As the major parties and the media obsess over the race to surplus, an inconvenient fact is ignored, writes Ian McAuley.

Labor and the Coalition are offering a clear choice of economic plans but the mainstream media are besotted by the sideshow of competing claims by Labor and the Coalition about how their proposals will contribute to the budget deficit in future years.

Normally when someone claims the gift of prophecy our reaction is either to humour the claimant politely, or in extreme cases to prescribe a regime of medication, but somehow we are supposed to take seriously politicians’ competing claims about budget deficits.

It’s a game with little connection to fiscal reality, and even less connection to economic reality.

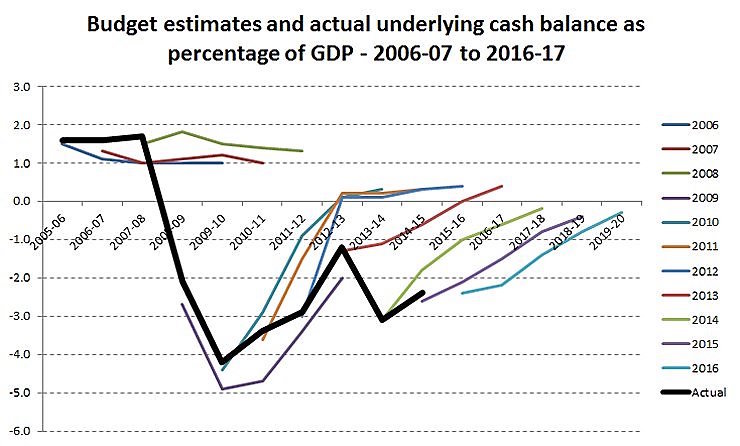

The graph below, derived from a decade of budget papers, shows successive treasurers’ estimates of budget outcomes in coloured lines, and a thick black line of actual outcomes.

Over this period the only treasurer who came within a bull’s roar of getting the surplus/ deficit estimates right was Swan in 2009, when he slightly over-estimated the extent of the likely deficit. Otherwise treasurers have tended to err in the other direction, generally by over-estimating revenue. (Government expenditure is comparatively fixed in the medium term, while revenue, being dependent on corporate and individual incomes, is more volatile.)

The biggest errors were in the budgets leading up to the global financial crisis of 2008. Neither Costello nor Swan foresaw the coming crisis, even though by 2006 it was obvious to economists who could detach themselves from the financial euphoria of the time that a bust was on its way.

Part of the problem is that these forecasts are projections based on estimates (i.e. optimistic guesses) of interrelated core variables – economic growth, unemployment, inflation – published in the budget papers. Although budget papers have a “Statement of risks”, these statements generally confine themselves to minor contingencies – certainly nothing as significant as a global financial crisis or, to take contemporary risks, a collapse in the housing market and a financial crisis in China. And they assume Parliament will pass all budget measures, a heroic assumption in view of the Senate’s opposition to the worst of the Coalition’s expenditure cuts.

Election costings are subject to the same limitations, and in any event they are only statements of intent. Or worse, they are lies designed to get through the election campaign, as Abbott so clearly demonstrated in 2013.

Then, after an election, the incoming government will find some reason to go back on its promises, particularly if there is a change in government. In 2013 the Abbott Government used its handpicked “Commission of Audit” to vilify every aspect of the Gillard-Rudd Government’s economic management, and to set the scene for the brutally destructive 2014 budget. In view of the Abbott-Turnbull Government’s economic mismanagement it would be surprising if an incoming Shorten Government didn’t intend to do something similar.

In the 2016 version of the “your deficit is worse than mine” game, Labor is copping criticism for its proposal to run a higher deficit than the Coalition would in the first few years. But if the Coalition’s deficit is deemed to be responsible, then it’s quite appropriate that a slightly higher deficit is also responsible, because in the six weeks since the budget the headwinds facing the Australian and world economy have become more evident. (As I and many economists have pointed out our headline figures on economic growth mask what is actually an anaemic economic performance). And just in the last few days the World Bank has cut its global growth forecast for this year from 2.9 per cent to 2.4 per cent, with even more dire warnings for commodity exporters.

