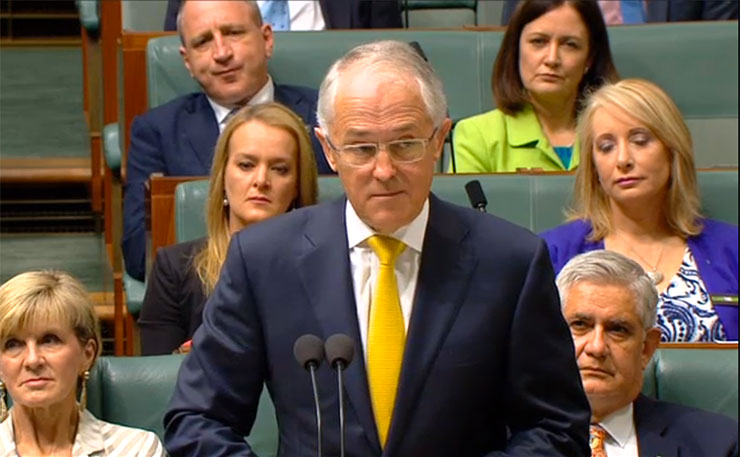

The Liberal Party has been celebrating the Howard years this week, a time of stability and control for conservatives. But it’s the previous Labor government which increasingly bears comparisons to Malcolm Turnbull’s team, writes Ben Eltham.

The Guardian’s Gabrielle Chan published a lovely colour piece on the website this morning, describing the events last night at Parliament House.

Malcolm Turnbull arrived and greeted Howard. A photo was called for. Howard – ever the uncle – suggested bringing Tony Abbott into the picture. “That’s not going to happen,” said someone from behind. Abbott lurked. Somewhere, a glass broke …

Turnbull and Abbott sat within range but there was no interaction after the first handshake. No eye contact. It was like having the divorced parents at the same wedding table.

The occasion was the 20th anniversary of John Howard’s 1996 election victory, a moment that now seems a very long time ago.

It’s worth reflecting for a moment on that pivotal event. It ended thirteen years of Labor government under Bob Hawke and Paul Keating, and ushered in eleven years of Coalition government under John Howard.

Australia in 2007 was quite different to the Australia of 1996. As Norman Abjorensen wrote in a fine essay on Tuesday, Howard “was one of very few holders of that office who could be classed as transformational.” Howard remade Australia, and the nation we live in now is only beginning to acquire the historical perspective required to understand how.

“The times will suit me,” Howard famously predicted in 1986, and for many a sun-drenched year of the early 2000s, that looked to be the case. Howard’s unique blend of social conservatism, economic liberalism and political savvy seemed perfectly adapted to a prosperous and hedonistic Australia enjoying soaring economic growth and ever-rising house prices.

Howard’s remarkable gifts as a politician were honed over forty years in politics, essentially the only profession he ever seriously considered. Perhaps his most underrated qualities were those of patience and caution. Whatever the guff often spouted about his supposedly uncanny ability to summon the zeitgeist of “middle Australia”, Howard was an unusually clever tactician. His favourite tactic, the wedge, was to take a position just to the right of the political centre, and wait for his opponents to stumble. As the years lengthened and the election victories mounted, his prowess came to seem almost supernatural. Only hubris brought him down: the fatal miscalculation of WorkChoices.

How distant those happier times must seem to the contemporary Liberal Party under Malcolm Turnbull.

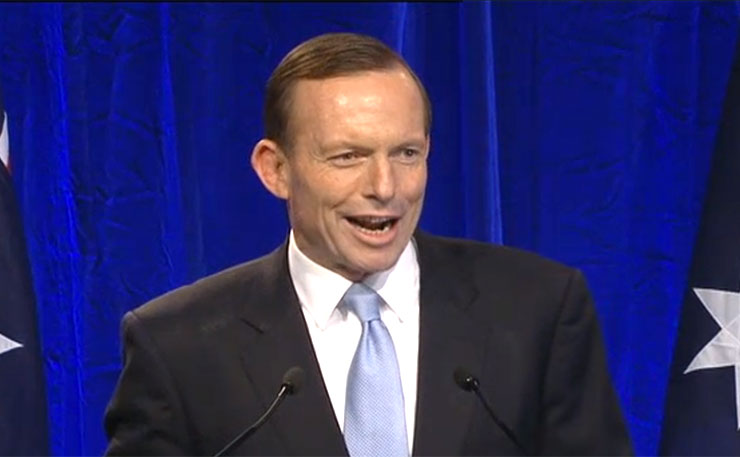

Despite regaining office under Tony Abbott in 2013, the party was forced to dump him after just 23 chaotic and unpopular months. The Liberal Party of 2016 is led by a man many in the party consider to be an imposter – perhaps even a traitor – to their cause.

