Binoy Kampmark looks back on the life of a man who refused to come to heel.

Reactions were generally predictable to the passing of Fidel Castro. Britain’s Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn, spoke of Castro as that “huge figure of modern history, national independence and 20th century socialism”. The stage was set by his record in establishing formidable health and education systems, while forging a “record of international solidarity abroad”.

The socialist vanguard could only but trumpet the historical legacy of a man indivisible with the legacy of the post-colonial world. By way of contrast that great foe, the United States, incapable in subjugating a state it regarded as monstrous and satanic in regional and global influence, provided a register of delighted accounts. What the US intelligence services or assassins could not do, nature did.

South Florida was typically heady with celebration. Miami’s Little Havana and Southwest Miami-Dade became noisy with banging pots, pans and car horns. Sergio’s, a local franchise of Cuban restaurants, watered patrons with complimentary Cuba Libre cocktails.

Various publications stuck to the ideological lines. Jim Geraghty did not trouble himself too much with historical analysis, thrilled that Castro was dead, “which is good news. I suspect he’s finding the afterlife surprisingly scorching right now” (National Review, Nov 26).

For Geraghty, communism was the traditional bug bear that needed to be slain, and he was very happy to report that Castro lived to see the collapse of ideas and states: the fall of the Soviet Union, the abandonment by China of “communist economics if not statist brutality” and the “collapse of Venezuela.”

As for Vietnam, it was duly capitulating to US economic imperialism, with its cities awash with “American icons like McDonalds, Subway, Starbucks, and Kentucky Fried Chicken”. In this primitive assessment, Colonel Sanders will always “conquer the free market”.

Simplicity is ever the default position of the ideologue. Castro’s regime, argued George Will, was “saturated with sadism” and “should never have existed.” Will lists Castro alongside other “progressive despostisms” with their admirers, taking issue with Jean-Paul Sartre’s swooning with the country’s Máximo Lider on visiting him, the revolution still fresh.

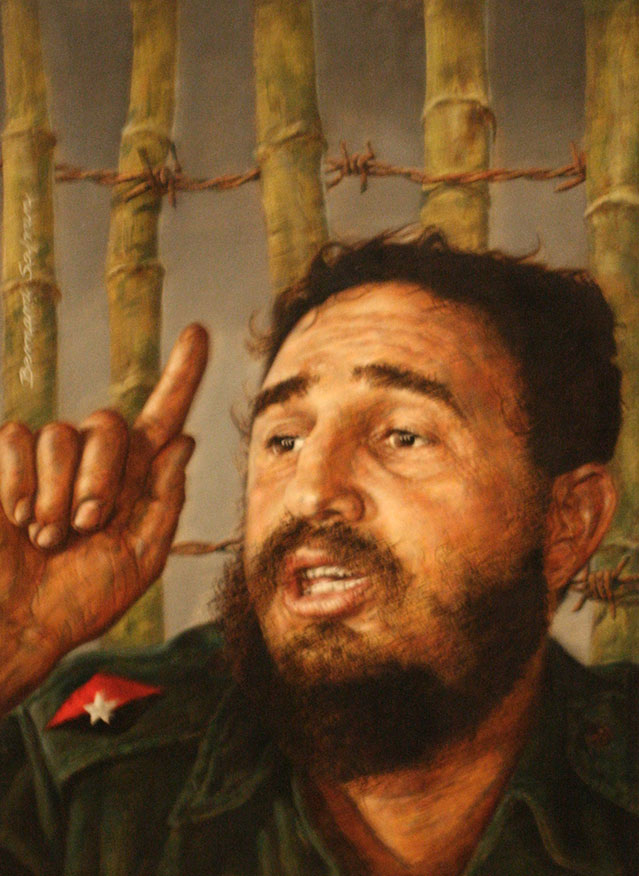

Such hatchet vitriol, indifferent to broader achievements, explains the sheer effect of the man. Castro simply refused to go away, much like his incessant multi-hour oratorical efforts on the podium. In 1959, he cleansed the stables long soiled by US barbarity and the regime of Fulgencio Batista, up-ending generational attitudes on race and economics.

This point is contested by Castro detractors, as it always will be. To the myopic US eye, one supplied by a PBS summary of pre-Castro Cuba, the country was not the “brothel of the Western hemisphere” where the hungry poor facilitated exotic living for the wealthy. “Rather, Cuba was one of the most advanced and successful countries in Latin America.” Such stunted assessments beg the question: revolutions only tend to take place in the absence of success and wealth.

The most monumental battles were always against what might seem to some as dated struggles, frozen in the tableau of Cold War tensions. But, as Piero Gleijeses reminds us, Castro’s energy was not purely marshalled against the United States and its military meddling in the Western Hemisphere. The project was far broader, encompassing “a fight against poverty and oppression in the Third World” (London Review of Books, Aug 19, 2004).

Havana became beacon, sponsor, and mischief maker in chief for revolutionary causes. It entailed assistance to Algerian rebels fighting their French masters in 1961. It saw conflict in Zaire, where Cubans led by Che Guevara engaged a thousand CIA-backed mercenaries.

Most famously, and definitively, it was Castro’s insistence in deploying 30,000 Cuban soldiers to Angola in 1975-6 that frustrated South African ambitions (and therefore those of Washington), etching him into the anti-imperialist canons of history. The apartheid regime never quite recovered from the blows levelled by Cuban forces.

The result of Castro’s broader project was more than a military one. It saw the creation of a vast Cuban humanitarian effort, with medical teams operating in places of crisis across the globe with minimum cost. In turn, the Escuela Latinoamericana de Medicina became a Mecca for Latin American and African students who would not, in many instances, have had a stab at decent medical education.

Castro, over time, became the worn idea of an audacious effort, one that decayed, partly by its own hand (persecuting dissidents, police state methods, despotism) while still seeming solid in the face of superpower paranoia. According to Régis Debray, the Castro portable library eventually diminished to history pure and simple, a sense of self in history. He became “obsessed… by historians in the future and his own posthumous image”.

Castro proved to be a survivor, durable even as the US changed before his eyes, but such systems as those in Cuba run with the man, an amalgam of strength and flaws. Investors from across the pond are smacking their lips, looking forward to seeing the state-directed economy wither before the onslaught of hard US currency.

The normalisation of Cuban-US relations will, in large part, spell an end to Castro’s Cuba, with the old hands passing into the books, along with utopia. But the historical record, in its complexity and sheer scale, stands in all disproportion to the man and his country.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.