Modelling released this week on the Australian Government’s plan to tackle climate change is not exactly what you might term ‘inspiring confidence’, writes Thom Mitchell.

In August 1990, journalist Kerry O’Brien anchored a segment on the then-new “burning issue”. Climate change. Four Corners viewers were told that the very “survival of the planet itself” was being threatened. This was urgent. It couldn’t wait.

The Hawke Government had just joined an emerging international movement, agreeing in-principle with the Toronto Agreement. Australia would aim to shave 20 per cent off its carbon emissions by 2005, over a period of just 15 years.

In the end, caveats were cashed, and literally nothing was achieved.

It seems ironic now, though, that even then O’Brien was identifying “a bankruptcy of effort in real terms”. In the 15 years since that broadcast, emissions have not declined. Even today, Australia is bereft of a fully-formed climate policy, and the odds of a disastrous repeat seem worryingly short.

Our form is bad. Australia has almost the highest per capita emissions of any developed nation. We export vast amounts of carbon each year. In 2014 Australia’s emissions pegged up for the first since their historical peak in 2005, and the rising trend continued through 2015.

In real terms, outside of the tricky numbers game of international agreements and carbon counting, analysts have warned that Government figures put absolute emissions on track to be up 6 per cent on 2000 levels by 2020.

Yet we’ve been told – incessantly, by former Environment Minister Greg Hunt – that we are “on track”. We’ve been told that we will “meet and beat” our current international commitment, to shave 5 per cent off 2000 level emissions by 2020.

That’s true – within the technocratic matrix of international carbon accounting – but it smacks of a bureaucrat’s victory, while overall annual emissions continue to trend the wrong way. According to analyst Hugh Grossman, from today’s emission levels, “we’ve still got emissions growing by around about 9 per cent through to 2030”.

Grossman is the Executive Director of energy analytics firm Reputex, a division of ratings agency Standard & Poor’s. In a White Paper published this week, the group found that on current policy settings, emissions would be just 2 per cent lower in 2030 than they were in 2005.

It’s a far cry from being ‘on track’ to meet the 26 per cent cut the Coalition pledged to achieve by 2030 at the climate conference in Paris last year. If we’re going to meet that target, much of the policy development is yet to be done.

In its analysis, Reputex modelled two very different options for how the Coalition’s policies could be used to meet the 2030 target (more on that later). Their scenarios are extreme, because they’re academic.

We actually don’t know that much about how the Government will lash together their raft of policies, which has been passing for a climate platform since Australia’s 2030 targets were announced last year.

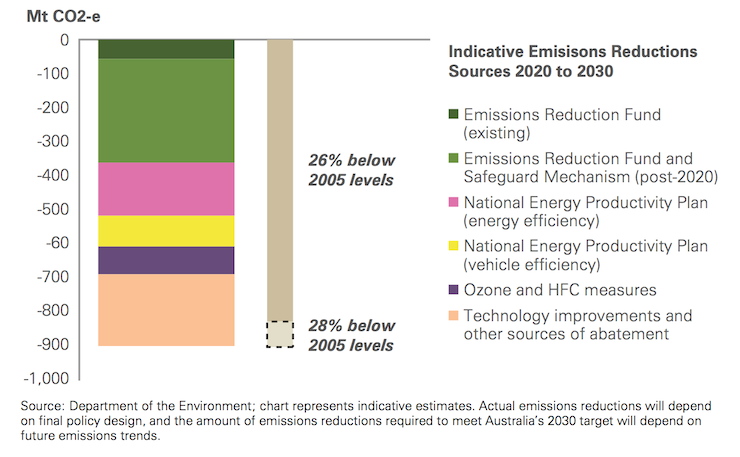

At the time, the then Environment Minister Greg Hunt wheeled out an interesting graph. Inset below, it’s useful, here, in illustrating how much of the decision making had been pushed back.

The different coloured wedges represent initiatives which it’s hoped will deliver certain emissions reductions. The tiny sliver of dark green shows what the $2.55 billion budgeted for the Emissions Reduction Fund to 2020 will buy.

The vast bulk of the emissions reduction needed to hit our 2030 target have been shrugged off for now. Some of the initiatives, like the National Productivity Plan to improve energy efficiency by 40 per cent over the next 15 years, hold plenty of promise. But the detail on how the government’s various initiatives will actually work to achieve emissions cuts is still being developed. It all depends, apparently, on “final policy design”.

“They’ve outlined a framework from which these ‘indicative emissions reductions’ would come. That’s what the chart from Greg Hunt’s office refers to. That’s all they’ve tabled,” Grossman said.

“There certainly comes a point in time where they need to attach some detail to the underlying settings by which you achieve those numbers.” Certainly. The future of the Emissions Reduction Fund – represented on Greg Hunt’s graph by a large chunk of light green – is particularly important.

Broadly, the Fund works to facilitate a ‘reverse auction’ in carbon emissions. It opens the public purse strings, and puts taxpayers’ dollars to use in paying polluters as an inducement for them to pollute less.

Unfortunately, like so much Australian climate policy, the Emissions Reduction Fund is running only half-cocked. Lying dormant within it is what’s known as the ‘safeguard mechanism’, which is supposed to set an emissions baseline for big polluters, and over time force them to buy ‘offset’ carbon credits if that limit is breached.

Right now, it’s effectively redundant. On current settings, none of Australia’s top 20 emitting facilities would incur any liability as a result of the safeguard mechanism, despite almost all being forecast to grow their emissions over the next decade.

In other words, the Government has been handing out billions of reverse-auction carrots, but not touching what little stick the Emissions Reduction Fund provides for. The policy has already chewed through three quarters of its initial $2.55 billion budget, but it’s paid for only a small dark green slither on Greg Hunt’s graph.

With much higher emissions reduction targets for 2030 looming, you can see how costs might spiral out of control if the safeguard mechanism doesn’t set genuine emissions baselines to either keep companies’ pollution down, or force them to offset it.

The revamped Emissions Reduction Fund is supposed to pick up around half of the emissions abatement task to 2030, so the safeguard mechanism will need to be put to use. We’ll have to wait until after the 2017 review to see what that looks like… and most likely longer to see a coherent and detailed package of climate policy.

In its analysis, Reputex played around with the government’s options, to produce models that explore a couple of possible policy mixes.

The first scenario assumed the safeguard mechanism would keep on as it is. That it would be toothless, and the other wedges on Greg Hunt’s graph would do all the lifting. Grossman said that to hit Australia’s 26 per cent target for 2030 emissions, without using the safeguard mechanism: “You would need to see around about a tripling in ERF funding, a tripling of take-up of solar PV from current levels, and about a doubling of energy efficiency and vehicle efficiency take up from today’s levels.”

Conversely, the second assumed that the safeguard mechanism would be aggressively ramped up so that it covered the whole emissions reduction shortfall in Reputex’s model. In that scenario, the safeguard ‘baseline’ would need to ratchet up at the heady clip of 5.4 per cent each year between 2020 and 2030 (a thought that would presumably raise Business hackles).

Obviously Reputex’s models represent two extremes. The policy will be some kind of actual mix between the two. “The issue is trying to find [a path] somewhere in the middle, which would probably represent more of an integrated solution that more fairly balanced emissions reductions across the economy,” Grossman said.

Along with their White Paper, yesterday, Reputex launched a new tool to help in exploring these combinations. There is a free version. It’s open to the public – or, you know, the good folks in Environment Minister Josh Frydenberg’s Office….

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.