They finally had a win… although that depends entirely on your definition. Ben Eltham explains.

For an ordinary second-term government, passing half of a company tax bill first announced a year ago would not normally offer cause for celebration.

But these are not normal times, and the Turnbull government is not particularly ordinary in its languishing performance.

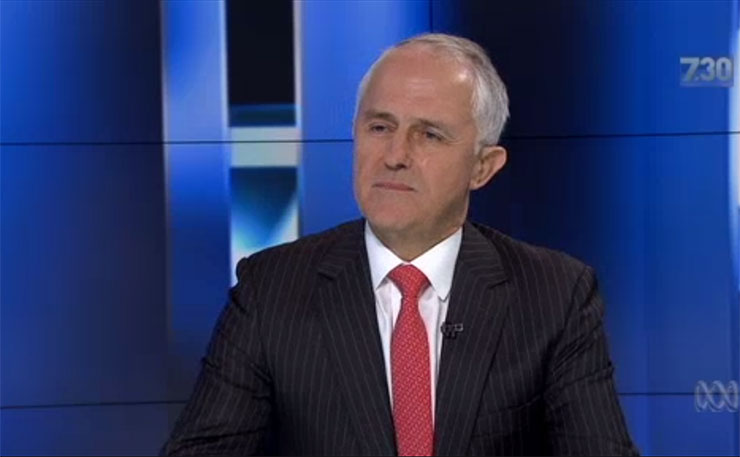

Mired in a slough of unpopularity, and riven by internal tensions, the Coalition has struggled since its re-election with the normal processes of government. At this stage of the Rudd-Gillard years, Julia Gillard was forging ahead with an ambitious second-term agenda that included a comprehensive carbon tax and the National Disability Insurance Scheme. Malcolm Turnbull has mainly occupied himself with replacing sacked ministers and placating the Liberal hardliners with bottom-shelf measures like amendments to the Racial Discrimination Act.

So the deal with the Senate cross-bench last Friday to implement a company tax cut is a big deal for the Turnbull government.

The agreement, secured in negotiations with Nick Xenophon, delivers a 5 per cent cut in the company tax rate for firms with turnovers below $50 million a year. Those firms will pay 25 per cent instead of 30 per cent on their profits, with the tax cut phased in over a 10-year timetable. The government claims 3.2 million businesses will benefit.

In return for his vote, Xenophon extracted a series of sweeteners for his constituents in South Australia, including a one-off welfare payment to pensioners worth around $260 million. Recipients of the age and disability pensions and the parenting will get $75, or $125 if they are couples. There is also a $110 million loan for a solar thermal plant in Port Augusta, which could see a thermal plant built in Australia for the first time.

The government also agreed to yet another review of energy policy; those watching the Coalition’s faltering efforts on energy in recent years will not be holding their breath for sweeping reform.

The government is of course hailing the agreement as a win for “jobs and growth”. In truth, it is mainly a win for shareholders of companies. The Treasury modelling of the full $50 billion package promised at the 2016 election held out the prospect of only very modest benefits for economic growth — around 1 per cent over 10 years. Not even the most fervent believer in laissez faire economics could get too excited about that. No-one has done any work at all on what sort of benefit the smaller tax cut for smaller companies will achieve. Most likely, any effect on employment will be negligible.

In contrast, the hit to the budget from the tax cuts is very real. The tax cuts mean roughly $24 billion in revenue will be subtracted from the budget in coming years. That’s money that will no longer be available to pay for roads, schools and hospitals. The budget is already in deficit to the tune of roughly $36.5 billion this year.

So this is bad news for the budget. But it is a win for the government in political terms. The company tax cut was an election promise — indeed, company tax cuts were just about the only 2016 Coalition election policy worth noting. So it’s understandable that the government is pleased.

Turnbull and his colleagues have had precious few legislative victories in recent times. The deal with Xenophon delivers something that Turnbull has been desperate for: a win for his Liberal base in the corporate sector.

Not particularly surprisingly, business types have been clamouring for the tax cut. While Friday’s deal won’t give big business what they asked for, it certainly gives some assistance to smaller and medium-sized companies: precisely the sort of businesses that tend to support the Liberal Party.

And that’s probably the best way to understand this deal: as a government delivering for its political base. With little overall benefit to the broader economy, and in the context of a government implementing harsh austerity on welfare recipients, this is effectively an upwards redistribution: from low and middle income earners to business owners.

Whether the company tax cut is good politics in the longer term is yet to be seen. It cannot have escaped many voters that at the same time the government is delivering company tax cuts, it is also presiding over reductions in penalty rates for low-income workers in the hospitality and retail sectors.

By giving companies a tax cut and handing hundreds of thousands of workers a pay cut, the government has made its policy intentions crystal clear. It has also handed Labor a potent weapon in the lead-up to the next election.

Labor is refusing to rule out reinstating company taxes should it win office, and nor should it. The opposition can now promise not only to restore penalty rates but to raise company taxes in the name of budget repair. Both policies will be popular. They might even be good for the economy too.

In recent years, we’ve seen the fever-dream of neoliberal politics fade, as first economists and then ordinary punters woke up to the accelerating inequality in western democracies. In Australia, this has resulted in a much sharper class rhetoric from the voices both capital and labour. Business groups and the Liberal Party have mounted near-hysterical attacks on the supposed power of trade unions, while unions and the Labor Party have honed their critique of a business elite utterly out of touch with ordinary citizens.

Last week, for instance, we saw new ACTU boss Sally McManus openly decry neoliberalism and inequality, while calling out corporate wrong-doing and greed. This kind of rhetoric would have been inconceivable even a decade ago, much less under grey-faced apparatchiks of the 1990s like Martin Ferguson. The response of the business media and The Australian was hyperbolic. Class warfare is back with a vengeance.

In doing the bidding of business, the Coalition is doing no more than fulfil its historic role as the representative of business interests in the federal Parliament. But that doesn’t make pro-business policies popular. The reverse is more likely to be the case.

It doesn’t like being told so, but Australia’s business class is woefully out of touch. If you meet some of these elites, this is immediately apparent. Largely old, white and male, big business doesn’t look like ordinary Australia because it’s not ordinary Australia. The general population is younger, browner, poorer and more female than business elites.

Top executives in the 1 per cent simply don’t understand what it’s like to have nothing in their savings account for a week before pay day. They don’t know what it’s like to pay more than half their meagre income just to keep a roof over their head. They don’t get that many lower-income Australians are hurting. This is why business leaders can confidently argue that a tax cut for them is good economics, even when most economists argue that it isn’t.

Voters aren’t stupid: they understand that a Liberal government will tend to oppose unions and favour its donor base in business. But that doesn’t mean they have to like the policies that result.

An Australian trade union movement and an Australian Labor Party finally prepared to again fulfil their roles of championing the rights and interests of ordinary workers will be well placed to reap the whirlwind of big business’ hubris.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.