centrelink has been using to issue tens of thousands of debt notices to ordinary Australians has featured prominently in media coverage since late December.

The experience for individuals was often shattering.

I spoke to one Centrelink robo-debt recipient in December. As ‘Sally’ told me, on the condition of anonymity:

For about two weeks, I was struggling with some pretty serious anxiety as a result of daily automated phone messages and texts telling me I owed a debt. Some did not even identify themselves.

After a while, I typed the debt collectors’ name into a Google search, assuming it was some sort of phishing scam and found others saying it was on behalf of Centrelink. I called Centrelink, who confirmed that I had a debt and needed to pay the collectors directly as it was now out of their hands.

The problems all seemed to trace back to a data matching system that was inherently flawed.

As a source inside Centrelink told me in December:

“… the earnings might be spot on and recorded correctly, but the automated system is not going to be able to reconcile all of those instances with a data match. [It] is inevitably going to end in a letter, even though the calculations during the time on benefits were likely correct.”

Robo-debt started small, but it ramped up very quickly. Although it officially began in July last year, the robo-debt program didn’t get going in earnest until September. By December, 20,000 robo-notices were being sent out each week. The government expects to send out nearly 1.7 million notices in the coming three years.

As the notices started flowing, recipients started getting issued with crippling debts. Their benefits were also being cut off. Desperate people besieged welfare agencies around the nation.

As the notices started flowing, recipients started getting issued with crippling debts. Their benefits were also being cut off. Desperate people besieged welfare agencies around the nation.

People issued with debts found it almost impossible to understand or argue their case. Unable to navigate the usability maze of the federal government’s MyGov website, or get through on Centrelink’s dysfunctional phone lines (there were 42 million unanswered calls in 10 months), clients started flooding into welfare providers looking for help.

By January, the program was in full swing. Debt collectors were actively pursuing at least 6,600 welfare recipients who were later found to have no debts outstanding. Local MPs such as Andrew Wilkie started to hear about it too, as panicked constituents contacted their federal members. Such was the impact in Tasmania, the state’s welfare agencies created a disaster relief fund to deal with it, essentially declaring a public emergency.

By February, an Ombudsman’s investigation had been announced and a Senate Inquiry hastily instituted. By April, Victoria Legal Aid was representing one of the welfare recipients caught in Centrelink’s vast new dragnet.

The showdown at the Louisa Lawson Building

Victoria Legal Aid requested access to the so-called ‘Program Protocol’ – the technical document, issued by the department of Human Services, that describes the operation of the robo-debt algorithm.

“We wrote and the Minister declined to provide us any of the documents,” Nicholson told us in a phone interview. “We then noticed that the Protocol, according to the Government Gazette, should have been available in Canberra.”

Lawyers and activists wanted to see the Protocol because they couldn’t understand how Centrelink was getting it so wrong. They hoped the Protocol would uncover crucial information detailing exactly what the Department of Human Services was doing with its data matching, and what sorts of data Centrelink was trying to match up. After all, Victoria Legal Aid was representing clients appealing Centrelink decisions issued through the robo-debt program.

But looking for the algorithm proved much harder than anyone anticipated.

On the face of things, it should have been a simple matter of asking the Department of Human Services. The DHS had even issued a public notice in the Australian Government Gazette in August last year, explaining that it was abiding by guidelines from the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner.

The robo-debt controversy has placed Australia’s Information Commissioner, Timothy Pilgrim, in a fascinating position. The Information Commissioner exists as an independent statutory agency within the Attorney-General’s Department. The agency is a regulator with legal powers to investigate breaches of the Privacy Act. It also enjoys special legal responsibilities in regards to government data matching. Government agencies like Centrelink are required to comply with a set of data matching guidelines, one of which is that it should publish a written protocol of the data matching program.

Given that, you would have thought that the protocols would be available on a DHS web page. But they were not online.

The snippet in the Government Gazette had noted that a copy of the protocol was available on request from the “Case Selection Section” on Level 2 of the Louisa Lawson Building, the Department’s $225 million neo-postmodernist office building in Cowlishaw Street, Greenway. So that’s where the legal aid laywers went next.

But when Victoria Legal Aid rocked up to the foyer of the Louisa Lawson Building, they were politely told they could not have the document. They weren’t allowed up to Level 2.

“Level 2 of the Louisa Lawson Building is not accessible to the public, nor is it possible to request access to Level 2 from the Ground Floor of the Building,” they wrote in their submission to the Senate Inquiry on robo-debt. The luckless lawyers were told that “only the Director of the Section could authorise access to the document, and the Director was not available”.

