When Fremantle MP Melissa Parke steps down at the next election she won’t be remembered as a Labor great who rose to the party’s highest offices and stamped her name on its history. But at a time when politics faces accusations of a conviction deficit, and the ALP struggles to forge an identity deeper than that required by the latest focus group, her career demands closer inspection. In this special extended feature, Max Chalmers profiles a Labor renegade.

In late 2014, former Israeli soldier Marcelo Svirsky walked 300km from Sydney to Canberra and presented a petition to the Federal Parliament. It urged Australia to back BDS, the ‘boycott, divestment, and sanctions’ campaign which replicates tactics used against Apartheid South Africa, turning them on the state of Israel.

On the day he arrived Svirsky had the petition tabled, somewhat surprisingly, by a Labor MP, the Member for Fremantle, Melissa Parke.

In her almost nine years in Canberra, the former UN lawyer had come to play the role of Labor’s public dissident, voicing opposition to major policy positions within Caucus and going public with her arguments when they didn’t register inside the tent.

On a number of occasions, as with the day she rose to speak on Marcelo Svirksy’s petition, Parke used her parliamentary platform to address an audience beyond the halls of influence and power that wind through the building.

Where Labor aligned itself with the Coalition for the sake of political expediency – particularly in the areas of national security and refugee policy – Parke broke ranks, chastising the Coalition for reckless lawmaking and implicitly rebuking those on her own side of the aisle.

Parke mastered the thankless art of the political soliloquy.

By consistently advocating in this manner Parke’s career opens itself to two intriguing questions. Firstly, was this MP the real deal, the conviction politician we’re so often told is absent from the modern parliament? And secondly, if so, are figures who push from within Labor’s left destined to do more harm than good for the causes they so passionately espouse?

To answer those questions, we need to return to Marcelo Svirksy while also looking further abroad; to the streets of Gaza City; to a bombed-out UN compound in Baghdad; and to the Labor Caucus meetings that moved Melissa Parke to go it alone.

The tabling of a Parliamentary petition is not what you would usually describe as an exciting affair, but the day Parke presented the BDS signatures there was a nervous energy to her remarks.

“What I am [going]to say today will likely not be popular in this place or indeed in the wider community,” she said.

“However, there comes a time when the injustices have so mounted up that plain speaking becomes a duty.”

In the rapid-fire comments that followed, Parke accused Israel of “persisting in apartheid and oppressive actions” and goaded MPs to sanction states or companies involved in “the perpetuation of discriminatory Israeli policies”. She argued in favour of non-violent protest, took aim at “myths” about BDS, and said it was not anti-Semitic to protest injustice.

Despite being delivered to a near empty chamber, Parkes’ remarks were punctuated by outraged interjections.

For a Labor MP, indeed for anyone in that chamber, Parke’s rhetoric was radical. She was putting phrases into Hansard that don’t often appear in relation to a state Australia considers an ally. This was not the tempered language critics of Israel in mainstream Australian political life generally employ: it was ardent, passionate, and unflinching.

When I visit Parke in her parliamentary office a year on from Svirsky’s trek, it becomes clear that despite being outspoken, the MP chooses her words carefully. Her demeanour is steady and deliberate, as well as friendly and polite – descriptors used by those who have worked with her, and against her.

Parke doesn’t explicitly state support for the BDS campaign in its entirety, though she says she believes it is working, and notes sanctions are used routinely by states like Australia, the US, and Israel itself.

The closest Parke comes to a total endorsement is a rhetorical question: “Why would we not do it in the case of Israel, when they are so flagrantly in breach of so much of international law?”

There’s a pragmatic answer to that. The issue of BDS in Australia, and of the Israel/Palestine conflict generally, remains politically unrewarding. Support begets accusations of anti-Semitism and, as the Greens have learnt, dogged attacks from the conservative press.

If you’re unlucky you might even end up in court. Meanwhile, most Australians couldn’t tell you the first thing about the ageing conflict. The repercussions for pushing it onto the public consciousness are severe, and the political payoffs somewhere between questionable and non-existent.

