Democracy was designed to work for the masses. We don’t live in a democracy anymore, writes Mike Dowson.

Olives. That was when the penny dropped for me.

Have you ever considered the range of products in the supermarket? The shelves are full of options. But look closely and you notice the smoke and mirrors.

I realised this in front of the olives. There exist numerous olive varieties, many grown in Australia, and there are different ways of preparing them for consumption. You can travel the world with the olive.

But the supermarket only sells a few kinds. The diversity is in the branding, packaging and inexpensive flavour additives. Behind the shelves is a supply chain designed to maximise profit for the retailer. Choice is largely a marketing illusion.

The same can be said of another of our duopolies, our political system. This is hardly a new analogy. Among journos it’s an old joke. But it is increasingly an impediment to our fortunes.

Over the years, policy platforms have converged toward a narrow set of goals. Once an idea takes hold, both parties adopt it as scripture, and the media behave like priests of the order. This is how the budget surplus – a mundane lever of economic management – became a kind of holy grail.

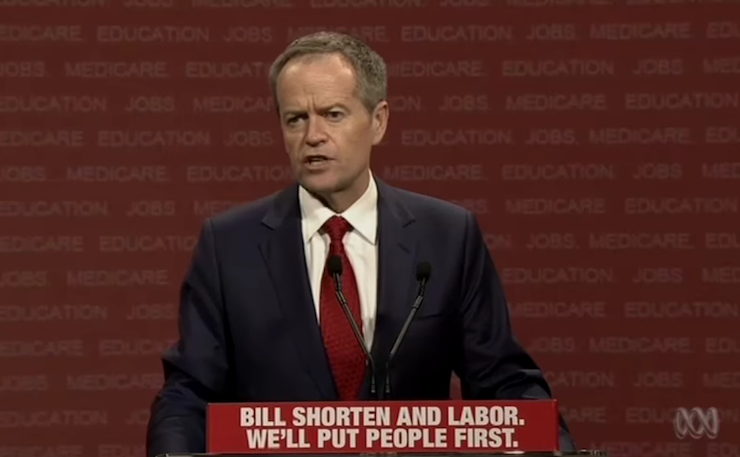

What’s left of vision subsists in slogans. Voters are lured with branding and special offers. Tax and spending are wielded like loyalty programs for core constituencies.

Praising democracy, Abraham Lincoln said you can only fool all of us sometimes, and only some of us always, but then the spin doctors realised that’s all they need to do.

Few living Australians have ever experienced economic decline, or a genuine threat to our democratic sovereignty. We have enjoyed a long period of prosperity and stability, almost unknown in any other time or place. It is therefore difficult to imagine epochal change. And hard to see what difference good government makes.

From election to election, the tides of politics have ebbed and flowed, leaving layers of policy sediment on the bedrock of social democracy, while the ship of growth has chugged reliably along.

This period is drawing to a close.

Another election has come and gone. The major parties have bickered again over ideology. There is nothing in the new government’s agenda that lights the way ahead. To our fears for the future, it offers paternalistic reassurance.

We are running on autopilot. The lines on the graphs may flicker, but they will not long deviate from their inexorable trends. The forces that are driving them lie outside the narrow frame of current policy debate.

This is disturbing, because the trends in the data are clear, and they are not encouraging.

Fewer well-paid jobs. Fewer opportunities for small business. Fewer family farms. Less investment in the productive economy.

More debt, more poverty, more homelessness, more sick children, more extreme weather events, more environmental degradation.

It’s strange, don’t you think? Human beings have accomplished so much. We have advanced technology, brilliant scientists, talented, educated, energetic young people. Why don’t we do something?

It’s as if there is an invisible hand holding us back.

In fact, I believe there is.

Once, in a time before we knew about climate change, economic growth was the unquestioned solution to need, and capital and labour were equally important to it. Our two-party system formed around these apparently opposing interests, but both parties had to accommodate them.

As long as the benefits of growth were distributed through adequate wages and social services, the lives of ordinary people improved. The rich still got richer. They just had to share.

Then the tide turned. As businesses gobbled up competitors and market share, and automation and globalisation diminished the power of labour, wealth began to gravitate upward again. Both major parties leaned further toward the interests of capital.

Today, through donations and lobbying, a handful of companies – the banks, miners, fossil fuels, supermarkets, developers – and the business lobby generally – dominate our parliaments. Grass-roots party membership has declined along with its influence. The character of our politicians has changed as a result.

It’s fashionable now for politicians to label their opponents ‘out of touch’. This is ironic. The writer Jason Wilson recently made the case that we have a governing class drawn from law, consultancy, and the upper echelons of business, that is almost universally out of touch.

The revolving door at the end of politics leads back to lucrative private sector jobs. Many politicians are also big property investors.

The new politics has come to resemble the market economy it espouses. Politicians are themselves like a marketing agency for the big end of town. Business tells government what it wants, and politicians sell it to us.

Previously we relied on the media to keep the bastards honest. But the mainstream media is now part of the same cartel. Ownership has been similarly consolidated. Stressed commercial outlets depend on business advertising and packaged news product. Our public broadcaster has been cowed.