Someone would be in contact, they were told. But no-one ever did contact them back. “There was no subsequent communication from any staff of the Department regarding access to the Program Protocol,” they wrote in their submission.

As a journalist, I found getting access to these documents just as difficult.

New Matilda first contacted the Department of Human Services formally requesting a copy of the data-matching protocol on January 8 this year. On January 13, I received an email telling me that the Department was “considering the matter.”

I waited a fortnight, then issued a Freedom of Information request. By mid-May, nothing had been forthcoming, despite the Senate Inquiry beginning and holding public hearings around the country.

Then, on May 17, I received an official “communication” from the DHS freedom of information team. “Although the department is deemed to have refused your request by operation of the FOI Act, we are nevertheless working to provide you with a decision as soon as possible,” they wrote.

It would seem as though my FOI request had been denied. “Please provide your BSB and Account Number so that the department can issue a refund of the charges paid by you,” the email concluded.

But the protocol had already been released – the day before, in fact. On May 16, Information Commissioner Timothy Pilgrim had already disclosed the protocol in a letter responding to Nick Xenophon Team Senator Skye Kokoschke-Moore. Kokoschke-Moore had written to Pilgrim in April, after hearing about the showdown in the foyer of the Louisa Lawson Building.

Sure enough, on May 22 the DHS emailed me back with a copy of the mysterious protocol.

The irony of the wild goose chase? It was the wrong protocol. Centrelink had been relying on a separate protocol, originally written way back in 2004. Centrelink hadn’t updated the protocol before embarking on the dragnet in the second half of 2016; the most recent update is dated May 2017 and was not in place before April. The Department only published the 2004 and 2017 protocols on May 30 this year, in an unannounced update to the DHS website.

The DHS has quietly updated its data-matching protocols page, as of yesterday https://t.co/UbL6sW33vu pic.twitter.com/nMK8TsrndP

— Ben Eltham (@beneltham) May 31, 2017

What the robo-debt protocols tell us

What of the Protocol itself? What does it tell us about what Centrelink is doing?

The answer, for those who know how to read such documents, is quite a lot. And what it reveals is a Department with fundamental problems in the way it designs and manages its data-driven compliance systems.

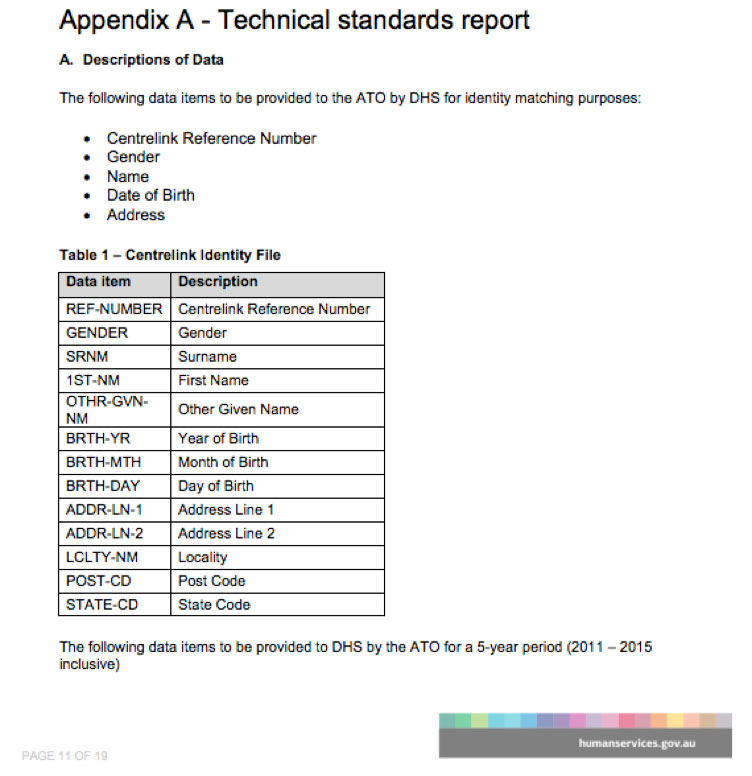

Take the Protocol for the Non-Employment Income Data Matching Program – the very document refused to Victoria Legal Aid in the foyer of the Louisa Lawson Building.

Reading the NDEIM Protocol is a dizzying experience. It’s a glimpse into the inside of the Panopticon. There, in long tables, are all the database fields returned by Centrelink and the ATO when they match your data.

In its section on “Matching Techniques”, the Protocol states that “Information is extracted from the DHS Enterprise Data Warehouse for both current and the target financial years” and that “algorithms are applied to this data to calculate totals for each financial year required.”

