With its hands-off approach, the Coalition is charting a course straight for economic disaster, writes Ian McAuley.

Most media reaction to Tuesday’s cut to official interest rates has taken a “what’s in it for me” line, focusing on the banks’ failure to pass on the full 0.25 per cent cut to borrowers.

Those who are heavily in debt will enjoy a little relief, until they come to realise, as many economists do, that it is an act of desperation – an attempt to stimulate an economy that’s probably heading to recession.

The downside for borrowers is that the cut is driven, in part, by low inflation: CPI inflation for the last twelve months has been only 1.0 per cent. In a period of reasonable inflation most people can rely on increases in nominal incomes, which means the burden of their mortgage debt (fixed in dollar terms) reduces over time. But when inflation is low, and when incomes are struggling to keep up with inflation, the mortgage hangs around like a house guest who outlives his welcome.

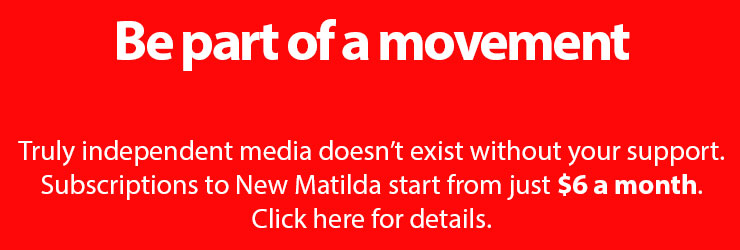

As economists put it, what counts for borrowers is the real interest rate, which is the nominal rate (as charged by banks) minus inflation, and over this century so far real housing interest rates have been consistently around 4.0 per cent, as shown in Figure 1. Even if the banks were to pass on the full cut there would be no effective relief from the mortgage repayments.

The really bad news is that the need to cut the interest rate to such a low level is a sign of economic policy failure.

It’s worse than the failure resulting from a sudden shock such as the financial crisis of 2008. Rather, it’s a failure in the government’s neoliberal economic philosophy, a philosophy embraced by both major parties, but with missionary zeal by the economic decision makers in the Liberal Party – Finance Minister Mathias Cormann, Treasurer Scott Morrison, and newly-appointed economic adviser to the prime minister, Peter Hendy.

The core of that philosophy is that governments should get out of the way and let the private sector flourish, exemplified by the Coalition’s proposal to cut corporate taxes, even though our taxes are very low for a ‘developed’ country. Governments should run a balanced budget if possible but in times like the present, in the wake of the GFC, a deficit is to be tolerated if it helps keep the economy out of recession (and if it has been necessitated by abolishing Labor’s evil “anti-business” taxes such as the carbon tax).

In fact, to hard economic conservatives, counter-cyclical spending is the only valid reason for public spending, because, as implied in the Liberal Party’s statement of beliefs, all public expenditure is wasteful. It doesn’t really matter whether it’s spent on a submarine, a hospital, or a new stadium in Toowoomba, because “businesses and individuals – not government – are the true creators of wealth and employment”, to quote from that document.

If possible, the task of stabilising the economy should fall primarily to monetary policy, through the actions of the Reserve Bank. It’s a “hands off” approach, relying on the availability of cheap money to stimulate households to spend and businesses to invest when the economy needs a boost.

When the Reserve Bank lowers interest rates, those lower rates should pass through to the finance sector, encouraging businesses to borrow for investment in plant and equipment, thereby stimulating economic activity and providing employment. That’s the essence of monetary policy.

The trouble is that the model is a fantasy. Low interest rates haven’t worked in other countries and they aren’t working here. Businesspeople don’t invest unless they see a demand for their products and unless they perceive some policy certainty in the near future.

That’s why over the financial year just past Australia’s large public companies have handed back to shareholders around 70 per cent of their profits as dividends, rather than re-investing. That’s why banks have been applying some of their profits, and will use some of the cut in official rates, to reduce their debt exposure, as a buffer for possible hard times ahead.

The simple story is that the world is awash with money in the hands of would-be investors, many of whom are metaphorically putting it under the bed, or are bidding up asset prices, particularly established housing in Australia’s case.

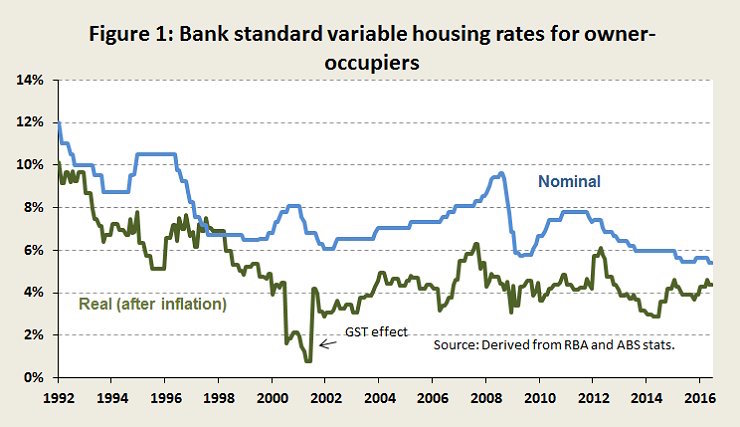

Figure 2 shows the inflation-adjusted rise in established house prices over the last 30 years, focusing on Sydney and Melbourne, which are now two of the world’s most overheated housing markets. We’ve been experiencing inflation, but it’s been asset price inflation rather than traditional commodity price inflation.