The Liberal Party is today riven with factional tensions. The new leader, superficially so attractive, has so far proved incapable of uniting his party or stamping his authority on the office. The old leader lurks in the background, stirring up trouble, subtly agitating against the man who replaced him.

All in all, the best comparison is not with the sunny uplands of Howard’s long reign, but the violent instability of the Rudd-Gillard years.

The continuity with Labor’s devastating internal civil war must be troubling many in the parliamentary Liberal Party, not least the leader himself. When Abbott left the prime ministership, he promised not to leak or background against the man that had vanquished him. “There will be no wrecking, no undermining and no sniping,” the outgoing prime minister promised. “I’ve never leaked or backgrounded against anyone and I certainly won’t start now.”

Like so many of Abbott’s other promises, this was soon broken, and never more spectacularly than this week, when someone with intimate knowledge of the highest levels of Australian defence planning leaked sensitive information about Australia’s plans for new submarines to The Australian’s Greg Sheridan. An incensed government immediately called in the Australian Federal Police.

Both Abbott and Sheridan maintain that the leak is not from the former prime minister, but it must have come from someone with very high security clearance.

The fact that Sheridan quoted Abbott in his story and the well-known friendship between the two men adds grist to the rumour mill. Fairfax’s defence correspondent David Wroe wrote today that “it was a breathtaking breach of basic responsibility for a former prime minister and member of the national security committee of cabinet.”

This is not the first leak against Turnbull from the Abbott camp. A low-level campaign of destabilisation began just days after he left the Prime Minister’s suite. Abbott loyalists like Kevin Andrews and Eric Abetz have also been unhelpful, to say the least, while the religious right of the party has gone on a rampage over the Safe Schools issue.

As a result, Turnbull now faces the spectre of a full-scale campaign of destabilisation from Abbott and his forces, just months after taking office. The parallels to the Rudd-Gillard years couldn’t be clearer.

Labor’s civil war showed just how devastating internal disunity can be for a ruling party. By the beginning of 2013, the atmosphere inside the parliamentary Labor Party was so poisonous that almost every policy issue was refracted through the lens of leadership tensions. After a bizarre intervention by Labor veteran Simon Crean in March of 2013, Gillard was forced to sack all the Rudd loyalists in her cabinet. The party spent the rest of its term in government tearing itself apart.

It couldn’t get that bad for the Liberal Party, could it? Well yes, it could.

As long as Tony Abbott remains in the Parliament, he will remain a destabilising force. Opposing is his favourite position.

Everything we know about Abbott tells us that he will never forgive, nor forget. The man who sacrificed everything to get to the top job will forever harbour grandiose visions of revenge. And for ideological and factional reasons, the right of the party will never truly accept Turnbull as prime minister. There was an ominous taste of this just weeks after the Turnbull ascension, when a New South Wales Liberal Party conference audience jeered Turnbull for claiming “we are not run by factions.”

In the end, only a convincing victory at the coming federal election can cement Turnbull’s place in the party. But with the polls narrowing, and Turnbull’s honeymoon starting to fade, that victory is no longer assured. The stumbles of the past few weeks will embolden Abbott and his allies to keep wrecking. They can hardly have forgotten Labor’s disastrous 2010 election campaign, when damaging leaks against Gillard from Rudd backers almost handed Abbott victory.

So the factional instability in the Liberal Party will go on. No wonder Nikki Savva and many others are urging Turnbull to call an election immediately.

In volatile moments, leaders can sometimes panic when discretion is better advised. Would an early election really be in the government’s best interests? Malcolm Turnbull might be well advised to think about what John Howard would have done in these circumstances. It will take plenty of Howardian patience and persistence to see the government through some testing times.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.