Australia’s nuclear medicine industry provides a crucial service to the nation, writes Dr Geoff Currie.

I refer to Nuclear Waste in Australia: A Few Home Truths, New Matilda, 7 March 2016.

Dr Beavis has a strong and ideological position against the nuclear industry, and that is absolutely her right, but I write to put the facts on the record and refute some ‘truths’ put forward recently.

Firstly, on where and how nuclear medicine is used.

If you have had bone, heart disease, liver, renal disease or cancer, then the chances are that you have had a nuclear medicine dose from Australia’s nuclear reactor.

Secondly, on how often it is used.

If anything, the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) is actually underestimating it when they say that one in two Australians will, on average, have a nuclear medicine dose during their lifetime.

Based on my numbers, it is more likely that the case is that on average, every Australian would have two or more doses during their lifetime.

Between Medicare and the state hospital system, around five per cent or more people will, on average, have a nuclear medicine procedure per year – half of the population every 10 years.

The Medicare figures referenced by Dr Beavis are not accurate because they don’t account for the nuclear medicine used on inpatients across the entire network of state public hospitals, where the biggest nuclear medicine departments in the country are based.

Thirdly, on the amount of Australia’s nuclear waste that can be attributed to nuclear medicine: I will let the facts speak for themselves.

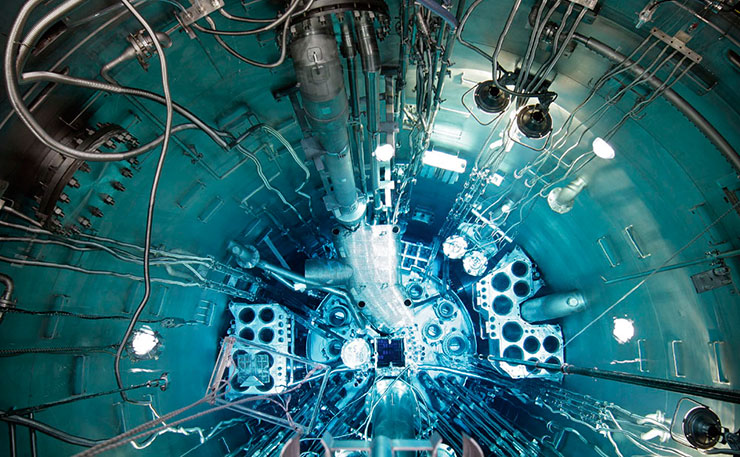

The reactor at Lucas Heights is used for nuclear medicine production, and accounts for most of Australia’s current waste production. Some 75 per cent of the low level and 98 per cent of the intermediate level waste is linked to nuclear medicine.

Dr Beavis and other campaigners are correct that nuclear medicine itself is short-lived, and that it therefore does not contribute to the wastes that need to be managed safely over the longer term. But that doesn’t account for production of the nuclear medicine.

Just like with the food and resources cycles, the end product used by the consumer is not the critical waste point, it is the production process.

If you don’t have production, you don’t have medicine.

Fourthly, on the argument that little has been said about ANSTO’s plans to ramp up nuclear medicine production, that’s just not correct.

There have been huge amounts of information on Australia’s $168.8 million factory at Sydney’s Lucas Heights that will enable international supply of around 10 million nuclear medicine doses a year.

That information outlines two components.

The first is a new medical factory with significant production capacity and state-of-the-art technology, which I have seen under construction, and it is shaping up to be an incredible facility.

The second is a waste management facility that will use Synroc technology to lock up the by-products, and reduce their volume by up to 95 per cent compared to methods such as cementation.

So in the end the project will aim to both produce more medicine and less volumes of waste than is currently the case.

There has been freely available public information on this initiative, because it is global leadership that Australians should be proud of.

Fifthly, on whether we should be exporting this medicine, let me say this.

Australia and our health community are global citizens. If a cure for something like HIV was developed in the USA, we would expect them to share it with us.

In Australia our nuclear medicine production techniques are the envy of the world, with low enriched uranium fuel and target plates – the only such facility on Earth.

We have an obligation to use our technology for good.

There is world demand for 40 million doses a year of nuclear medicine, yet the reactors that make about 70 per cent of this are ageing and due to shut down.

