Unemployed people in Australia are finding it increasingly difficult to hold their job agencies accountable for mistreatment, stand-over tactics and poor performance, writes Owen Bennett.

When Paul Scerri’s contract ceased at his workplace in early 2015, he was without gainful employment for the first time in his adult life.

After his employment connections fell through, Melbourne resident Scerri, 36, was left with no choice but to apply for the unemployment benefit.

Making a bad situation worse, Scerri’s marriage was breaking down leading to what Scerri describes as a “messy divorce”.

Like so many Australians sacked by their employer, Scerri was hopeful that his recent employment experience would quickly lead to a new job.

With the added assistance of regular interviews with a privately run job agency – a requirement expected of all Australians on the dole – Scerri was expecting his time on Newstart to be short-lived.

However, soon after registering with his job agency Max Employment – a US-owned billion-dollar company – Scerri had to quickly revise his expectations.

“When I approached Max Employment about helping me find work, it became pretty clear that they weren’t really interested”, says Scerri.

Under the Government’s four-year $6.8 billion jobactive system, employment services like Max Employment are required to assist “jobseekers canvass the jobs in the local labour market”, help them “prepare a resume”, and “refer them to suitable job vacancies”.

Additionally, the Government provides job agencies with an “employment fund” of $300-1200 in order to help “job seekers with work related tools, skills and experience”.

With the current government statistics indicating that there are more than 18 job seekers competing for every listed job vacancy, this support can be the difference between becoming long-term unemployed and finding work quickly.

Scerri maintains that Max Employment failed to uphold these obligations.

“In all my time with Max, they did not help me get even one job interview”, says Scerri.

When Scerri finally managed to get a job at the Melbourne Airport – without any assistance from Max Employment – he was denied much needed travel assistance from his Employment Fund.

Six months of living off the meager Newstart payment – roughly $390 below the poverty line per fortnight – had left Scerri unable to afford petrol for the two-hour round trip to and from his workplace.

With public transport to the Melbourne Airport not an option, Scerri approached Max Employment about getting travel assistance from his Employment Fund.

“I asked them for 7 days worth of petrol vouchers, but Max only gave me $25. It was no way near enough”.

Unable to get to work, Scerri had to explain to his managers that he had no way of getting to work. Scerri lost his job.

“Because of Max Employment I lost my job. Not only did they fail to help me find work they actually cost me my job.”

Outraged at his treatment, Scerri decided to confront Max Employment about their failure to keep their end of the bargain, known as ‘Mutual Obligation’.

“They kept telling me about my mutual obligation requirements to go to regular appointments and activities. But when I told them about their mutual obligations they became very rude and threatening.”

Scerri called the Department of Employment’s National Customer Service Line to make an official complaint, leading to a bitter six-month dispute.

After many phone calls, the Department informed Scerri they had contacted Max Employment about the issue and were satisfied with their response.

When Scerri requested to know the details of Max Employment’s response, the Department of Employment refused and directed Scerri to request the information under the Freedom of Information laws. Scerri immediately requested the documents but is still waiting to receive them.

The Department of Employment informed Scerri that if he was unhappy with how Max Employment had treated him, he should simply change to a different employment agency.

“The Department kept saying that I should just move to another job agent if I was unhappy. But I was also told that if I did that I would not be able to pursue my complaint against Max. Basically they were saying, ‘if you don’t like how you are being treated, find another provider. Otherwise there is nothing we can do’.

This tactic only made Scerri more determined to make sure his complaint was properly investigated.

“It was clear that they were more interested in protecting the job agencies than helping me launch my complaint. I thought, ‘if I don’t complain, then who will?’ I needed to do it not just for me, but for everyone.”

In response to the Department of Employment’s refusal to properly investigate his claim, Scerri decided to take the issue to the leading Government watchdog, the Commonwealth Ombudsman.

In response, Max Employment took its intimidation tactics to shocking levels.

“Max knew that if they forced me to change to a new job agent, the Department would no longer investigate my complaint. That’s when they started coming down on me really hard”, said Scerri.

Max Employment demanded that Scerri attend a tough new regime of activities and appointments.

For his Work for the Dole activity, Max Employment insisted that Scerri must pick up used syringes on a busy metropolitan freeway.

“It seemed like a really unsafe activity and took me away from looking for jobs, so I refused to participate”, said Scerri.