There should be nothing wrong with this. The problems appear to come when Centrelink doesn’t return detailed fortnightly data about a given year’s earnings. Then, as we know from the Ombudsman’s Report, it just averages. In other words, it deliberately calculates an error.

If you want a real insight into the design mentality of the robo-debt algorithm, the “risks” section of the Protocol is telling. This is meant to be the section where the program designers anticipate possible issues that might threaten the integrity of their roll out.

But what risks does the NDEIM protocol identify? Very few. The risks section states blithely that:

DHS Customers will be provided with the opportunity to verify the accuracy of the information before any compliance action is taken.

Once again, the blanket assumption is simply that welfare recipients will be able to correct any issues.

There is no discussion in the risks section on risks to privacy.

As one data scientist that looked at the protocol told New Matilda, “this was, in reality, a massively risky project.”

The data scientist added that the protocol should have included at least some reference to the confidence level of the matched data. “The protocol should state the method used to determine non-compliance as well as the level of non-compliance that would be used to determine inclusion in the program,” the analyst told us. But it doesn’t. Instead, human supervision was removed.

The data scientist added that the protocol should have included at least some reference to the confidence level of the matched data. “The protocol should state the method used to determine non-compliance as well as the level of non-compliance that would be used to determine inclusion in the program,” the analyst told us. But it doesn’t. Instead, human supervision was removed.

Comparing past and present program protocols is also very instructive. A careful reading of the 2004 Program Protocol suggests that the robo-debt dragnet designed in 2016 is no longer consistent with the old protocol.

On page 10 of the 2004 document, for instance, the protocol states that:

“Before commencing the review, Centrelink staff will check the customer’s record to determine if the discrepancy can be explained. Where the check is unable to explain the discrepancy, the customer will be contacted by letter. This letter advises the customer that Centrelink has received information from the ATO indicating they may have commenced employment that may not have been declared, or may have been under-declared, to Centrelink.”

By 2016, this had changed. As anyone who’s followed the robo-debt program knows, Centrelink staff didn’t check the customer’s record before issuing a letter.

In fact, the whole point of the robo-debt roll out was to make the sending out of letters after a data match automatic. Centrelink then ramped up on the shakedown, by allowing debt collectors to follow up on the letters – for a 10 per cent bonus.

In a tacit admission of this, the May 2017 Program Protocol has been subtly updated with a different wording. Instead of checking the customers record, the new document states that:

“Before commencing the reviews, DHS staff check the output of the matching and assess the performance and accuracy of the matching process. For the reviews that commence, the recipient is contacted by letter which provides the recipient the employment information that DHS has received from the ATO and requests them to clarify this information online.”

It’s a wording that omits any specific human intervention for each debt letter. Instead, staff are merely checking on “the output of the matching process” – the results after someone presses the button on the output of an Excel macro.

Centrelink had changed the rules. But they continued to insist nothing had changed. The Department of Human Services only published the 2017 update to the data matching protocol on May 30. Centrelink’s updated Non-Employment Income Data Matching protocol is scheduled to go into operation only later this year.

When is an error not an error? When it’s a clarification

There was a revealing moment on the last day of the Senate Inquiry hearings, when Labor Senator Murray Watt asked Secretary Kathryn Campbell about Centrelink’s error rates.

“So there are 10,000 – what do we call them?” Watt responded.

“Initial clarification letters,” Campbell responded, with a thin smile.

It was all very jolly and jovial, as the Brigadier-Secretary with a $731,000 salary hopscotched her way around the truth with a series of bureaucratic neologisms. Jovial, that is, unless you paused for a moment to recall that at least two people have committed suicide after receiving such “initial clarification letters”.

This exchange between Watt and Campbell is instructive.

WATT: I remember that earlier on in this inquiry we were told that, for those 20,000 letters a week that were being sent out, there was about a 20 per cent error rate. Is that figure still right?

CAMPBELL: We have never agreed that that is an error rate, and I think you and I have discussed this on many occasions. I think the Ombudsman too has discussed it. In fact, does someone have what the Ombudsman said about the error rate?

CHAIR (Rachel Siewert): Let’s not repeat what the Ombudsman said. We do know what the Ombudsman said.

WATT: So they are not debt notices; they are initial clarification letters. If they are not errors, what are they?

CAMPBELL: They are initial clarification letters where the recipient or former recipient has been able to provide clarification, which means that there is no need to continue with the process.

WATT: All right. When I say ‘error’, what do you say?

CAMPBELL: I say there has been an initial clarification letter, the recipient or the former recipient has been able to clarify the information, and there is no requirement for them to continue in the process.

