While Burma makes gains, the two nations, long rivals, are heading in the wrong direction, writes Alan Baxter.

The governments of Thailand and Cambodia have historically held an uneasy relationship to say the least. Recently the two countries came to blows over the 11th Century temple of Preah Vihear (the Khmer name for the temple but also known as Prasat Phra Wihan in Thai) located in a disputed border region. They set about provoking each other with minor intrusions and more serious bloody skirmishes between soldiers.

Thailand, after an unfavourable International Court of Justice decision awarding the temple to Cambodia, quickly erected a large mock model of the temple quite near the original to appease the ultra-nationalist Thais upset about the decision. It has yet to be opened and may face the demolition ball before any tourist steps foot inside but remains a good example of the simmering tensions and animosity between the countries.

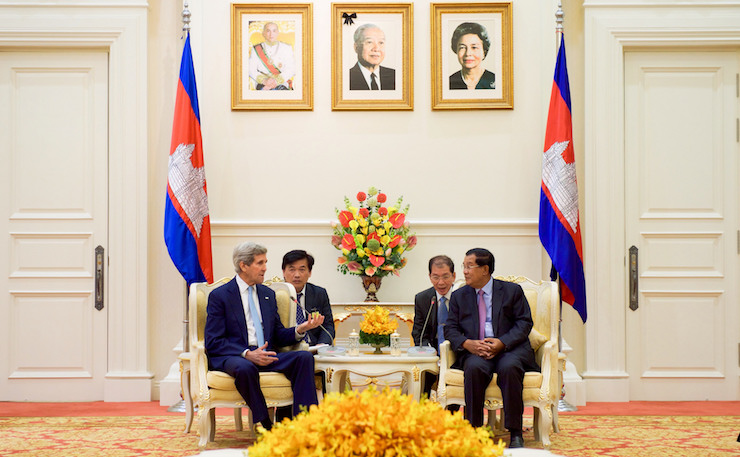

Yet since the military coup d’état in Thailand in May 2014, both governments seem to be reading from the same book when it comes to consolidating power and quashing dissent. In late 2014 Cambodian Prime Minister of 18 years Hun Sen and the former Thai military General turned junta leader, Prayut Chan-o-cha met on the sidelines of a regional summit. This encounter was followed by an official visit to Thailand by Hun Sen at the end of 2015, his first in 12 years. It may be a coincidence but since these encounters both states have been in furious agreement about the tactics needed to maintain power and control in the face of growing public backlash, both on the streets and at the ballot box.

Both leaders are highly sensitive, verging on paranoid, about political dissent and are swift to crack down on protestors. Neither seem to care one bit about domestic or international criticism condemning their stifling of dissent.

Cambodia is well known for its poor human rights record, brutal suppression of human rights activists, systemic corruption (ranking highly on the corruption index) and the erasure of the separation of powers between the Prime Minister’s office and that of the judiciary. Thailand, having just experienced its 19th coup d’état since 1932, is hardly any better, as exemplified by the slave conditions in the southern Thai fishing industry and the mafia like corruption endemic the industry that led the senior military official investigating human trafficking to flee the country and seek asylum in Australia for fear of retribution.

The mistake the official made was that he surprised everyone and actually carried out the job with which he was tasked. The official named senior military figures as complicit in human trafficking and by so doing effectively signed his own death warrant. He knew the system well enough to get out before it was too late.

A quick survey of recent suppressions of rights and freedoms offers a worrying, and at times, bizarre insight into these countries’ increasingly dystopian socio-political conditions. What emerges is the power of symbolism, in that it is as much a propaganda tool for the governments as it is a source of extraordinary paranoia, and both leaders are quick to quash any symbol deemed rebellious.

In Thailand it is now illegal to; throw water from a red bowl during the water festival (the red bowl is a symbol of the former Prime Minister and “red shirt” leader, Thaksin Shinawatra, now officially persona non-grata – the junta has written him out of the school history books); hold a three finger salute (a symbol drawn from the film Hunger Games which will land you in detention for what the junta coined “attitude readjustment”); or to hold an A4 piece of paper in the air which says “Coup makers fear A4 paper, A4 paper is coming to you now” (the perpetrator of this heinous crime received six months hard labour and a ten thousand baht (AUD 350) fine).

As strange as these cases sound, they are indicative of a serious deterioration in respect for human rights and basic freedoms and the overreach of power in the hands of an authoritarian leader.

Meanwhile in Cambodia, while slightly less bizarre but equally brazen, the “shirt colour” politics that consumes Thailand’s political landscape has found its way to the country. The government recently arrested and intimidated protestors wearing black shirts as it was deemed an “urban rebellion”. Hun Sen is eyeing the tactics of his military friend across the border as he desperately tries to stamp out Thailand’s colour coded politics used so successfully as an electoral tool during the Thaksin era. Back in Phnom Penh, the black shirts were worn by protestors at a “Black Monday” street protest in support of detained human rights defenders, involved in what can only be described as a political soap opera. The activists are charged with corruption for offering legal support to the alleged mistress of the current and widely popular CNRP deputy opposition leader Kem Sokha. This case has all the hallmarks of a political stitch-up by Hun Sen to destroy any legitimate opposition in the lead up to the provincial elections in 2017 and presidential elections in 2018. If he succeeds, it is possible that the opposition CNRP will be so damaged that Hun Sen will be able to install a puppet leader, especially while the CNRP leader, Sam Rainsy, remains in self-imposed exile with numerous defamation charges hanging over his head and the prospect of judgement by a politically corrupted judiciary.

Add to that a splash of political opportunism by Hun Sen, in seizing a chance to cripple a high profile human rights and democracy civil society organisation at the same time.

Both the regimes have introduced laws to curb freedom of expression, press freedoms and cyber freedoms. There is no doubt that social media is being heavily monitored in both countries and bloggers as well as citizens exchanging private messages through social media platforms have been arrested. The eyes of the state are firmly fixed inside its citizen’s computers.

In Thailand, the use of lèse majesté, a draconian law that purports to protect the King, is routinely and increasingly used to punish political opponents of the junta with sentences of up to 30 years imprisonment. Thailand’s draft constitution is currently being prepared for a public referendum. This will be the 21st such constitution since 1932 when Thailand transitioned from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional democracy (albeit in the broadest sense of the term). Despite the constitution being the highest law in the land for its citizens, open debate, criticism or discourse in the lead up to the vote in August has been banned, punishable by 10-years imprisonment.

These attacks may well amount to an irreversible decline in freedoms and democracy under both administrations, perhaps for decades to come. While their Burmese neighbours to the west are trying to transition from the dark and brutal past, hoping to leave behind the years of repressive rule under the notorious SLORC junta, Thailand and Cambodia are regressing, and could certainly be considered far less democratic than Burma is now.

It seems that at the Prayut and Hun Sen Book Club, George Orwell’s 1984 is the prescribed reading.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.