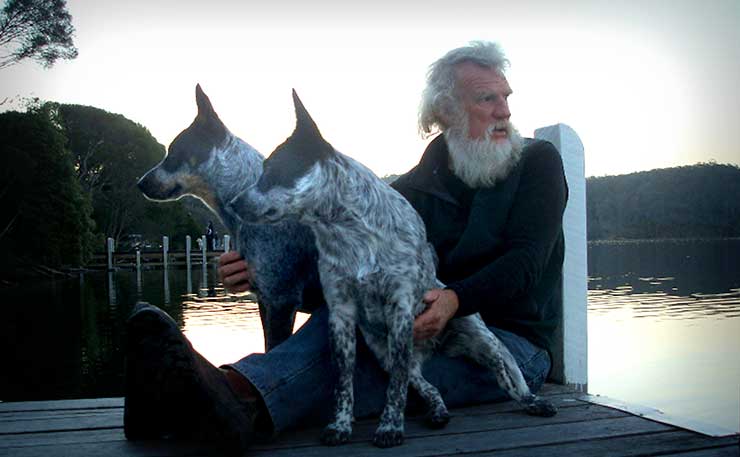

Amy McQuire interviews acclaimed First Nations author Bruce Pascoe, and asks the question why Australia has so readily embraced his book – Dark Emu – and its truths. Does it now mean they must embrace the issue of sovereignty and treaty?

When Bunurong and Yuin man Bruce Pascoe released his acclaimed work Dark Emu, which triumphs Aboriginal agriculture and overturns myths that our people were ‘hunters and gatherers’, he expected backlash. Not only had it taken him a long time to find a publisher (it was rejected by several publishing houses before Aboriginal press Magabala Books picked it up), but it also was written within the enduring memory of the history wars.

“I was expecting there to be a pretty vitriolic campaign against Dark Emu,” he told me on 98.9FM’s Let’s Talk programme this week. “But there wasn’t…. in the media anyway, there doesn’t appear to have been much of a backlash at all.”

In fact, the reception to his book has been the opposite. Just last week, Dark Emu was awarded Book of the Year at the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards, and shared the Indigenous Writers Prize with up and coming Murri writer Ellen van Neervan (for Heat and Light).

It has attracted critical acclaim, and mainstream recognition – despite its core thesis – that Aboriginal nations had, over tens of thousands of years, built up a sophisticated agriculture. They were building ‘dams and wells, planting, irrigating and harvesting seed, preserving the surplus and storing it in houses, sheds or secure vessels… and manipulating the landscape.”

Rather than the myths that our people were hunters and gatherers, Pascoe uncovered this hidden history – including the awe-inspiring fact that we may have been the first people in the world to make bread.

Dark Emu was published after another acclaimed work – The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia – by historian Bill Gammage, which chronicled how Aboriginal people were cultivating the land through a complicated land management system across the breadth of the continent.

Dark Emu was published after another acclaimed work – The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia – by historian Bill Gammage, which chronicled how Aboriginal people were cultivating the land through a complicated land management system across the breadth of the continent.

The two works have been embraced across Aboriginal Australia because they represent the truth about the strength of our peoples, validating what our elders say about the way we managed country.

But I’m perplexed about why it hasn’t provoked the same backlash as the ensuing controversies over issues like the ‘frontier wars’, given that they both fundamentally demolish uncomfortable truths about invasion.

Could Australia finally be growing up? Could this success signal a willingness to break the ‘Great Australian Silence’?

Pascoe believes one of the reasons behind this lack of backlash is it is hard to argue with because of the source of the information – he uses the testimony of explorers themselves, the traditional ‘Australian heroes’. The decision to use explorers, followed criticism from academics, who believed he was lying.

“I was getting rapped over the knuckles by some academics because I had been writing about Aboriginal agriculture and they couldn’t abide that mention. They thought I was lying to the Australian people as they put it, so I thought then that I wasn’t going to convince people by using my own words, and I would have to use an authority that they respected. So that was the explorers and the settlers… you know the ‘heroic’ first settlers.

“I went back and read a lot of those journals … after that rap over the knuckles… I thought I was in school… I went to the first bookshop I could find and I bought Sir Thomas Mitchell’s ‘Journey Into Tropical Australia’ and very soon into that book I read that Mitchell rode through nine miles of stooped grain, that’s grain that has been harvested or stood up on its end… and ready for threshing into grain, and converting that grain into flour.

“Nine miles of it. I put the book down and it thought… nine miles… how could anyone reading this book not find that interesting? And then I read the other explorers’ journals.”

Those testimonies, of yam fields that reached to the horizon and were irrigated, and people in the desert harvesting ancient grains to make sweet and moist cakes, piled up. Example after example of Aboriginal agriculture. The information was hidden in plain sight.

Since then, the criticism has died away. The testimony of explorers is seen as a ‘legitimate’ source.

The judges of the NSW Premier’s Literary Prizes said “Dark Emu injects a profound authenticity into the conversation about how we Australians understand our continent. Pascoe demonstrates with convincing evidence, often from early explorers’ journals, that the Aboriginal peoples lived settled and sophisticated lives here for millennia before Cook.”

The success of Dark Emu has been embraced by even the food industry, and a Pozible campaign for Pascoe and a team of Aboriginal men and women to grow traditional food plants was overwhelmingly successful – with Australians giving $32,800 to fund the project.

But the question still has to be asked, why has Australia so readily embraced Dark Emu, but is still resistant to the brutal truths of this country – the massacres on the frontier?