WATT: Okay. Let’s call them ‘clarifications’, then. Is that an acceptable term? Do you want to take that on notice?

CAMPBELL: We will take that on notice.

It seems that Campbell does not acknowledge that Centrelink is making any errors at all (“we have never agreed that that is an error rate”). It was nimble footwork, and in the moment Campbell seemed assured and composed. But if you stop to think about what she admitted, the exchange with Watt was devastating.

As QUT academic Monique Mann told New Matilda, “there are always errors in data sets”.

“From a social science perspective, you account for errors in this, you have confidence intervals in decisions like this, I don’t think it’s acceptable to say, ‘there are no errors’.”

Campbell and her senior deputy Malisa Golightly were admitting that 20 per cent of Centrelink’s “initial clarification letters” were for fictitious debts. Debts that didn’t exist. Mistakes caused by Centrelink’s faulty data match.

Just don’t call them ‘errors’. They were, after all, just ‘clarifications.’

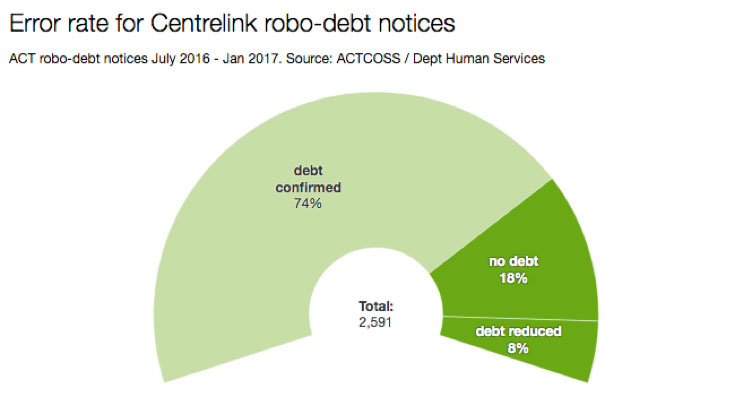

Think about that figure of 20 per cent. 20 per cent is one fifth. One in five of Centrelink’s data matches are wrong.

In fact, the true error rate is almost certainly higher. Data obtained from the Department of Human Services by Labor Senator Katy Gallagher shows the error rate for the robo-debt letters issued from the Australian Capital Territory between July 2016 and January 2017 was more than a quarter. The figures showed that of 2,591 debt recovery cases Centrelink opened from July to January in the ACT, 473 people were found owing no payment, while debt amounts were reduced for a further 195 – an error rate of 26 per cent.

As the government’s former Digital Transformation Officer Paul Shetler told the ABC in March, “if you’re looking at a 20 per cent failure rate, that company, if it was operating in a free market, would go out of business for very obvious reasons, and if it didn’t go out of business it would be shut down by regulators for fraud”.

Shetler told the ABC’s Colin Cosier that the Digital Transformation Office had been “locked out” of advising on the robo-debt process by the Department of Human Services, probably because the DTO might have insisted on some basic measures to improve the process.

“Generally speaking they were difficult to work with and very, very defensive,” Shetler continued. He likened the DHS response to “’nothing is wrong, everything is good, the house is burning down but everything is fine.’”

Nothing to see here, folks

Of course, everything is not fine, as the Senate Inquiry heard from numerous witnesses. Across the nine hearings of the Inquiry, held around the country, the litany of complaints reached a crescendo.

Time and again, the same issues were recounted.

Centrelink got its dates wrong, and ascribed income across a year to income that had occurred in a short period. Centrelink averaged income when it shouldn’t have. Centrelink mixed up the identity of employers. Centrelink had no record of documents sent to it. MyGov failed to upload documents properly. The Centrelink phone line was engaged. The Centrelink phone line was engaged. The Centrelink phone line was engaged.

“Andrej”, a recipient who spoke at the Brisbane hearings, was perhaps the most succinct:

The debt was false because, like for everyone else, Centrelink distributed my annual income across every fortnight of that year, including the nine months during which I was not employed.

One of the most devastating stories that emerged during the hearings was recounted in the session in Hobart by TasCOSS’s Kym Goodes.

One of the earlier calls that we got in our office, which I did not take personally but one of our team took, was from a woman who had been really overwhelmed by a call from a debt collection agency. It was the first time she knew that something was wrong — she had no prior knowledge of a letter or any attempt to contact her. She was overwhelmed by the fact that she had a debt. From memory, that debt was around $7,000 or $8,000.

