How the labour movement and women denied the government and its Generals conscripts during World War I. By Hall Greenland.

This week marks the centenary of arguably the most democratic event in Australia’s history. But it is one the establishment would rather forget.

At the height of the First World War, on October 28, 1916, Australians went to the polls to decide whether men would be conscripted for the trenches of the Western Front.

Neither the War Museum nor the Museum of Australian Democracy believe this event that aroused the country (the voter turnout was a record) is worthy of special notice.

Possibly the establishment’s reluctance stems from the people’s rejection of conscription, although the ‘No’ majority was a slim 72,476. Possibly also because – incredibly – the main argument for conscription made by the government and the generals was that Australia was not doing enough.

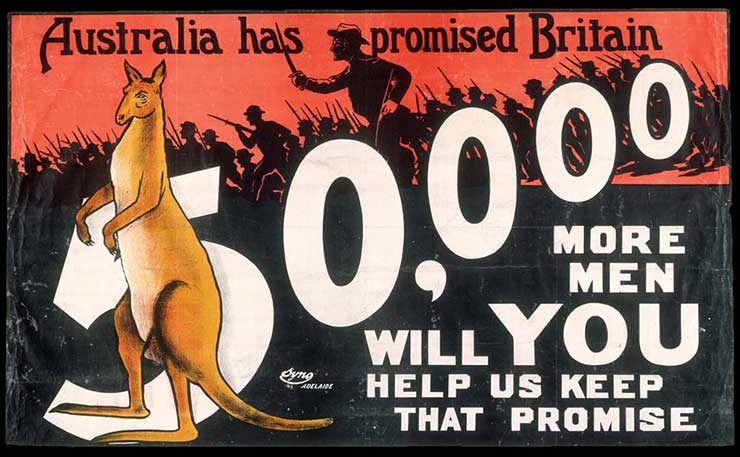

Nearly 300,000 men had volunteered in the first two years of the war, but according to the then Labor prime minister, William Morris Hughes, if we were really pulling our weight, the AIF would have half a million men in uniform.

As it was, volunteer recruits had fallen to 6,000 men a month and the generals were demanding 16,500 a month. To make up the shortfall, Hughes decided to ask the people to approve conscription.

He only asked because he couldn’t get conscription through parliament. There were enough pro-conscription Labor MPs in the House of Representatives who, in combination with opposition Liberal MPs, would have passed conscription in the lower house. Trouble was, Labor had 31 of the 36 senators and most of those were anti-conscription.

Blocked in the Senate, Hughes decided to hold a referendum with the aim of overwhelming the recalcitrant senators with a clear demonstration of the general will.

Hughes was supremely confident, telling the parliament on August 30, 1916, “I believe the Australian people will carry this referendum by an overwhelming majority”.

And The Little Digger had every reason to be confident. He was at the height of his popularity. Five of the six premiers, all the leaders of the opposition, all the major city daily newspapers, every celebrity in the sports and arts, virtually all church leaders, the masonic lodges, chambers of commerce and all the generals supported conscription.

The only major impediment was the Labour movement. During the first half of 1916, union and Labor party conferences had come out strongly against conscription. The Worker, the influential weekly of the Australian Workers Union, did warn Hughes before he called the referendum, “It has been decided already. The Labor movement has made its mind known.” The Union added that if he went ahead regardless, “it would be the greatest betrayal since Judas Iscariot”.

The reasons for the movement opposition were varied. Most believed the country was doing its share already and that if wealth was not being conscripted, why should workers be forced to sacrifice their lives. Some, like Henry Boote, the brilliant journalist and editor of the Worker, privately opposed the war as an imperialist one.

The initial response from some federal Labor MPs was that conscription was not a proper subject for a referendum. As Frank Brennan, the first MP to respond in parliament to Hughes’ announcement of the poll put it, “There are questions upon which a majority, however large, has no right to coerce a minority however small”.

Boote put it more poetically: “You cannot, by counting heads, dispose of a question that belongs to the province of the soul. In this respect, the personal will is supreme and sacred.”

Whatever their arguments, the anti-conscriptionists struggled even to be heard. Their publications were censored and confiscated; their offices raided and military censors installed; their publicists and speakers fined and sometimes jailed (including the future Labor prime minister John Curtin).

Squads of patriots and off-duty soldiers broke up their attempts to hold meetings on the Domain in Sydney and the Yarra Bank in Melbourne – the traditional free speech forums.

