Robert De Niro is in trouble over withdrawing a film about vaccination from New York’s Tribeca Film Festival; a festival he and a couple of others founded in 2002.

The film’s director is disbarred medico Andrew Wakefield. How is it that somebody who has defrauded a major medical journal can make a film? All it takes is an acausalate source of funds.

What’s that word? Acausalate? It’s a new word … but sorely needed.

Literacy has always been a big deal and numeracy long ago moved from being a bit-player to a co-star in the essential skills Oscars. But where is causalacy? Why don’t we have a word for people with a solid grasp of causation and the ability to differentiate between it and its frequently confused doppelganger; correlation? Causalacy obviously goes with causalate, and its opposite is acausalate.

Unfortunately, the causalate club is far more exclusive than the literate and numerate clubs; thinking you’re a member is a sure sign that you aren’t. Causality confusion can hit any of us without obvious symptoms.

If you are thinking of applying for the club, then try the following as a little self-test.

Suppose big pharma develops a drug. It passes all the safety tests and they are ready to see if it actually works! So they gather a group of 350 men and 350 women with a deadly disease; 350 take the drug and 350 don’t.

Of those who take the drug, 78 per cent recover and the rest die. Of those who don’t, 83 per cent recover and the rest die. So the chances of recovery are better if you don’t take the drug. Okay, so stop the production lines and sack the researchers.

But perhaps there’s a possibility you may not have considered.

Suppose there is a causal interaction between the drug and the sex of people taking it. Here’s what could have happened. Keep in mind, the numbers above still apply, but among the men taking the drug, 93 per cent recovered and among the women taking the drug the recovery rate was also good at 73 per cent. So the drug is good for men and good for women… so how come it wasn’t good overall?

Here’s one possibility. Suppose the drug made men impotent; so most refused to take it. After all, men have a long history of preferring death to dishonour. So only 87 of 350 men took the drug while 263 women took it.

This example is rather artificial because the causal features have been deliberately made obvious. But what if the drug interacted with some unknown genetic or lifestyle attribute of the people being tested?

This example is actually decades old and even has a name; Simpson’s paradox. What’s far newer, and very much at the bleeding edge of science, is the deep realisation that we never really understand numbers without understanding the processes which produce them.

Which brings me back to De Niro and vaccinations and the acausalacy that the anti-vaccination movement relies on to attract followers. When a child develops a dread disease in the first 12 months of life, it will always be within months and sometimes within weeks, days or hours of a vaccination and the urge to connect one with the other will be extreme; we are all prone to acausalacy at such times. It’s in our genes.

Put lithium chloride in a piece of lamb meat and feed it to a wolf and they’ll throw up. They will subsequently think lamb meat is the cause and even the smell of lambs can then make them vomit; and leave lambs alone.

Similarly, I had food poisoning one evening after eating lunch at an Adelaide cafe. Despite knowing that food poisoning can take 3 days or longer to develop, and despite there being at least half a dozen plausible suspects, I couldn’t walk past that cafe without feeling physically nauseous for over 12 months.

The urge to ascribe an effect to something close at hand isn’t a failing of the feeble minded; it’s an incredibly useful and highly evolved skill. But it can cause serious blunders; as it does with anti-vaxxers.

Vaccine makers actually know their job. They know a considerable amount about how vaccines work and are also acutely aware of the responsibilities of preparing any substance for use in infants.

They are constantly monitoring for real adverse reaction patterns. Such patterns do occur from time to time and vaccines are withdrawn.

But the mathematics and science behind differentiating a coincidence from a cause is hard. It’s much easier to throw together junky correlational studies and point the figure at vaccines, or sugar, or Fukushima radiation, or whatever your favourite fear is.