So she agreed on the phone with that debt collection agency to pay back the debt, hung-up, was quite overwhelmed, and the next day spoke to a family member. When the family member started to unpack that with her, they realised that the debt was very unlikely to be valid. They helped her to make contact back with that agency and was told by them that, by entering into that debt repayment arrangement, she had actually confirmed the debt and, therefore, would have to continue to pay the debt back to them. She was also told by them that she needed to take up any other issues that she might have with Centrelink.

It is important to recount these stories. These are real Australians. The pain and anguish the government is causing these people is real. It puts the lie to the government line that Centrelink is ‘just seeking clarification’.

Late in the final hearing, Murray Watt asked Kathryn Campbell if she had met with the Australian Council of Social Service, or ACOSS, Australia’s peak welfare body. No, Campbell replied, she hadn’t. The reason she gave tells you all you need to know: because ACOSS had called on the Department to halt the robo-debt juggernaut.

I have not, to my knowledge, received a request other than the one in January when it was a very heated environment, I think it is fair to say. I gave evidence that the discussions were not going to be quite productive at that stage, because it was all about, ‘Stop, don’t do it,’ rather than, ‘How can we improve going forward?’

In other words, Campbell refused to meet with ACOSS because she didn’t like what they had to say. Even for a senior Canberra mandarin, the arrogance was breathtaking.

“I do not always have the time to meet with everyone on every measure,” she concluded.

Observers like Senator Skye Kakoschke-Moore were surprised, to say the least. Kakoschke-Moore, a senator from the Nick Xenophon Team, has proved one of the most diligent members of the Senate Inquiry. On every indication, the robo-debt program was in crisis. Meeting with key stakeholders is crisis management 101.

“It did [surprise me],” she told New Matilda. “Where efforts to meet are made, and approached in good faith, the way I understood ACOSS approached [the Department]with their repeated meeting requests was to address the mistakes made in the past but to look at a way to move forward.”

Kakoschke-Moore described Campbell’s testimony as nonchalant.

“[There was] a degree of nonchalance in how they addressed the questions and the community concern, particularly my questions about the voluntary code and way the protocols weren’t made public… they appeared to be surprised that people were concerned about the breach,” she said.

ACOSS chief executive Cassandra Goldie told New Matilda that “in some ways the most disturbing part of this is the behavior of the government, in light of the deep distress and the groundswell of terrible experiences from people affected”.

“This has had devastating impacts on individuals, and it has shocked me that senior members of government were not alarmed by this themselves, and did not immediately call in the representatives of people affected to get to the bottom of what was going on,” Goldie said. “Instead we’ve had senior ministers essentially saying that this system is working, and we’re just dealing with ‘teething problems’ or needing improvements.”

“The system that we’re talking about here – the social security system – is actually the lifeline for people when they are not able to look after themselves, whether it’s because they’re sick, or looking after young kids, or caring for someone else,” Goldie continued. “This is about will they have enough money to keep a roof over their head… that’s what at stake here, it should be at the heart of the government’s concern.”

The Ombudsman’s Report

Maybe Kathryn Campbell should have met with the welfare sector. If she had, she might have headed off some of the more damning findings handed down by the Commonwealth Ombudsman when he reviewed the fiasco in March.

The Ombudsman’s Report has been hailed by the government as exonerating the entire robo-debt process. On April 10, Human Services Minister Alan Tudge claimed that “the Ombudsman’s report shows that the online compliance system is reasonable in its data-matching and can accurately calculate debt owing”.

But that’s not what the Ombudsman said. In his media release on April 10, acting Ombudsman Richard Glenn was by no means complimentary.

“We found there were issues with the usability and transparency of the system,” Mr Glenn said.

There were deficiencies in DHS’ service delivery and communication to customers and staff when implementing the system. These issues affected the quality of decisions made by the OCI. Many of these problems could have been reduced through better project planning, system testing and risk management.

If you delve into the Ombudsman’s report, there are all sorts of stunning details. In the cases of ‘Ms B’ and ‘Ms G’, Centrelink sent emails to a woman giving birth and letters to the parents of a woman travelling overseas. When they weren’t responded to in time, Centrelink referred those debts to debt collectors. Both Ms B and Ms G’s debts were later drastically reduced, after they provided more information.

In the case of ‘Ms D’, Centrelink issued her with a debt of $2,200 even after she had filled in her data using the clunky MyGov site. As the Ombudsman wrote, “as she had accepted the ATO information while online, DHS averaged her gross income across the full period of her employment”. After she handed in paper copies of her payslips to a Centrelink office, her debt was reduced.

In the case of ‘Mr S’, Centrelink also averaged. He had entered in his annual data and thought it to be the correct figure – indeed, it was the correct figure. “DHS told us it had averaged his income over the period of employment, as Mr S confirmed his information online on 22 October 2016.”