Even in a militant Labor bastion like Broken Hill, the first street meeting of the anti-conscriptionists was violently dispersed. However the next night 10,000 people were mobilised to protect the antis’ meeting and the streets of the Silver City were never again ceded to the patriots.

Something like this had to occur in the capital cities too. The turning point in Sydney came when the Labor party sponsored a ‘No’ meeting in the Domain. Such was the turnout and the success in protecting the platform from the super-patriots that Boote boasted in the Worker that the meeting was “the greatest gathering of men and women ever witnessed in Australia in the whole course of its history…. We only wish that William Hughes had been there. It would have been the end of his coquetting with the capitalistic Potsdammers of this country”.

The next morning’s newspaper reports would, in Boote’s view, have been sober reading for the “bald-headed Prussians of suburbia”.

The big rallies should not obscure the scores of smaller meetings. The whole campaign was the most Athenian moment in Australian history – a time of real participatory democracy. The Worker for October 16, for instance, lists no less than 87 ‘no conscription’ public meetings to be held in the following week in NSW country districts alone.

The ‘Yes’ side had its enthusiastic gatherings too, even if the audiences were distinctly middle class. Boote described the audience at one of Hughes’ Sydney Town Hall meetings as “the habitués of the golf links and the bowling greens, bald-headed fire-eaters over military age, a sprinkling of Labor renegades, the rag-tag and bobtail of Sydney’s snobocracy, and all their sisters, cousins, aunts, and poor relations”.

There was even a ‘terrorist’ scare during the campaign when 12 members of the anarcho-socialist Industrial Workers of the World were arrested and charged with sedition, sabotage and arson (a handful of warehouses in Sydney had been torched in suspicious circumstances). Their trial opened before the referendum and Hughes linked the accused to leading Labor anti-conscriptionists.

How then to explain the defeat? Hughes fumed in private that it was due to syndicalists, IWW revolutionaries, Sinn Fein-ers or Irish Australians in general, shirkers, red raggers and selfish farmers. Allowing for the colour, he was right – almost.

Historians of the left, right and centre agree that the ‘No’ victory was mainly a victory for the Labor movement. The brilliant journalism of Boote, the activism of the Left and the fear of ‘coloured’ workers replacing conscripts all played their part in mobilising the movement.

The word ‘movement’ is deliberately chosen as most of Labor’s parliamentary leaders campaigned like Hughes in favour of conscription. For this ‘betrayal’ these leaders were either expelled or forced out.

But it was not the Labor movement’s victory alone. In the general election held six months later the anti-conscriptionist Labor party received 44 per cent of the votes. If that represented the bedrock Labor ‘No’ vote and the ‘No’ vote in the referendum was 52 per cent, where did the additional eight per cent come from?

The traditional answer to this question has been the farmers. Enough of them, anticipating a good harvest and facing labour shortages, decided to vote for their economic interests. Doubt has been recently thrown on the strength of this by Professor Murray Goot who points out that the rural vote against conscription was only 1.3 per cent higher than in the cities. And who is to say this was due to farmers rather than rural or town workers?

The influence of Daniel Mannix, the Catholic archbishop of Melbourne, can sometimes be mentioned too. But as B.A. Santamaria, his most devoted disciple, has pointed out, Mannix scarcely intervened in the 1916 referendum (the 1917 re-run of the conscription referendum was a very different story). Besides, Irish-Catholic Australians were solidly pro-Labor and the British suppression of the Easter uprising in Dublin would have only made them more anti-conscription.

The extra votes to secure the ‘No’ victory, Goot speculates, may have come from the female half of the electorate. The reasoning goes something like this: we have a big sample of male voters in the soldiers of the AIF. They voted 55-45 per cent in favour of ‘Yes’. In order to counterbalance this male favouring of conscription and give the ‘No’ side its victory, women must have voted even more strongly for the ‘No’ side than the men for the ‘Yes’ side.

Of course, this is speculative (and Goot doesn’t put it higher than that). There were no exit polls back then. What is incontestable is that in the midst of war Australians refused to give their rulers the power to compel men to kill or be killed. And the refusal was repeated 14 months later in a second referendum.

Australia was the only sovereign nation in the war not to adopt conscription – probably because it was the only one to ask its people.

It is a comment on our age that the only significant institution to celebrate this signal event is Australia Post – with a special stamp.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.