Malcolm Turnbull has put the ABCC front and centre. Thom Mitchell outlines what you need to know about the Commission’s history, the government’s case, and why the Law Council and the CFMEU find themselves on the same side of the debate.

It’s looking increasingly likely that the government will bring on a July 2 double-dissolution election, on the basis the Senate is refusing to back its legislation reviving the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC).

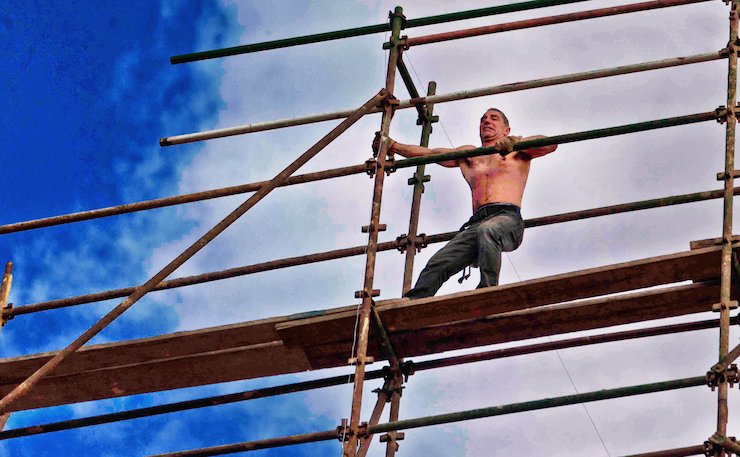

The legislation is a reincarnation of a similar body which the Howard Government established in 2005. It’s essentially a tough cop on the building and construction industry beat, which the government maintains is plagued by “militarism and illegality”.

The government’s response, though, has been slammed by the Australian Law Council, Labor, the Greens, and the union movement. Collectively, they argue the government is essentially engaged in union-busting which would strip away workers’ civil rights merely because of the industry they work in.

The Australian Building and Construction Commission legislation is pretty intense: It would reverse the onus of proof, remove the right to silence, and allow officials of the ABCC to enter premises without a warrant and demand to know names and addresses.

The ABCC Bill has already been knocked back in the Senate once, in August last year, with crossbencher Senators Jacqui Lambie, Glenn Lazarus, and Ricky Muir voting against it. In order to get the legislation passed when Parliament returns for a special sitting in April, at least two of those Senators would have to change their minds.

Otherwise, it seems, the government will seek a mandate from the electorate – and a less ‘feral’ Senate – by taking the extraordinary step of calling a double-dissolution.

That being the case, it’s worth taking a close look at what the Australian Building and Construction Commission is, whether it’s necessary, and why it’s attracted such broad-scale opposition.

The Government’s Case And The Numbers Problem

If reestablished, the ABCC would be more or less the same as its Howard-era antecedent, which came about as a response to the Cole Royal Commission’s damning 2003 report into the building and construction industry.

The argument the government is now trying to make, more than ten years on, is that the issues identified in the Cole Royal Commission persist, and that the ABCC had proved to be an effective watch-dog before Labor scrapped it.

According to the bill’s explanatory memorandum: “Its most significant provisions…were directed at the unique nature of the building industry, and addressed specific inappropriate and unlawful behaviour which the Royal Commission found was prevalent in the building industry.”

In a Senate Committee report tabled earlier this month, the government cited the Construction Forestry Mining and Energy Union’s (CFMEU) own submission as proof that the industry continues to represent a “singular problem” which demands its own watchdog.

According to the CFMEU, more than 500 workers are being, or have been, prosecuted by Labor’s Fair Work Building Commission, which replaced the old ABCC in 2012. The CFMEU has over 100,000 members and 400 union officials, so it’s still a very small proportion of the industry.

On top of that, according to the union’s National Secretary Dave Noonan, many of those 500 prosecutions have been launched “for things like going to a rally”.

The government also argues that “While the ABCC existed, the performance of the building and construction sector improved”. In the explanatory memorandum of ABCC mark two, the government argues that “industry productivity improved” between 2005 and 2012 and “there was a significant reduction in days lost through industrial action”. Both claims are disputed.

