Those worried about the impact of population growth on the environment should look at what’s on their plate first, writes Geoff Russell.

For as long as I remember, I’ve been against increasing our population. My partner and I worked out that the planet was overpopulated not long after we met; over 35 years ago. So we’ve never had children. I’ve met many people over the years who made the same decision for the same reason.

Shake any environmentalist of a certain age and the odds are that a copy of one or more Paul Erlich books will fall out; probably his The Population Bomb of 1968, or perhaps Population, Resources and Environment of 1970. The idea that we can increase our population exponentially indefinitely is about as dumb as an idea can be, but it doesn’t follow that all population growth is inevitably bad.

If you don’t know precisely what exponential means, then there’s a great series of video clips on Arithmetic, Population and Energy which explains it. They also explain the consequences of such growth. If numbers aren’t your thing, then here’s the one paragraph version.

Suppose a population grows at two per cent of its current number per year. So if you have 100 people in the first year, you’ll have 102, 104.04, 106.12 in the next three years. How many years before the population doubles? There’s a quick rule for calculating this. I won’t explain it, but if you divide 70 by the percentage growth each year, you get the doubling time. In this case 70/2 is 35. And if a population grows at 10 per cent per year, then 70/10 is 7 so the doubling time is 7 years. When a population is growing like this, how many doubling times before you have 1,000 times your original population? Just ten. So if the human population is a billion and growing at two percent per annum, then in 350 years (which is about the time since French philosopher Rene Descarte died) there will be 1,000 billion people on the planet … Ouch!

But exponential population growth is a convenient fiction which only ever holds briefly before resource limits kick in.

Many people, once alerted to the catastrophic consequences of exponential growth, start seeing population control as the answer to all problems. I certainly did after reading Erlich back in my school days. Groups like Sustainable Population Australia (SPA) seem to see population as the driver of all evil and there’s also a Sustainable Australia political party which has immigration cuts as core policy. It’s also common at any public meeting – on any issue at all – for somebody in the audience to blame any problem in the known universe on our rising population.

There’s always a subtle shift among population blamers from perfectly true claims about ongoing exponential population growth to something which sounds superficially similar; namely that more people is always bad because it inevitably means more resource use leading to more climate change emissions and horrible environmental consequences. Say it quickly and it sounds like a no-brainer.

It’s been a couple of hundred years since the best scientists started to test no-brainer claims instead of just accepting them; Galileo famously dropped stuff off the leaning tower of Pisa to test the no-brainer that heavy things fall much faster than light things; they don’t.

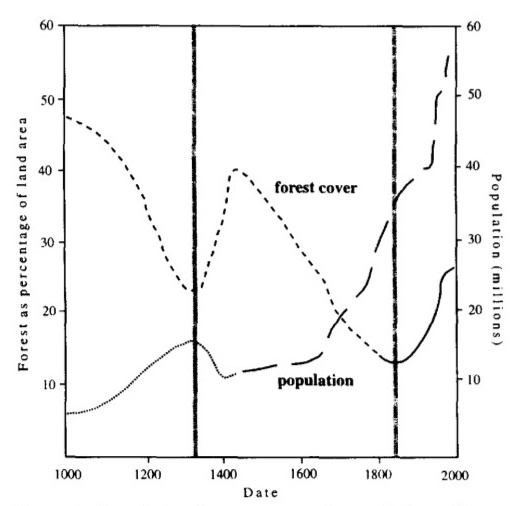

So consider this graph showing forest cover in France and population.

Look at what happens after 1830 … both forest cover and population rise steeply. How is that possible? In the US, forest cover has been roughly stable for the past 100 years despite a three-fold increase in population. The French case isn’t a fluke.

The no-brainer is false.

The graph is easily explained because technological change enabled more people to have a smaller impact. In this case, the magic bullet was coal. A small coal mine can yield more energy than a vast forest. Switching from burning forests to burning coal allowed forests to regrow.

But what about coal pollution? Wasn’t the technical fix bad because of that horrible added pollution?

No. Apart from the rather significant CO2 differences, smoke from both coal and biomass is similarly nasty. Indoor air pollution, mostly from burning wood, is currently a major global killer. The smoke from biomass burning causes about four million premature deaths annually among the three billion people who use it for fuel; many are children under five years old.