While it is great that Australia is so ready to engage with the reality that Aboriginal people had a complicated land management system, I feel that their acceptance of this truth at the expense of the dark history of the frontier wars shows they do not fundamentally understand the vital importance of Pascoe’s work – and the far-reaching implications of it.

Pascoe feels that at least part of the reason Australia has embraced his book is because of ‘self-interest’. We are in a desperate stage, searching for solutions, as we head towards climate catastrophe.

“Even though there is this new awareness and interest in Aboriginal agriculture, a lot of it is probably self-interest. But you know, that’s better than nothing. That’s better than ignorance and avoidance and writing a history that demeans our people,” he says.

But this self-interest may overshadow a profound ignorance about what Dark Emu actually means and what a wider awareness and enthusiasm for Aboriginal agriculture could and should lead to – addressing unfinished business.

As Professor of Law Megan Davis explains in the book ‘It’s Our Country: Indigenous Arguments for Meaningful Constitutional Recognition and Reform’, the way the British claimed territory and asserted sovereignty is ‘central’ to where we go next in resolving the unfinished business.

Prof Davis explains: “It mattered whether claiming a territory was done by settlement or whether by conquest and cession, because each had differing implications for the reception or not of British law.

“Settlement occurs when the land is desert and uncultivated and it is inhabited by backward people.

“Conquest means that it is a forcible invasion of occupied land and cession means that there is a treaty over occupied land. In the case of conquest, the laws of people conquered apply until the Crown or other foreign power laws apply, and in regard to cession, a treaty is entered into but the Crown or foreign power abrogates it.”

She writes “When lands are cultivated, then they are gained through conquest or they are ceded by a treaty”. And when lands are conquered or ceded, it still has laws of its own.

“Until the Crown asserts sovereignty and actually changes them ‘the ancient laws of the country remain’.”

This was not fully resolved in the Mabo decision, Prof Davis writes, which resulted in an “uneasy combination of unsettled/settled”. But she writes it’s not the ‘fundamental issue’ – “Sovereignty was not passed from the Aboriginal people through any significant legal act. The British did not ask permission to settle. Aboriginal people did not consent and no-one ceded. This is the source of disquiet. This is the grievance that must be addressed. The further we are from 1788 the less inclined the state will be to address this.”

This, of course, is the source of the controversy. It is the source of the fear that emerges whenever someone brings up the truth of the frontier wars. It is why the frontier wars is so vehemently argued against, and why it is not recognised as wars in our national institutions – like the Australian War Memorial. The frontier wars are not accepted in the national remembering.

But Aboriginal agriculture and land management has been accepted by white Australia, even though it directly addresses the myths about Australia being ‘uncultivated’ land.

The lack of controversy makes me think that Australia is slow to realise this. And it makes me wonder whether the enthusiasm that greets information about Aboriginal agriculture and land management is based on intellectual curiousity, and not a willingness to deliver true justice.

Recognising Aboriginal agriculture and land management not only means recognising the humanity and intelligence of Aboriginal peoples, but that this land was taken by conquest, and sovereignty has never been ceded.

That means if you are enthused about Dark Emu, if you join in the platitudes and accolades, if you celebrate the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards decision to award it “Book of the Year”, you can’t be intolerant to addressing unfinished business – for many Aboriginal people that means mechanisms like a treaty, or at least a conversation around the next step forward.

It also means acknowledging the rights of Aboriginal people to live on their county and continue their culture, and to be supported in that endeavour without persecution.

In the same week I spoke to Mr Pascoe, I also spoke to NSWALC Councillor for the South Coast Danny Chapman, a Walbunga man of the Yuin nation.

In Dark Emu, Pascoe also talks about the way Aboriginal peoples harvested fish, eels and abalone. Meanwhile, on the South Coast of NSW, Aboriginal people are being slapped with harsh fines, and long jail sentences, for exercising this cultural right to fish, against the backdrop of a multi-million dollar abalone industry in their traditional waterways.

Cr Chapman has seen the prosecutions devastate his family and wider community.

“I’ll give you an example – my two sons over the years, have built up fines of around about $10,000 – and the NSW government is waiting to retrieve that money. That has basically ruined their lives. They can’t get a license without paying this money back. They can’t do a number of things, and they’re not the only ones in this boat.

“My brother in law spent 18 months in jail for fishing. The effects of the prosecutions has been quite devastating to our communities and families.

“… Our responsibilities to our country is taken very seriously by our people. But we go down to the ocean and straight away we are under suspicion, we have people hiding in the bushes… they look like commandos… it’s quite extraordinary the lengths the government have gone to stop Aboriginal people from practicing their culture. It’s quite amazing… if you were reading this you’d think it was some kind of fantasy novel… but it’s true.”

So it’s somewhat ironic that the same state should announce Dark Emu as its ‘Book of the Year’, and celebrate it, while its government actively punishes Aboriginal people for continuing the culture the book chronicles – cultural fishing that has stretched back for tens of thousands of years.

This is where I find the success of Dark Emu both exciting, and perplexing. It’s exciting because if Australia begins to recognise what celebrating Aboriginal agriculture means, it could form the foundation of a new conversation around recognising sovereignty, and the grievances at the heart of invasion.

But it is perplexing because of the backlash towards the very idea that Australia was ‘invaded’. Australia needs to move beyond self-interest, and understand what Dark Emu and other works like it mean for our future as a nation.

* New Matilda survives almost entirely on reader subscriptions. If this sort of writing is something you value, please consider subscribing today. Subs start from as little as $6 per month – click here for details.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.