The government is relying on old modelling – which Labor and the unions argue is shonky – in staking its claim that the ABCC will lead to higher productivity. In a Senate Committee report of December 2013, the government relied on modelling commissioned by the Master Builders Association to make the claim that “productivity grew by more than 9 per cent” under the ABCC.

Labor and the union movement, however, dismiss this “flawed and discredited” analysis.

“Relying on a continuing modelling estimate and representing this as evidence as demonstrating the ‘successes’ of the ABCC is neither accurate nor appropriate. The credibility of the 2007 [Independent Economics] report has been demolished by the respected academic Professor David Peetz,” Labor said in one of a number of dissenting reports that have accumulated over the years.

“Further, the Hon. Murray Wilcox QC described the 2007 report as “deeply flawed” and concluded that ‘it ought to be totally disregarded.’ It is from this discredited report that the 9.4 per cent figure of lost productivity is derived [and] it should not be relied upon…”

So in reality there’s no solid data on what the productivity impact of the ABCC was.

The government has also claimed that there has been an escalation in “unlawful industrial action” since the ABCC was repealed, including “bans on working, employees failing to attend work and employers locking out employees.”

Again relying on employer association-commissioned modelling, the government argues that “there has been a threefold increase in working days lost to industrial disputes since the ABCC was abolished”.

“Independent Economics reports that this has increased from 24,000 days in the 2011-2012 financial year to an estimated 89,000 days in 2012-2013,” the government suggests.

Obviously, whether we need to bring back the ABCC depends who you ask in a not-dissimilar way to the recent debate over the Royal Commission Into Trade Unions. The government says the construction industry is riven with corruption and lawlessness, and tackling that is inherently in the interests of workers.

The last main point in the government’s case for the ABCC is that “the objects of the [old ABCC]Act were furthered by the inclusion of appropriate penalties and the establishment of an effective regulator which had a full suite of powers available to it”.

And when they say a “full suite,” they really mean it.

What The ABCC Means For Civil Liberties

If the government succeeds in reestablishing the ABCC it would be granted extraordinary powers, which Labor asserts are even greater than those enjoyed by state and Federal Police, or even the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO).

If exhumed, the ABCC could:

- Compel workers to give evidence and be interviewed, while stripping them of their right to silence and representation from a lawyer of their choosing.

- Force workers to produce documents or information relevant to an investigation.

- Enter premisses without a warrant, and demand people provide their name and address.

- Exercise these powers retrospectively in many cases.

The Bill would also pave the way for extraordinary fines, which could be higher simply because they were related to the building and construction industry. In other words, a worker or union official could commit an offence covered by the Fair Work Act, but be fined more simply because of the industry they work in.

The onus of proof would also be reversed by several aspects of the legislation, mostly in relation to industrial actions, with responsibility transferred to workers who’d have to show they acted within the law. New civil penalties would also be introduced for unlawful picketing, and other penalties for unlawful industrial action would be brought back.

It’s a grab-bag of powers that any law-enforcement agencies would envy, and one which has led the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Human Rights to express concern.

The Law Council of Australia has backed those human rights concerns, and strongly recommended against the bill. In a submission to government in February this year the Council states:

A number of features of the Bill are contrary to rule of law principles and traditional common law rights and privileges such as those relating to the burden of proof, the privilege against self incrimination, the right to silence, freedom from retrospective laws and the delegation of law making power to the executive.

It is also unclear as to whether aspects of the Bill which infringe upon rights and freedoms are a necessary and proportionate response to allegations of corruption and illegal activity within the building and construction industry.

The Law Council has also expressed concern that the Employment Minister could fire the Commissioner without providing any reasons, and agreed with the Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights that the Commissioner’s power to delegate responsibility down to “a person” of their choosing are overly broad.

There is also a more fundamental problem, too, according to Labor. While the government’s rhetoric is focused squarely on allegations of corruption and illegal activity, the watchdog would have “no power in criminal matters” and so it is “deliberately misleading” to suggest it would work to alleviate corruption.

In spite of these widespread criticisms, the government argues the bill is a “necessary and proportionate response to increased militarism and illegality in the construction and building industry”.

It’s likely that question could now fall to voters to decide, if the government fails to shift crossbench Senators in April and goes to a double dissolution election seeking a mandate for the reform.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.