Averaging is critical, because it has been the direct cause of most of the false positives that the robo-debt compliance system has thrown up. This is the problem where a Centrelink recipient might have worked for a few months in a previous year and then claimed unemployment benefits. If there isn’t enough information in the ATO data match to place definite dates on income earned in a given financial year, the Centrelink data match will simply average this amount across 26 fortnights. Tens of thousands of innocent Centrelink recipients appear to have been caught out in this way.

In the case of ‘Ms H’, the Department made multiple errors. She had stopped working for a business in November 2010, and had told Centrelink at the time. Then she claimed Newstart. Centrelink decided – wrongly – that she had worked for the whole financial year, and issued her with a debt. The DHS also refused to accept her bank statements as evidence of not working for that employer, and told her to complain to the Australian Tax Office instead.

“DHS acknowledged a number of errors had been made in Ms H’s case,” the Ombudsman wrote. Her debt was reduced to zero.

Then there was the case of Mr J, who spent more than five hours across four separate phone calls and one visit to a physical Centrelink office to question a $92 debt. Centrelink later waived it. The DHS stated in a compensation decision that “Mr J was unable to receive consistent information regarding the debt or how it was calculated.”

But perhaps the most damning finding of the Ombudsman’s Report is that the Department of Human Services never bothered to check whether its ongoing use of income averaging would cause problems.

As the Ombudsman’s report states, on page 42:

We asked DHS whether it had done modelling on how many debts were likely to be over-calculated as opposed to under-calculated. DHS advised no such modelling was done.

In other words, the Department never bothered to consider how many mistakes it would make. It just spooled out the drag net, confident in its assertion that the fact that it was merely seeking clarification would absolve it of all responsibility.

As La Trobe University’s Darren O’Donovan told us, “the data match was inevitably primed to over-calculate the debt”.

One of Australia’s foremost experts on the interaction of welfare and administrative law, O’Donovan has been taking a special interest in the robo-debt inquiry. “I think it is fair comment to say that the publication of the Protocol establishes that matching with ATO data was always going to be imprecise, under-inclusive of key information, and not adapted to the modern realities of casualisation and seasonal work,” he wrote in an email.

“The robot’s function is to in-build income averaging, traditionally a last resort for a decision-maker who had interacted with the individual, to hundreds of thousands of debt estimates.”

O’Donovan points out that the averaging errors were then combined with a reversal of the onus of proof, making welfare recipients responsible for any missing information. “The combination of the two was not viewed as risky by the Department and they never did any modelling, according to 2.33 of the Ombudsman report.” O’Donovan wrote.

“Most worryingly of all, in the future, algorithms may not actually be explainable,” O’Donovan warned. “The reality is that technology is outstripping our ability to narrate it.”

A “privacy omnishambles”

QUT privacy expert Monique Mann compares the robo-debt fiasco to the movie I, Daniel Blake. “It’s a Kafka-esque nightmare,” she told New Matilda in an interview. “There are real questions about the reliability of the data and the program used to match data between Centrelink and the Australian Taxation Office.”

“There are also serious concerns with removal of human oversight of computer-based systems and automated decision-making leading to errors, further compounded by limited avenues for review and appeal.”

Mann, an academic who is also a board member of the non-profit Privacy Foundation, worries about the transparency of such algorithms. “Academics call this ‘black box decision making’: we don’t know how the algorithm works, we don’t how these decisions are being made, this is all very opaque and it is very problematic.”

Mann calls it a “privacy omnishambles,” mentioning the disastrous 2016 Census and the passage of the notorious metadata retention laws in 2015. She also points out that the government’s Digital Transformation Agency is currently working to develop what it calls a ‘trusted digital identity framework’, which it touts as making “the process of proving who you are to government while online simple, safe and secure.”

Mann says the DTA is proposing that facial biometrics technologies are being considered for use in the trusted digital identitifer. “Privacy advocates are incredibly concerned about this.”

At almost every point in the robo-debt scandal, privacy has been a central issue. In March, it emerged that the Minister’s office had disclosed the private information of blogger Andie Fox to a journalist from Fairfax, after Fox wrote an article detailing her experience dealing with a Centrelink robo-debt. Minister Alan Tudge and the Department claimed that it was necessary to do this, to protect the “integrity of the system.”

As I reported in March, the implications of the action are stark: the government had “doxed” a critic. The Department, in collaboration with the Minister’s office, had pulled the file of a blogger who had criticised the robo-debt program, and then backgrounded a friendly journalist with her private information. Tudge claimed he had a legal brief that advised that the disclosure was legal. But he has refused to release the advice. The intentional disclosure led to a police investigation of Minister Tudge, but he was cleared.

