The Coalition’s corporate tax cuts are about propping up an unsustainable economic model, writes Ian McAuley.

The Turnbull Government has re-affirmed its determination to pursue corporate tax cuts, justifying its proposal in terms of international competitiveness and its “jobs and growth” mantra.

These are fallacious and weak arguments, but the government’s real agenda is more probably about enticing foreigners to keep on buying our assets (aka “foreign investment”) so as to postpone the day when we have to face up to the hard reality of living within our sustainable means.

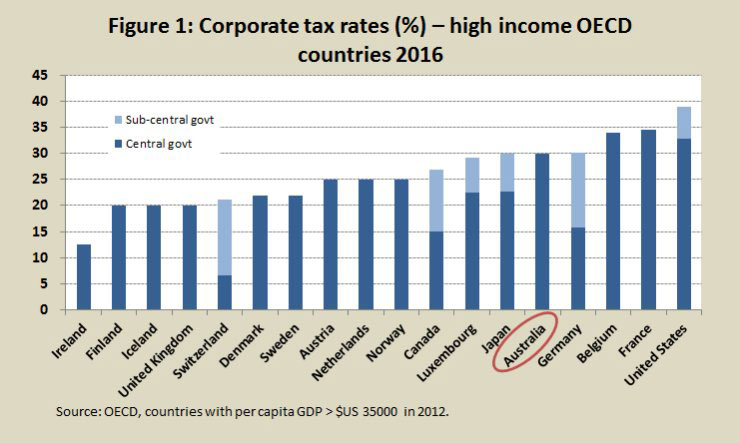

Australia’s general rate of company tax is 30 per cent (with a concessional 27.5 per cent rate for small businesses with annual turnover under $2 million). At first sight this suggests, in comparison with other high-income OECD countries, that our corporate taxes are on the high side. See Figure 1 below.

From this perspective the Coalition’s proposal to cut company taxes, initially to 27.5 per cent for all businesses and eventually to 25.0 per cent, looks reasonable. It would bring us pretty well into line with the average 25.7 per cent in other high-income countries, particularly in light of Trump’s hope to cut US corporate taxes to 20 per cent and possible tax cuts in France after its election.

That is, until one realises that Australia is unique among high-income countries in having a full dividend imputation system, a reform introduced by the Keating Government in 1987 (Canada and the UK have partial dividend imputation).

Under dividend imputation, when an investor (an individual or a financial intermediary) receives a dividend there is a credit for the company tax already paid on the profits that financed that dividend. If a company is paying out around half its profits as dividends (which is a typical long-term payout rate in Australia), the effective company tax rate for the investor is only 15 per cent (30% x (1.0 – 0.5)), which us puts down among the low-tax end of the scale (for a more complete explanation of dividend imputation, see a recent contribution by Ross Gittins).

If the Coalition’s tax cuts go through, most Australian investors would see no benefit. What they would gain in lower corporate tax rates would be exactly offset by lower imputation credits.

Perhaps the government expects that a lower corporate rate may encourage companies to retain a higher proportion of earnings (over last year, in the absence of opportunities for expansion, companies have been paying out 70 percent of profits as dividends).

But economists generally believe that companies should be encouraged to pay out dividends so that investors rather than company boards make capital allocation decisions. Think how much better off shareholders would be if BHP hadn’t taken over Billiton, or if Rio Tinto hadn’t taken over Alcan and instead had paid out higher dividends so that shareholders could have chosen where to invest.

Boards and senior managers seek corporate growth as a path to high executive salaries and status, while investors seek sound investment returns. But investors – the millions of Australians with superannuation accounts and share portfolios – don’t have the easy access to government enjoyed by the corporate elites. Hence the business lobbies’ strong support for the Coalition’s cuts.

An even stronger explanation for the Coalition’s enthusiasm for corporate tax cuts is that imputation is confined to domestic investors. Therefore a cut in corporate taxes would benefit foreign investors.

For almost all of our post-1788 history, Australia’s economy has operated on what may be called a “settler-economy” model, reliant on foreign sources to provide investment capital. A surplus on foreign investment is balanced by a deficit on current account – the difference between our imports and exports. That’s an accounting certainty: if we’re spending more than we’re earning we must be running down our savings or going further into debt.

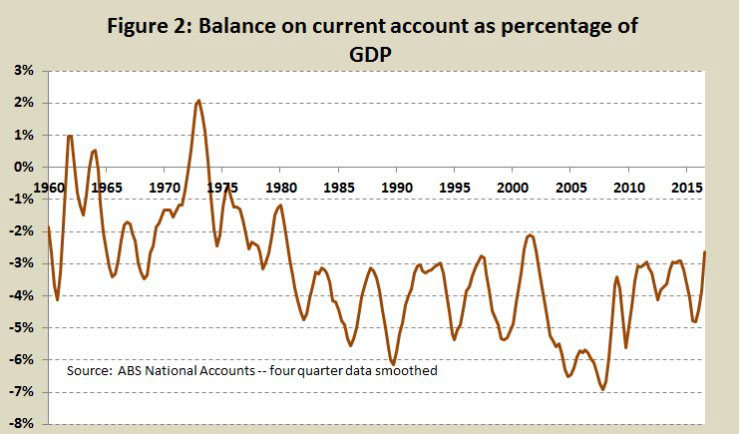

That model makes sense in a growing “underdeveloped” country, but in Australia it should be well past its use-by date. Apart from some occasional short-lived surpluses (the last was in 1973), we have been running a consistent deficit on current account, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Thanks to temporarily high commodity prices there has been a recent improvement in our position, but most economists expect this boost to be short-lived.

Over time, deficits in a country’s current account accumulate into foreign liabilities – another accounting certainty – and our net foreign debt, at 1.02 trillion dollars, is now labelled by Standard and Poors as “extreme”.

This is the debt Treasurer Morrison hardly ever mentions. He’d rather talk about the modest government debt accumulated by the Rudd-Gillard Government (even though successive Coalition governments have let government debt expand much further).

It’s the debt that finances our trip to Bali or to the Winter Olympics, our Toyota Corolla or BMW 340, our t-shirt made in Bangladesh or our Louis Vuitton handbag made in France.

Some day the rest of the world will remind us the hard way that it’s not prepared to go on lending to us to support our standard of living. The Coalition’s corporate tax cuts are what may be a last-ditch effort to defer that day, at least until after the next federal election.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.