As an aside, it’s majestically ironic that one of the historical anthems of the anti-nuclear movement praised this annual source of four million premature deaths: … “Give me the comforting glow of a wood fire / But please take all of your atomic poison power away”. It’s actually nuclear power that’s been a major lifesaver (preventing some 1.8 million premature deaths) by displacing the burning of both coal and wood.

Burning bad, fission good.

The wood deaths, of course, may well be described as both sustainable and renewable.

The point I was making before the aside is that we shouldn’t let current lifestyles constrain our thinking. The influence of marginal increases in population, particularly here and now in Australia, is largely a matter of choice.

We can house and feed far more people than we have now while simultaneously reducing our environmental footprint and making our cities more livable, if we choose to.

Given our disproportionate per capita responsibility for destabilising the climate, I believe we have a clear duty to be thinking about how to deal with climate refugees. Some might also say that our role in the war in Iraq carries a similar responsibility. Either way, we can’t maintain our selfish splendid isolation forever. So how might we deal with some millions of climate refugees in coming decades? How might we make it a catalyst for improving our cities?

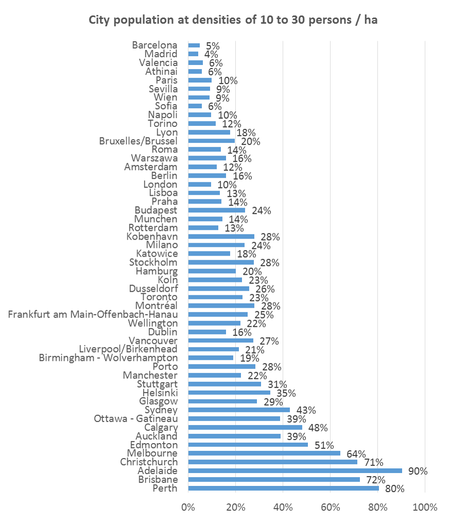

Consider housing. The following chart (source) comes from a fascinating transport blog:

You can see that only five per cent of people in Barcelona and 28 per cent of people in Stockholm live at the kind of densities common in Australian cities. Our sparsely populated cities don’t only cause urban sprawl, but their low density makes our cities more energy intensive and less livable. We travel further, using more fuel and spending more time in cars and traffic. That’s enough to make anybody angry.

Our sprawling cities make affordable and efficient public transport impossible. That chart and others in the source article make it clear that we could double the density of our cities without increasing their boundaries and without losing any embedded green space; do it right and we could also expand the number and size of parks and wildlife corridors in our urban areas. Increasing the density of our cities won’t be easy, but there are plenty of models; places where it has been done far better than here.

We should also recognise that while housing and cities are crucial to our daily lives, they aren’t the dominant impact on the environment as a whole.

What is?

Food choices, with daylight for second.

If you are sincerely concerned with biodiversity and wildlife habitat, then food choices are really the only choices which matter because our urban areas, as sprawling and ill-designed as they are, are less than 2 million of our 770 million hectare continent. Our dumps and mines are another 170,000 hectares.

We crop some 24 million hectares but it’s our cattle, chickens and pigs who eat most of what is produced. In addition to eating three million tonnes of grain annually, our beef cattle also graze 70 million hectares of managed pasture as well as another 355 million hectares of native vegetation. They also produce more warming than all our coal fired power stations along with thousands of cases of bowel cancer.

At least one writer at SPA rejects any notion of eating differently. Clearly they are either a climate change sceptic or haven’t done the meat maths – or both. Another SPA writer relates the difficulty of selling the SPA message to the Maasai because they see large families and lots of cattle as part of their culture. An Australian preaching population and cattle control to the Maasai is pretty bloody funny.

If we approach population growth in the right way, it can provide an incentive for us to do things that we should be doing anyway, like reforming our cities. The climate is changing, my generation screwed up and believed the pro-meat myths and anti-nuclear fairy tales and the result has been four decades of cattle and coal. So now we have to prepare for the consequences of our stupidity while trying our best to ameliorate them by getting smarter.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.