This symbiosis of backroom politics and public relations has tarnished the democratic process. The public is smelling a rat. The spin doctors will be poring over the data looking for new angles.

If you’re underwhelmed by the olive shelves, you might wander over to the deli section. There you will see more of the same olives, but displayed in trays. For a small premium, you can enjoy the nostalgic experience of being served by a human being.

The supermarket is optimised to provide you with just enough choice, and just enough of a shopping experience, to make it unnecessary to go anywhere else.

And so it is with our politics. The weakness of the government’s mandate does not reflect a broad public appetite for change. Prosperous people want more of the same. But many are starting to doubt the ability of either party to deliver.

The truth is our governments had little to do with our prosperity. It’s easy to look good during a boom. Difficult decisions simply went on hold while China bought up everything in sight. Politicians concentrated on re-election. They squandered the proceeds on tax cuts, a housing bubble and wealthy superannuants.

Now the boom is ending, our economy is laden with electoral patronage and they don’t know what to do. Up to now, they didn’t need to know. There is no shortage of experts with good ideas. But our politicians haven’t had much time for experts. Numerous costly enquiries are collecting dust on shelves. They are left with a few flimsy tenets of ideology.

For decades, we have staked the future on growth driven by demand and investment from abroad. We supplied resources to global capital in exchange for jobs and taxes. Governments acted as matchmakers and then legislated themselves out of the equation. A whole generation of politicians has been groomed for the job of dispensing favours and convincing the rest of us that everything is going well.

Everything is not going well. The global economy is in trouble. Our economy is in trouble. The planet itself is in trouble.

This is one of those times when public relations won’t pass for leadership.

The beneficiaries of the boom years are growing old. A new constituency is emerging which is not well served by the status quo.

Rising house prices and falling wages may suit you if you’re comfortable and looking forward to cheap coffees, cleaners and care workers in retirement. But not if you’re young and aspiring, and those are your career opportunities.

It must be especially galling when your elders also propose to leave you with an environmental catastrophe they have conveniently ignored.

A system which pampers passive investors with bipartisan support, and stages mock contests over the leftovers for its productive workforce, is doomed to fail, even without the combined threats of economic decline and climate change. When a system is this unbalanced it must correct. The longer the imbalance persists, the more violent the correction will be.

How did it come to this?

The amazing fact is that no villainy was necessary. No evil genius had to orchestrate it. Politicians and influential people simply worked out mutually beneficial arrangements while the rest of us weren’t paying enough attention.

Our democracy is a sham. We have no say in the factors which most affect our future. Those are already decided. As our prospects dwindle, we are drawing straws for who gets sacrificed.

In a contest of self-interest, the rich and powerful will always win. Their lobbyists and strategists are at work every day. If we only stick our heads up every few years to vote on slogans, personalities, electoral bribes and scare campaigns, we lose.

This is not what our forebears fought for. The country didn’t flourish because interest groups lobbied effectively. It flourished despite that, because the majority demanded a fair go for everyone.

I still detect that spirit among ordinary Australians. But it is frustrated by a process which could just as effectively be decided by a coin toss. Democracy is not an occasional shopping expedition. When we demand more active participation in government, everything will change.

In Switzerland, citizens can challenge a law passed by parliament with a referendum. Would that encourage more care and honesty from politicians?

Victoria is using citizen juries to develop its infrastructure plans. As Ian Walker from the newDemocracy Foundation puts it, if we trust a jury to judge an accused person, why not a proposed law?

Political philosopher Piero Moraro advocates a form of plural voting, which grants more weight to the votes of those more affected by the outcome. What would be the result for climate change legislation, if young people had more say in it?

Economics correspondent Peter Martin makes the case for submitting policy costings to immediate public scrutiny, and splitting budgets into recurrent spending and investment spending. Perhaps then we could have an intelligent conversation about priorities.

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it”, goes the old saying. But what if it is broke?

Our political system was conceived in a time when a small, homogenous and largely rural population travelled by horse and buggy and communicated with handwritten letters. During a long period of good fortune, we didn’t require too much from it.

If you want to see what inequality can do, look ahead in the queue. In the US, PHD professors drive for Uber and collect food stamps. Millions of workers have lost their jobs and homes. Now the political establishment has a popular uprising to deal with.

In the UK, young professionals share rooms and travel long distances to the city to work. The government has been attacking public services as if they were a plague of vermin. Rising resentment has brought the chaos of Brexit.

You might consider alternatives, like some northern European countries. With far fewer natural resources than us, they work less hours, with generous social services. Contrary to the myth spread by the duopoly, multi-party governments seem to be able to get things done.

One change I have noticed amid the dull simulacrum of the supermarket is the appearance of the Sicilian Green. At some point the supermarkets decided its boutique popularity was worth stealing.

The Sicilian Green is a superior olive, with distinctive texture and flavour. The cost-cutting, value-capturing supermarket duopoly now offers some insipid examples of it.

If you want the real thing, you need to visit an alternative supplier who really understands and believes in the product.

Of course, if you’re flat out working, or just trying to chill out, you won’t have time to shop for specialty items. The supermarket is convenient. The products are near enough to the real ones. They’re counting on that.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.