Australia is still behind the times when it comes to accurately recording the details of someone’s birth, writes Penny Mackieson.

What is the primary purpose of a birth certificate? The answer to this fundamental question is constantly overlooked or confused in several current debates, especially as discussed by mainstream media.

Birth certificates are used for a number of purposes and there appears to be a lack of common agreement, and also of satisfaction, in relation to this. Indeed, the purpose of a birth certificate, the information that should be contained in it and for whose benefit, are all currently being questioned.

Most Victorians would probably assume that a birth certificate is a legal record of the facts of a person’s biological parentage and birth. In reality, for most people it is.

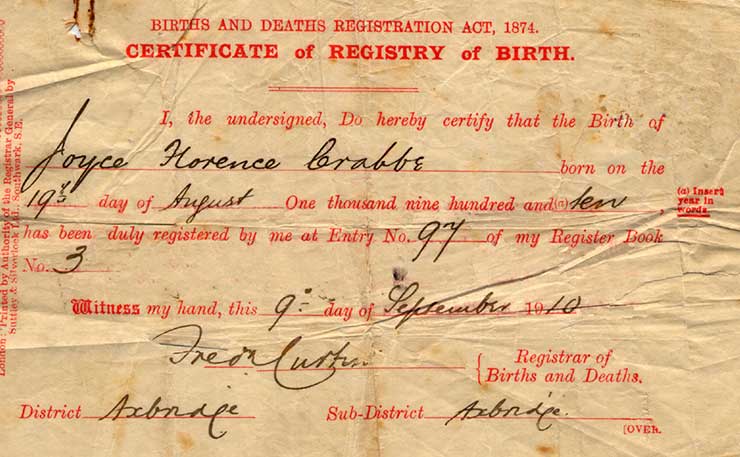

Yet, if it is accepted that the primary purpose of a birth certificate is to indicate who a person’s parents are, it is clearly inaccurate and overly heavy-handed to remove the details of a child’s biological parents from their birth certificate in order to name their legal guardians – as occurs in the case of adoption.

Whether made under open or closed arrangements, before or after the Victorian Adoption Act 1984, adoption in Victoria results in mandatory cancellation of the adopted person’s original birth certificate and issuance of a new one with a new name – as if she or he were naturally born to their adoptive parents.

One set of facts is replaced with another when, in reality, the facts of a person’s biological parentage do not change, even if their legal guardians do.

Further, issuance of a new birth certificate on adoption violates the adopted child’s universal rights, as enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, to preservation of their identity, name and family relations (Article 8).

From this perspective, the Victorian Government’s ‘same sex adoption’ legislation broadens the opportunity for violation of children’s rights in the same way that heterosexual adoption does. Both violate the child’s best interests being treated as paramount (Article 21).

Alternatively, if the primary purpose of a birth certificate is to reflect a person’s identity, including as it evolves across their lifetime, then the argument that transgender people should have the right to alter the ‘sex’ status on their birth certificates should be supported.

Notwithstanding, this argument seems to conflate the ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ of the person who is the primary subject of the birth certificate, thus these definitions require further clarification.

Further, if the primary purpose of a birth certificate is to reflect a person’s identity, it is unclear why the Victorian Government has not prioritised implementation of an integrated birth certificate (that is, a birth certificate which includes details of both the adopted person’s biological parents and their legal/adoptive parents) for those people adopted as children who want one, as recommended by the Senate Inquiry into Forced Adoptions in 2012.

Many adult adoptees look forward to having an official document that validates who they are – without having to seek dissolution of their adoption in the courts. These people were never in a position to consent to their biological identity being legally wiped away and the subsequent fragmentation of their identity is a lifelong challenge, including a source of re-traumatisation every time they are required to produce their state-falsified birth certificate as proof of identity – just as it is for many transgender people whose ‘sex’ as recorded on their original birth certificate does not match the ‘gender’ they identify with.

It is often difficult to determine the right legislative changes to make, particularly in regard to matters as complex and emotive as adoption, assisted reproduction, and equality for LGBTI people. However, Victoria’s legislation governing treatment of adopted people’s birth certificates was carried over from the secrecy and shame of the closed/forced adoption era, and it is time for this to change.

VANISH, the Victorian Adoption Network for Information and Self Help, has outlined its concerns and recommendations in regard to birth certificates, and many other matters associated with adoption, in its verbal and written submissions to the Victorian Law Reform Commission in the context of the latter’s current review of the Adoption Act 1984.

These concerns and recommendations are informed by 27 years of providing services to many thousands of individuals affected by adoption.

More fundamentally, VANISH is seeking the development of a clear position by the Victorian Government that answers the question: What is the primary purpose of a birth certificate?

We believe this will facilitate the harmonisation of laws in relation to adoption and assisted reproduction, including surrogacy, and help prevent the introduction of further inconsistent, and sometimes contradictory, laws.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.