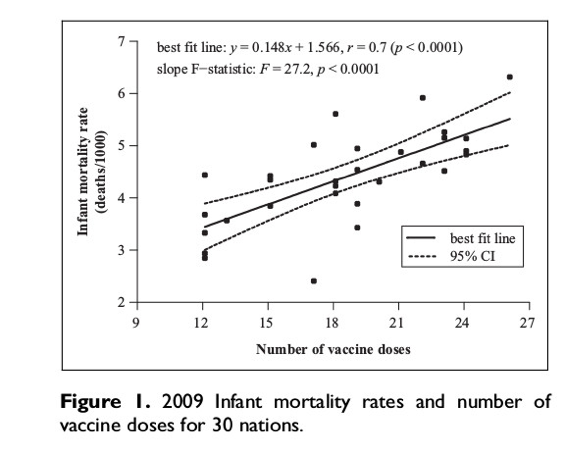

Here’s an example of a paper cited on the Australian Vaccination-skeptics Network website. The image is superficially compelling and worth discussing at length.

Here’s what the self proclaimed skeptics say about the graph.

“A study by Miller and Goldman demonstrates in striking visual form that the number of infants dying each year increases in proportion to the number of doses of vaccine routinely injected into them [A].”

Let’s think about the processes producing the data and ask the kind of questions that a real skeptic might ask.

First some background: The study looked up infant mortality rates (IMR) in various countries… this is the percentage of children born alive but who die before they are 12 months old.

It then looked at the number of doses of vaccine scheduled during the first 12 months in each country and plotted a regression line.

Here are some pretty obvious questions:

- How many infants die, for example, in accidents during the first 12 months? Any child who died from something clearly unrelated to vaccinations should have been removed. In the US, for example, the 10 leading causes of infant mortality are, in order: congenital malformations, low birth weight, birth complications, SIDS, accidents, other complications, bacterial sepsis, neonatal respiratory distress, diseases of the circulatory system, neonatal hemorrhage. Between them these 10 account for some 70 per cent of infant mortality; and has nothing to do with vaccinations. What about SIDS? The evidence says no but the rumours will continue as long as any of SIDS’ causes remain a mystery. In any event, SIDS in the US is trending down and this is tough to reconcile with vaccines having any kind of role. So, for the US, the study should have plotted vaccination doses against, at most, the remaining 30 per cent. It’s similar with other countries, but the numbers may well be different.

- Some vaccination doses are generally due at around 12 months… but were counted in the study. But what if a child dies earlier than 12 months of age? Most who die before 12 months will die before these last vaccinations. So the plotted correlation is actually mainly irrelevant deaths and vaccine doses, some of which weren’t even received.

- Vaccination rates are rarely 100 per cent, so again, did they remove the infants who died without being vaccinated at all? No.

- Does the study do any of the normal things that good studies of this kind do? Meaning to correct for other things that might raise IMR rates, like poverty, poor water supply quality and nutritional factors. Statisticians call these confounders and they are a devil of a problem to deal with. This study doesn’t even try.

Which brings us to an even bigger problem.

Why are there so few dots on the graph? There is one dot per country and there’s a lot of countries in the world… where are the missing countries and why are they missing? There are 63 countries listed in what is called the higher-income-group based on Gross National Income (GNI) per capita rankings, so why pick just 34?

You might expect poor countries to have a high IMR for other reasons, so it would be reasonable to pick only countries with a GNI above some chosen figure.

The poorest country on the list is Cuba. So there really needs to be an argument for excluding any country richer than Cuba. There are 96 countries richer than Cuba, so why were they omitted?

You can see how critical it is to actually think about causes when you design studies like this.

If the association as shown in the paper really is causal, as those citing the study clearly think, then you should see a low IMR for countries with low vaccination dose numbers. Is this true?

Grenada, a country wealthier than Cuba, has a vaccination schedule of some 15 vaccine doses in the first 12 months, but her IMR was over 10 at the time used by this study; and is still high.

Similarly, Venezuala is also richer than Cuba, but also gives infants fewer vaccine doses than the US, 18 compared to 26, but had an IMR of 16. Other countries which would muck up the regression are Croatia, Oman, Peru and Uruguay with IMRs of 5.7, 9.7, 18.6, 13.4 and vaccine doses of 16, 16, 18, 16 respectively. And that’s just a few that I bothered to check.

I could have checked all of the 96 missing from the chosen 34, but a dumb method is still dumb even if you bother to do it a little more thoroughly.

The Australian Vaccination Network recently renamed itself the Australian Vaccination-Skeptics Network. Their complete gullibility in praising this study shows that they still haven’t got a name which describes themselves.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.