Cory Bernardi is not just out of step with his ‘fear the queer’ campaign. He’s also confused about basic political theory, writes Howard Prosser.

As a social conservative, Federal Senator Cory Bernardi’s ruthless attack on an important anti-bullying program is understandable. Anything that might be a ‘little bit gay’ is, under this logic, distasteful and thus deserves marginalisation and intimidation.

But Bernardi’s accusations against the Safe School Coalition is a gross misrepresentation of another social minority without a significant voice in today’s Australia: Marxist cultural relativists.

This group has a right to be outraged. Or it would do, if it was a group that actually existed.

Bernardi’s comments reveal his poor grasp of how social theory has transformed in the last 20 years. Today’s theoretical affinities are far less rigid than in the past: tiresome and predictable nit-picking between Marxist factions was the stuff of the 1970s and 1980s.

Even postmodernist relativism was wearing thin by the century’s end as scholars and activists sought something more concrete on which to hang their commitments.

Few academics these days identify as wholly Marxist; those that do are now avuncular figures guiding younger non-Marxist scholars with revived interests in accentuated social inequalities. Past barricades have liquefied in the same way as other certainties like employment or welfare.

Today those practicising “theory,” as it has come to be called, serve up a bricolage or melange of ideas rather than isms. What’s more, such ideas are exhibited so ecumenically that liberals should be proud to have ended history, so to speak, in the academy.

This post-theory moment is best characterised by “intersectionality”: an approach that retains vestiges of theory past by incorporating the classic social theory triptych – race, gender, class – in different permutations. Marx remains relevant but is by no means dominant. Culture is central but that doesn’t mean everything is relative.

One important direction at this intersection is queer theory. Its advocates – like Rosemary Hennessey, Judith Butler, and Jose Esteban Muñoz – bring attention to injustices against the LGBTQI people under capitalism by critiquing of social norms – not just based on sexuality – and offer ways of rethinking social life with a view to recognising, accepting, and celebrating difference.

All of this destabilising inclusivity runs counter to Bernardi’s agenda. Were Bernardi to flick through a copy of Butler’s Gender Trouble, perhaps as he sips a latte, he would certainly find fault. But this is precisely because he embodies the chief target of these theories: the normativity of privilege, whiteness, manhood, and heterosexuality.

The degree to which this social theory influences the policies of the Safe Schools Coalition is difficult to ascertain. Much like the brouhaha over the Australian Curriculum’s historical biases and oversights, any Coalition investigation into this “other” Coalition is likely to result in a predictable response – an agreement that the organization should support LGBTQI people in schools alongside some gesturing about not pushing a queer agenda.

In other words, this issue has come to the fore not so much to stop LGBTQI kids getting attacked at school so much as propping up the collapse of the Turnbull government’s popular support.

So if Bernardi’s description of social theory is out-of-date, his political acumen remains crisp.

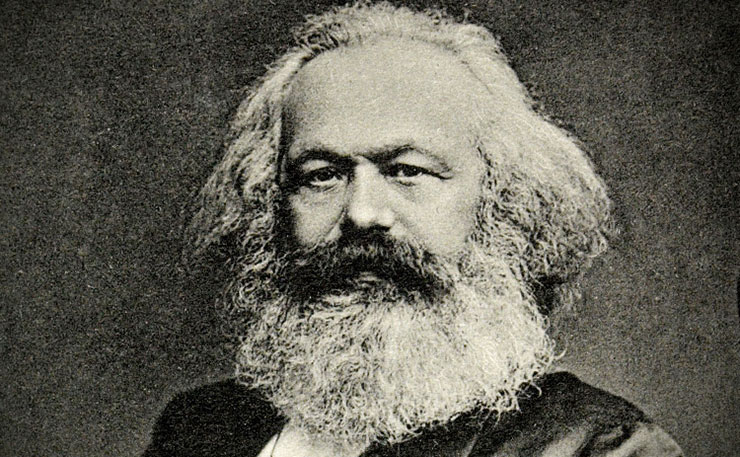

There is, however, an irony in this situation: Bernardi’s “conservative revolution” exemplifies what the Italian (cultural) Marxist Antonio Gramsci called a “war of position.”

Gramsci, arguably “theory’s” main progenitor, suggested that modern social life was chiefly an ideological struggle between opposing vested interests. This view is easily transferable to the debate over improved gay rights in Australia: a majority supporting them and a minority against the idea.

The intransigent minority recognizes that the only way to defend their backfoot position is through pre-emptive ideological attacks in civil society.

Bernardi’s masterstroke is to take aim at a site of social vulnerability and potential – school children – by offering performative sound-bites. They signal more reports in a cultural war that conservatives have so adeptly engaged in the face of social progressivism and economic liberalisation.

But playing this cultural card may not come up trumps with both the party and with voters.

For the party room, the move is a call to arms: Turnbull is still on probation and this matter is designed to test his skills as leader. The Prime Minister’s Pavlovian reaction to Bernardi’s shrill is indicative of his precarity. It is a response unnecessary to his progressive talk about the new economy, technology, and innovation.

For the general public, the gays-under-the-bed line is a risky move. “Marxist cultural relativism” may translate in some electoral battlefields as “leftist, brown, atheists (who are probably lesbians)”. It might work in the same way as highlighting subtle concerns about queue-jumping asylum seekers or Chinese property owners.

But attacking the Safe Schools Coalition appears as bigotry or a flailing counterpunch to the end of the school chaplaincy program. The populous has little time for beat ups. Its widespread support for LGBTQI rights – especially the very un-radical same-sex marriage fait accompli – is complemented by a backdrop that includes commissioned justice for physical and sexual abuse victims, intolerance towards bullying wherever manifest, and prominent mental health discussions across social groupings.

Still, Bernardi’s pontificating is a timeless political strategy. He may not know his Marxist cultural relativists from his post-structuralist feminists, but he certainly understands that when power-holding interests are under threat it’s wise for them to take aim at the group seeking recognition and empathy from those used to vilifying them.

It is, as both he and Gramsci would say, although with different intent, a matter of “common sense.”

Eve Sedgwick, a queer theorist, put it another way when she explained that how people are labelled is less important than how those labels are mobilised – either positively or negatively – in our daily interactions.

“People are different from each other,” she said more than 25 years ago, “it is astonishing how few respectable conceptual tools we have for dealing with this self-evident fact.”

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.