In response, Information Commissioner Timothy Pilgrim is ramping up the penalties for government agencies that breach privacy guidelines. There will be a mandatory privacy code for federal departments and agencies, rather than the voluntary regime that exists now.

In her interview with New Matilda, Senator Kakoschke-Moore argued that the new privacy code is “an admission that the voluntary codes are too weak”.

“The fact that the voluntary code leaves too much wriggle room not to comply with, and that the government was shown not to have complied with it in this project raises alarm bells and raises concerns, not only for me but for members of the community that the government is lacking in transparency,” Kakoschke-Moore said. “What have they got to hide?”

Privacy advocates claim the new code will make no difference. Well-known privacy expert Roger Clarke said recently it was “nothing but a smokescreen for failures by government agencies to comply with their longstanding obligations”.

It remains to be seen whether the Information Commissioner continues his investigation into Centrelink, or whether the new code will strengthen the government’s disastrously weak protections. So far, the Department has faced no sanction for its intentional disclosure of Andie Fox’s file.

The damage done

Whatever the blithe assertions of Tudge and Campbell, for many disadvantaged communities, the impact of the robo-debt roll out has been extreme.

Because of the nature of Australia’s tightly-targeted welfare system, a program like this will, by definition, hit the poorest and most vulnerable hardest.

Take Tasmania. The island state has long had some of the nation’s worst figures for poverty, inequality and literacy. Around a third of Tasmanian households rely on Centrelink for some or all of their fortnightly income. The state’s internet connectivity is the worst in the country. A punitive online compliance system requiring high levels of functional literacy and plenty of internet access was almost designed to fail.

When the Tasmanian Council of Social Services’ Kym Goodes got to speak to the Senate Inquiry, she didn’t mince words.

“What the Australian government has done to Tasmanians in the last six months is almost incomprehensible,” she told the Senators.

It has been an erosion of trust, an erosion of human rights, an erosion of dignity and an erosion of the principles of good government decision-making. Unconscionable conduct is generally understood to mean conduct which is so harsh that it goes beyond good conscience. It is conduct that is particularly harsh or oppressive, conduct that is even more than unfair, and it must be against conscience as judged against the norms of our society. It was always highly likely that this system would be particularly harsh in Tasmania.

Goodes made the crucial observation: many welfare recipients simply don’t have the intellectual and emotional resources to deal with the heavy hand of Centrelink’s bureaucracy.

The chair of the Senate Inquiry is Western Australian Greens Senator Rachel Siewert. She was scathing of the Department of Human Services and Minister Alan Tudge’s bungling.

“They didn’t acknowledge that the portal wasn’t up to it, that it was dysfunctional, that people couldn’t get on,” she told New Matilda in a phone interview. “The letters themselves are unintelligible… they just said ‘We want to get these people, send out the letters, press the button’. [The] phone lines weren’t working properly, it was just gung ho, go for it, and now.”

“There is no doubt that there is a power imbalance between the Commonwealth agency, which is the Department of Human Services, and an individual citizen. Many of the people that I have spoken to were overwhelmed by the enormity of what they were being required to prove, and they were crushed by that power imbalance.”

Siewert told New Matilda that it took 41 pages of web page print outs to describe a single interaction with the Online Compliance tool on MyGov.

“What Centrelink gave us is basically a handout which has 41 screens on it, I’ve literally got it here in my hand,” she said. “So you could have to go through 41 screens [to provide Centrelink with the correct income information], and some people have low literacy and numeracy skills.”

Kokoschke-Moore agrees. Centrelink’s byzantine bureaucracy is so bad, she said, that welfare recipients asked to provide extra information often have to lodge a freedom of information request for their own documents.

“We’ve heard that when people FOI, they are confronted with hundreds of pages of tables and acronyms that make no sense whatsoever; we asked the Secretary to look at the documents handed to us by a lawyer, [the Department]said it wouldn’t be a good use of their time, so what hope does that leave for you and me and ordinary citizens to understand those documents?”

Siewert points to the reversed onus of proof applied to welfare recipients caught in the coils of the Centrelink robot.

“The government continues to say the onus of proof is on the person to prove that the data is correct,” she said, “but essentially the government system is flawed, because it misidentifies a debt because the employer has not sent the periods of employment.”

“[That is] no fault of the person getting the letter. Because the data is not lining up, they get this letter. The government can do all the semantics they like to say the onus is not on the person… it is.”

After listening to weeks of harrowing testimony, Siewert has found the Senate Inquiry a draining experience.