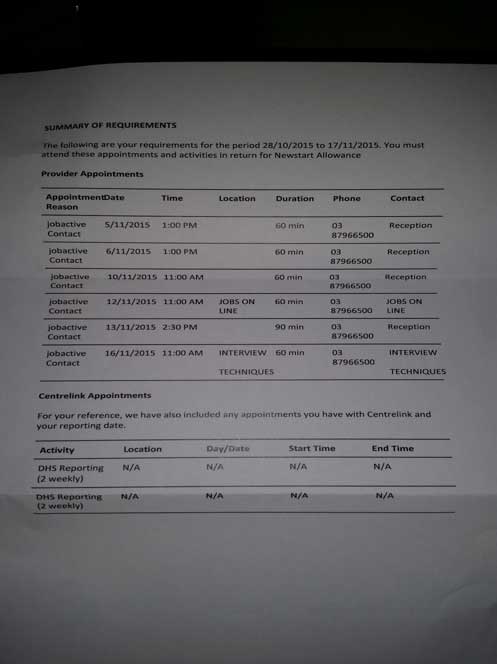

In a letter sent to Scerri on the 28th of October 2015, Max Employment stated that in order to continue to receive Newstart payments Scerri must attend a total of six appointments (totalling six and a half hours) over an 11-day period.

Each month Newstart recipients are required at a minimum to attend one appointment and apply for 20 jobs.

By requesting that Scerri attend more appointments than he was obliged, it appeared that Max Employment were using its position of power to cynically manipulate the situation to its benefit.

“They just kept coming at me with these sorts of bullying tactics in the hope that I would change to a new provider and drop my complaints. How many other people they and other job agencies must have done this to?”

Max Employment also denied Scerri’s request for assistance in obtaining counselling services.

“They told me that they would not provide any counselling services and that I should just ‘man up’”, says Scerri.

Looking for help, Scerri then joined the Australian Unemployed Workers’ Union (AUWU), an organisation committed to fighting for the rights and dignity of unemployed workers. Max Employment again resorted to intimidation tactics.

“In one of my conversations with Max, I told them that I was going to be attending an Australian Unemployed Workers’ Union protest which was being held out the front of a Max Employment-sponsored $650-a-head conference into long-term unemployment. I was warned that if I attended that conference I would be heavily sanctioned.”

Concerned that Max Employment would financially penalise him for attending the protest, Scerri decided not to go.

Scerri made sure to keep the Commonwealth Ombudsman informed about the stand-over tactics employed by Max Employment.

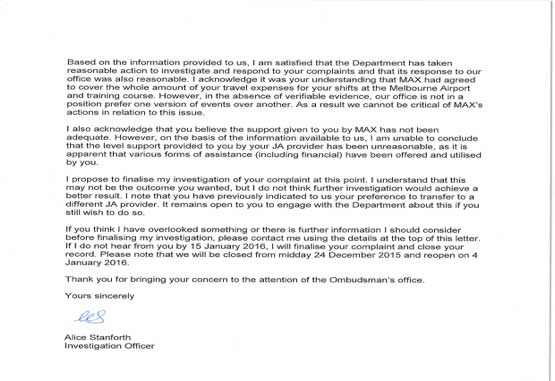

On 22 December 2015, the Ombudsman finally concluded their 6-month long investigation. A Commonwealth Ombudsman Investigative Officer sent Scerri a letter stating that they were “satisfied the Department took reasonable action to investigate and response to your complaints”.

The officer explained that in the “absence of verifiable evidence, our office is not in a position [to]prefer one version of events over another”.

Scerri was crushed.

“After going to all these lengths to defend myself against Max, it is demoralising to be told it’s your word against theirs.

“What I’ve learnt through all this is that no matter what kind of unfair treatment you have put up with, there is no use complaining. They are billionaires and you are nothing. It doesn’t work when you complain to the Department of Employment or the Ombudsman. How can you ever win?”

Paul Scerri is not alone. Every day the Australian Unemployed Workers’ Union receives fresh cases of people being mistreated by job agencies who are consistently failing to provide the services they are paid by the Government to perform. As a result, complaints about job agencies have reached record levels under the jobactive system.

With the Turnbull Government trying to give employment services industry unprecedented new powers to financially penalize unemployed workers, the established culture of fear and intimidation pervading the employment service industry is showing no signs of going away.

Already, job agencies have the power to fine unemployed workers 10% of their Newstart entitlement – and a further 10% each day until they ‘re-connect’ – giving the unemployed no chance to appeal against the fine before the penalty amount is taken away.

The longer the Government refuses to properly regulate the employment services industry, the more we will see cases of unemployed workers like Paul Scerri being mistreated.

With a recent report showing that one in four unemployed Australians have been forced to beg on the streets for more than a year, and more than half forced to approach a charity for help, it is clear that a social disaster is looming if the Government does not take strong action to curb the culture of lawlessness pervading the employment services industry.

* To help regulate the dysfunctional employment services industry, sign the AUWU’s petition calling for the establishment of an independent ombudsman to regulate the industry and handle complaints.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.