As anyone who looks around our capital cities can see, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne, there are lots of new apartments and lots of cranes on the skyline building new ones. And in the far outer suburbs new developments are proceeding apace. Some day this will end in tears for heavily-indebted people – often tradespeople on modest incomes, as the Coalition reminded us during the election – who have bought into a market that’s been rising for 30 years.

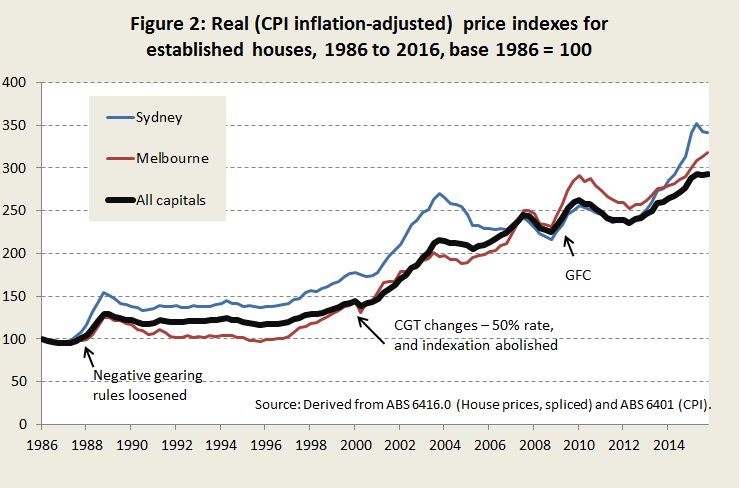

All that speculation has been financed by debt. Household debt has been rising for many years. It plateaued for a little time following the financial crisis of 2008, but since the RBA has been lowering nominal interest rates it has been rising once more.

The most serious aspect of this rise in household debt is that it feeds into foreign debt. Although households borrow on the domestic market, our banks borrow on world markets, and while partisan comment has been about government debt (which is low by world standards), our main problem is foreign debt, now more than a trillion dollars.

That’s the debt to which Standard and Poors was referring last month when it suggested our AAA credit rating was at risk. Over-zealous journalists who seem not to have read the S&P report said it was about the need for “budget repair”, but while S&P does mention the issue of our fiscal deficit, their prime warning is about foreign debt, and their report doesn’t use the emotional and partisan term “budget repair”. Rather it emphasises our “high external and household indebtedness”.

To remind us of our foreign indebtedness, on the same day that the RBA lowered interest rates the ABS announced another high trade deficit, bringing our national deficit on current account to $36 billion for the year just past.

True to form Treasurer Morrison brushed aside any suggestion that the rate cut may be a sign that the economy is in trouble, but the defensive tone of his response reveals his lack of conviction.

We cannot expect the rest of the world to go on lending to us to finance housing speculation.

It’s hard to predict when our day of reckoning will come or what form it will take. Offshore commentators, detached from our partisan prejudices and bullish overconfidence, are sounding warnings. BT’s Vimal Gor suggests Australia is heading to a South American style currency crisis. Steve Keen, of London’s Kingston University, predicts a 40 to 70 per cent fall in house prices and a sharp rise in unemployment as soon as next year.

It’s easy to heap scorn on such commentators when their predictions fail to materialise, but their main error is that, as sober and intelligent people themselves, they underestimate the capacity others have to go on irrationally buying into a rising market. Their warnings are like parents’ warnings to teenagers driving dangerously: the longer the teenagers get away without an accident or serious conviction the more their overconfidence is reinforced and the more they dismiss their parents’ advice.

It’s not too late for the government to stave off a recession. A fiscal stimulus is in order, but of course we are already running a fairly high deficit. The trouble is that it’s the wrong sort of deficit, because it’s directed to current spending rather than capital investment.

We cannot go on running a deficit to finance current government spending, and therefore the government should raise taxes – a carbon tax, an inheritance tax, a tax on family trusts, and reform of capital gains and superannuation taxes as starters. Taxes with minor immediate impact but which slowly build up to collect more revenue would be ideal, in that they would not dampen our present need for fiscal stimulus while giving reassurance that we are serious about responsible financial management.

At the same time, we could provide a strong fiscal stimulus with an ambitious capital works program. After decades of neglect of government capital investment there are plenty of opportunities for productive investment – proper broadband, urban public transport, interstate highways and railroads, protection against climate-change related storm damage to name a few. (Treasurer Morrison is right, we need investment, but he seems to be incapable of understanding that well-directed public investment can be even more productive than private investment.)

That way money could be directed to real investment rather than being cycled through the real-estate market, strengthening our public balance sheet and, to borrow a slogan, providing “jobs and growth”.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.