“You come out of those hearings and you feel really drained. The evidence we hear is very distressing – hearing of people’s experiences and feeling their sense of powerlessness and despair.”

Function creep: robo-debt and Data61

And yet, despite everything we’ve learned about the robo-debt disaster, the government is pushing ahead. In fact, the automated data-matching is expanding. The data trawl will expand to disability and aged pension recipients next.

New Matilda has already heard about one report – so far unconfirmed – of a $90,000 debt being issued against a disability pensioner. In the new financial year, the government will begin drug testing an estimated 5,000 welfare recipients.

One of the most fascinating aspects of robo-debt is the way it appears to be metastasizing across the federal government, pulling in agencies that no-one would have expected to be involved in the control and supervision of citizens.

Take Data61, the data science arm of the CSIRO. Data61 presents itself as “Australia’s leading digital research powerhouse”. But now we know the agency is also working for the Department of Human Services to help fix the robo-debt mess. The CSIRO is also going to be working on the drug testing of welfare recipients, as Senate Estimates testimony last month revealed.

To say that CSIRO and Data61 scientists are unhappy about this is an understatement. New Matilda has spoken to sources inside the agency that are deeply troubled by the development.

Industry news site InnovationAus has also picked up the disquiet. Journalist Denham Sadler reported in June that “the proposed Data61 involvement in identifying welfare recipients for drug testing has caused some anxiety among staff, with some experiencing an ‘existential crisis’ over the issue.”

The role of the CSIRO has traditionally been public-interest scientific research. Many inside CSIRO and Data61 question whether drug testing welfare recipients and tweaking the robo-debt algorithm is truly in the public interest.

Blaming the non-victim

And still the robo-debt tentacles spread. At every stage of the slow moving robo-debt disaster, both the government and the senior bureaucrats at the Department have covered up and denied. Time and again, in the face of graphic evidence, they have insisted that nothing is wrong.

The debt letters weren’t really debt letters, they claimed – even when they were handed over to debt collectors. The online compliance system wasn’t really a big change, they argued – despite ramping up a system that issued tens of thousands of new notices every month and that was budgeted to raise hundreds of millions of dollars from welfare recipients. There weren’t actually any errors, they said – and then admitted that the error rate was actually 20 per cent. The Ombudsman cleared the Minister and the Department, Alan Tudge claimed – when a close reading of his report showed anything but. Tudge keeps claiming “the system works”, even as appeals to the Administrative Appeals Tribunal have risen by 50 per cent.

Underlying the bluff denials is a belief amongst top department officials and the Minister himself that the welfare recipient is always to blame (even if they’ve done nothing wrong). As we heard repeatedly in the Senate Inquiry, if the Department is merely asking for more information, then the bureaucracy can’t be at fault.

The delusion is palpable. Tudge, Campbell and the top brass are completely divorced from the reality on the ground (or on the phones). Wracked by industrial action, intentionally expanding a broken data match program, and unable to answer the phone, Centrelink is an agency in crisis. But Tudge and Campbell can’t, or won’t, see it.

There are many unanswered questions. Many of the questions put to the Department by the Senate Inquiry and taken on notice still haven’t been responded to.

Why did Centrelink suddenly update the Program Protocol in April 2017, only after the commencement of a Senate Inquiry and a letter from the Information Commissioner? Why was Victoria Legal Aid stonewalled in the foyer of a Canberra office building? Why was an FOI for the Protocol denied, and then granted after the documents surfaced at the Senate Inquiry? Why was the Program Protocol changed to omit a reference to a “customer’s record”? And why was Andie Fox’s data released?

As the Inquiry’s chair Rachel Siewert asked at one point in our interview: “the risk assessment stuff – why wouldn’t you do that?”

Labor’s spokeswoman for Human Services, Linda Burney, calls it simply “a failure of public policy,” arguing that there was “no proper planning, no risk assessment or no consideration of its impacts at all.”

“What is very clear is that there is a cultural problem at Centrelink, one that starts with the Minister and the Executive staff,” Burney wrote in an email. “It is a culture which only blames clients when things go wrong. Most of the staff I speak with want to help, but they don’t feel that they are allowed to.”

“There is no question that robo-debt was a failure of public policy, and ultimately that failure lies at the feet of Alan Tudge.”

“Let’s be clear what the Department was doing,” Victorian Legal Aid’s Dan Nicholson’s told New Matilda at the end of our interview.

“They had a significant rate in increase in the debt, they removed human oversight and they were using data matching assumptions that were fundamentally flawed.”

“There are very real human consequences to a very large number of people, who are having debts alleged against them, which are probably wrong.”

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.