For our current Prime Minister it was never really about ‘the public service’, rather the service the public can provide him. Fergus Peace explains.

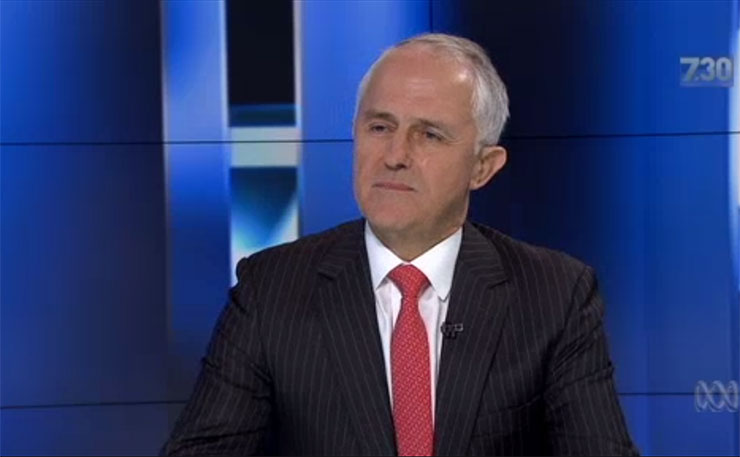

John Clarke and Bryan Dawe are the doyens of Australian political comedy, and for their first outing of 2017 they had Malcolm Turnbull in their sights.

“What’s the future for the renewables industry, do you think?” asks Dawe, the straight man of the duo. Clarke’s Turnbull blinks. “Privately, Bryan, or publicly? In Australia, or when I’m overseas at a climate change forum? In Western Australia, or Sydney?”

It’s a good joke, but not by now a very original one, a comic variation on what might be the main theme of our political debate: the Prime Minister as a man who’s put his ideals on the shelf under intense pressure from conservative rebels, who feels boxed in and unable to pursue what he really believes in.

For all its ubiquity, though, this story gives Turnbull too much credit. In the 18 months since he became Prime Minister, and nine since he won re-election, there’s been no sign he really believes in anything at all.

Turnbull became the darling of social liberals on both sides of the aisle roughly at the moment he lost the leadership of the Liberal Party. For five years, when self-anointed reasonable people looked out on the political landscape, they saw a Labor Party beset by squabble and scandal (and sexism) and Tony Abbott on a single-minded quest to bastardise public debate for no discernible purpose.

Contrast Malcolm Turnbull, this eloquent silver fox who gave speeches arguing for marriage equality, called Australian refugee policy cruel, and went down fighting for the cause of climate change. It didn’t hurt, of course, that he’d been brought down by Abbott, who (depending on your party affiliation) was either public embarrassment or public enemy number one.

The sigh of lament and longing for Turnbull was everywhere. Eventually, inevitably, the embarrassment became too great and Abbott was turfed. And then? No marriage equality, and a commitment to the same plebiscite Turnbull had earlier lambasted; no reversal on climate change; continued intransigence and denialism about the refugee camps in Nauru and PNG.

Of course this is not by choice, and this is the story we keep telling ourselves. Privately, he wants to do these things, but the Cory Bernardis and George Christensens of the world stop him. With a wafer-thin majority and an unruly Senate, Turnbull is constrained by his rebellious colleagues and unable to act on his principles.

But this excuse can only run so far. Take marriage equality. A majority in both houses of Parliament support change, along with a majority of the population. All Turnbull would have to do is announce that he’s allowing a free vote on one of the several bills that have been proposed, and equal marriage would be a reality (for good measure, most people think this is exactly what he should do). So why not do it?

The conservative wing of the Liberal Party would not be happy, but sometimes prime ministers have to face down internal opposition. If Turnbull elects not to make this one of those times – to continue being ‘constrained’ by opposition from people who repeatedly swear they’re against mid-term changes of leadership, on an issue where the public is clearly on his side, at a time when he’s significantly more popular than his party – there’s no good reason for us to think that he ‘really believes’ in marriage equality at all.

Climate change is a bit more tricky. Tony Abbott very successfully tapped into and then promoted the tendency in the Liberal Party towards climate denialism in both outright and thinly-veiled varieties. It really would be prohibitively difficult for the PM to lead environmental policy in a better direction.

On the other hand, it would be very easy to refrain from marching around the country singing the praises of (‘clean’) coal, or from launching baseless attacks on renewable energy for the sake of scoring points against a Labor government in South Australia.

Perhaps if it was just up to him, Turnbull would be implementing an ambitious emissions trading scheme. But he shouldn’t get credit for that when, here in the real world, he’s not only failing to reduce reliance on fossil fuels but actually attacking those who try to do so.

That’s not the behaviour of someone who is really committed to fighting climate change but is regrettably limited by his MPs. It’s the behaviour of someone who is really committed to keeping himself in power.

That’s the other question we need to ask: why? It would make some sense if Turnbull was sadly compromising on his beliefs in order to keep his government together, in pursuit of some other important goal. But he doesn’t appear to be trying to do anything in particular.

At the time of his leadership challenge, Turnbull criticised Tony Abbott for a lack of economic leadership and promised to bring more serious policies and promote them in a more serious, less sloganised debate.

When he called the double dissolution election, he called for a contest about the bold reforms Australia needed to face its economic challenges. He ended up proposing a company tax cut, and spent the campaign maintaining the desperately implausible line that this was a game-changing policy that Labor would doom the country by rejecting.

The rest of the campaign consisted of an invented budget black hole and periodic inflammatory comments about refugees – that is to say, the same formula the Coalition has used at every election in recent memory. Whenever Turnbull says he wants something lofty, it’s only a matter of time until it vanishes into a cloud of political expedience. It’s hard to spot any guiding light.

The fact is that Malcolm Turnbull knew he wanted to be Prime Minister before he knew why. He entered public life through the campaign for a republic, probably the most vanilla and ideologically neutral cause to be found in Australian life. He entered Parliament in 2004 after a few years’ wondering about which party he should run for.

At one point, he wanted to lead the Australian Workers’ Union, an ambition so staggeringly incongruous with the actual course of his life that it’s hard to view it as anything other than a generic lusting after public prominence and power, a preliminary version of his designs on the prime ministership.

The role is what he wants, more than to do anything in particular with it. It showed in the way he coquettishly basked in the admiration of liberals during the Gillard/Abbott years, giving those speeches not just to win followers but to reinforce his own view of himself as the most thoughtful and well-spoken politician in town.

It still shows: the moments Turnbull really lights up, these days, are the set pieces where he gets to play at being Prime Minister, like a kid at Youth Parliament enjoying the thrill of speaking without needing to find anything meaningful to say.

His attack on Bill Shorten in Parliament last month is a case in point: asked about cuts to family welfare payments, Turnbull launched into a tirade about Shorten’s sycophancy and ‘social climbing’, revelling in his own putdowns and visibly enjoying the applause of his colleagues.

And they were good putdowns, but what was the point? It’s time to stop pretending that, for Malcolm Turnbull, there is one. Eighteen months of political abjection have made it perfectly clear that Turnbull is not animated by any deep passions or values.

He’s the Prime Minister, and that’s the point: he gets to give the speeches, travel to the summits, sound dignified and important. He’s good at it – he’s still the same confident, eloquent man we all fell for.

But all the things he said he cared about have fallen away, and revealed that inside, there’s nothing there at all.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.