It is good global citizenship to share our expertise, particularly when the likely alternative would be someone else stepping up, but producing the medicine with high-enriched uranium technology, which works against Australia’s non-proliferation goals.

Sixthly, on the argument that we should follow Canada, and try making nuclear medicines in cyclotrons – the inconvenient truth, as I have repeatedly said, is that they can’t replace a reactor.

Given that this false argument keeps coming up, let me explain this in depth, and put this incorrect argument to bed once and for all.

While some would argue that Australia is the global expert, Canada is certainly one of several countries that have a strong reputation in nuclear science.

Canada’s first option to replace their ageing medicine-producing reactors was to build new ones, and they invested hundreds of millions of dollars in that.

Unfortunately for them, a series of engineering and regulatory failures saw the plans mothballed, so trying to make nuclear medicine in cyclotrons is a forced plan B and, as predicted by the OECD report referenced by Dr Beavis, it’s not working.

Cyclotrons cannot effectively produce the workhorse of nuclear medicine, technetium-99m, which accounts for 75-80 per cent of global nuclear medicine procedures.

The yields are lower, costs higher, reliability more variable and service delivery inferior.

Yes they have indeed conducted successful experiments – and let us take a moment to look at the results.

After a 6 hour bombardment of a very expensive target in a very expensive cyclotron, at best they were able to produce, purify and deliver, enough nuclear medicine for three teaching hospitals.

That means there would not be enough for any emergency on-call solution, and nowhere near enough to supply the 250 hospitals and nuclear medicine centres that we have in Australia alone.

I have seen the proposals in the Canadian government report that Dr Beavis referenced, including the part where it says that even if they were to one day use this technology to produce enough nuclear medicine for a domestic supply, they still need the option of a back-up international supply.

And I have seen the 2010 OECD report that was also referenced, and note that it was based on estimates, predictions and assumptions that have since been proven false, and even on those optimistic estimates, the report still said cyclotrons would be a more expensive alternative.

Cyclotrons just cannot replace the reactor.

Let me conclude by saying this.

Dr Beavis inferred that relying on our nuclear reactor for nuclear medicine instead of cyclotrons, is the equivalent to continuing to rely on coal for energy instead of renewables.

Leaving aside that Australia has a 21st century nuclear reactor, and also that cyclotrons can’t produce the medicine needed in terms of quality and quantity, let’s follow the analogy.

In terms of quantity: if we turned off every coal-fired power station right now, would we have enough renewable energy to power 100% of Australia? Not even close.

What about in five years? Or ten? Closer, but still likely no. And at what cost?

At the moment, reliable renewable energy solutions are largely for the rich, and arguably out of the reach of much of Australia, and certainly most of the world.

Basically if we turned off the coal fired power stations right now, much of Australia, and most of the world, would be left in the dark, with the poorest communities suffering the most.

The same applies for nuclear medicine.

If cyclotrons worked, and we moved to that model, you would instantly and dramatically increase costs and decrease availability, and force an economic divide in nuclear medicine supply between the people and countries who can afford it, and those who cannot.

To give an indication of cost to put these technologies in place, a European report indicates each hospital (ignoring private clinics) would need their own cyclotron on site.

Given that Australia alone has 250 hospitals and nuclear medicine centres that receive nuclear medicine, first you would have the multi-billion dollar cost of building hundreds of cyclotrons.

Then you would also need to buy chemistry laboratory equipment for each site.

Then recruit operational staff and expertise for each site.

Then come up with a waste management solution for each site.

Then manage regulatory approvals and compliance for each site.

Then build and administer a contingency for service and breakdown.

The costs of this model would be astronomical compared to the centralised, reactor-based model that we have in place right now.

The technologies and economies of scale might change one day, but we are talking about nuclear medicine production techniques right now, and waste being produced right now, that needs a solution right now.

I am one of Australia’s lead researchers in the field of producing nuclear medicines with alternative technologies to reactors – and I can tell you that the alternatives currently and in the foreseeable future, are not capable of replacing reactors.

I am also telling you that we have already had many, many years of debate and inquiry into everything nuclear, and we don’t need yet another one – we need a solution.

The solution for Australia’s legacy waste and future waste is to bring the material that is currently held in more than 100 hospitals, universities, ANSTO and the CSIRO, into one safe, single location.

The solution is the National Radioactive Waste Management Facility, in line with what the government has proposed.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.