At the same time as a short-term stimulus is applied there needs to be a plan to bring the budget back to balance, particularly if Australia is to retain its AAA government credit rating.

Although fiscal conservatives say this should be in terms of cutting spending, the reality is that Australia is struggling with one of the developed world’s smallest public sectors.

If we are to develop a proper public-private balance we need more public revenue, and it’s disappointing that Labor is not more assertive in terms of revenue; a carbon tax (extending to automotive fuel), inheritance taxes, a GST rise linked to state revenue (rather than cutting other taxes), and strong action on rorts such as family trusts and fringe benefits. Such taxes could be phased in so as not to deaden the immediate fiscal stimulus while giving assurance that the Australian government has a credible and binding plan to collect revenue and to bring the budget back to balance.

Nevertheless, even Labor’s meek proposals on revenue (and similarly meek proposals on expenditure) are more responsible than the Coalition’s plans for a fiscal giveaway in the form of corporate tax cuts, the cost of which would rise in the outer years. We need a stimulus now, with a plan for withdrawing it down the track, but the Coalition’s proposals are in the opposite direction.

In any event there’s far more to economic policy than fiscal management, and Labor last week laid out its economic principles in its “10 year plan for Australia’s economy” – a document articulating Labor’s economic policy, the central principle being investment – “in schools, TAFE and universities, as well as nation building infrastructure – roads, rail and a first rate National Broadband Network.”

Some have criticised it for being short on detail, but that’s a misunderstanding of its purpose. It’s about principles to guide a Labor government’s economic policies in its budgets and other economic measures. And in any event, it has much more flesh than a three word slogan about “jobs and growth”.

So obsessed have our pundits become with fiscal costings that they cannot recognise a statement of economic principle when it’s put before them. Rather, they do a keyword search for “deficit” (which gets a mention towards the end), and ignore the rest of the document.

It’s hardly surprising that the Murdoch media has distorted Labor’s policies, but it’s unfortunate that the some journalists in the ABC, which has far more credibility, have confused Labor’s policy principles with specific budgetary proposals.

Last Friday for example, following an interview with Andrew Leigh, ABC Breakfast host Fran Kelly joined with Michelle Grattan in their regular review of political issues. The main issue of concern in both sessions was Labor’s proposal to tighten eligibility for family tax benefits. Kelly asserted that Labor was making “backflips on policies that it has held”. In supporting that assertion she said “Jenny Macklin has been assiduous in her protests against the cuts to family tax benefits for years now – I mean her credibility would be shredded if Labor backed those savings”.

Had Kelly and her producers read Labor’s general policy document, or Macklin’s more detailed policy on inequality released earlier this year, they would have realised that there is no contradiction or “backflip” (one of Kelly’s favourite clichés). Ever since the Curtin Government commissioned the White Paper on Full Employment seventy years ago Labor has been committed to the “social wage”, which is about achieving fairness not only through specific welfare transfers such as pensions and unemployment benefits, but also through universal programs in education and health care – and more recently child care. There are sound economic reasons for such payments, and they also have redistributive benefits.

When the Abbott Government proposed cutting family tax benefits Macklin was bound to oppose them, because cash benefits are better than nothing, but Labor has traditionally had a preference for benefits in kind, and that preference has been re-asserted in its policy documents. If Labor can improve the social wage through health and education benefits, it’s quite equitable and in line with Labor tradition to reduce specific cash payments at the same time.

Governments on the “right”, including the Coalition in Australia, tend to prefer redistribution through cash handouts, including measures such tax rebates, on the basis that people should be able to make their own choices. Labor has traditionally preferred to spend on benefits in kind. That preference has to do with community solidarity, and making sure that people who have limited capacity to make wise choices – children in particular – are provided with needed services.

If the media could engage with these basic policy issues, rather than the sideshow of election costings, they could help guide electors through the important choice between the Coalition and Labor policies.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.