In that climate, it makes more sense to flip Parke’s question on its head: why would you try to do it?

Parke’s response to this draws on international law and realpolitik – solving the conflict will take valuable propaganda away from the likes of Islamic State, she says. But her decision to advocate so strongly taps a deeper, more personal source as well.

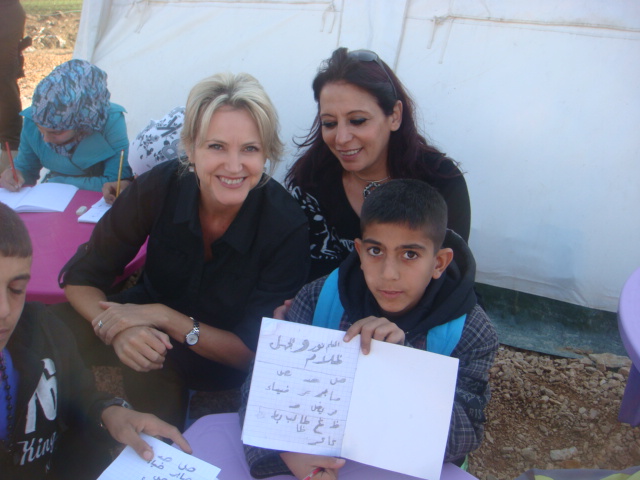

As the Second Intifada raged – a bloodier cousin to the first Palestinian mass rising of the late 1980s –Parke was in Gaza. Working as a Legal Officer for a UN refugee agency, she liaised with the Palestinian Authority and the Israeli Defence Force to get staff and humanitarian supplies through checkpoints. From her apartment in Gaza City she could look out on the Mediterranean Sea – a “fantastic view” – as well as peer into Yasser Arafat’s compound and a refugee camp.

At the time, Israel was deploying what Parke describes as “a sort of shock and awe bombing campaign”. She says 36 bombs were dropped during her first night in Gaza City, shaking her building and its surrounds. She lay awake.

Then Israel started targeting leaders of Hamas – too bad if you’re the one who gets stuck in traffic behind them when the IDF locks on.

“You could be driving behind the car targeted with Hamas in it and you’re gone as well,” Parke say. She was scared, and her fears were soon vindicated.

The same year as Parke arrived in Gaza, a place she stayed for two and a half years, fellow UN worker Iain Hook was shot in the back by an Israeli sniper from a nearby building. Hook was in the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank but was inside a UN compound at the time he was shot. He’d been there to help rebuild homes.

Israel contests the exact details of the killing, but those like Parke believe the shooter must have known who they were about to slay.

Despite some outrage, and conciliatory calls from Israel’s then foreign minister Benjamin Netanyahu to the English government, a UN resolution condemning the murder was vetoed by the United States.

The killing of Hook and lack of international response outraged Parke, and she carries the injustice of it with her still. So too the many others she witnessed directly in the shelled and re-shelled streets of Gaza City.

“I didn’t go there with a pre-conceived view,” Parke insists. “I obviously had read about the situation. But it’s not until you’re there on the ground that you come to appreciate the absolute imbalance of power. You’re talking about the fourth largest military power in the world with the latest technology and with an army, navy, air force, versus an occupied people – an impoverished, occupied people.”

These experiences soaked deep into Parke. When I try to move the interview on at one point, she pulls us back to Palestine. This is what she wants to talk about and part of the reason she came to parliament: to grab the megaphone, and to use it.

Before entering Parliament, Parke worked as community lawyer in south-west Western Australia, near where her family farmed and exported Granny Smith apples. She joined Labor in 1995 and took an unsuccessful shot at the state seat of Mitchell in 1996.

Hansonism had swept the country and many of those whose doors Parke knocked on counselled her to take a leaf out of the xenophobic Queenslander’s book.

After her defeat – “a relief” – she lectured in law at Murdoch University, then took a job as a lawyer with the UN. Once at home in the Bunbury Community Legal Centre she now found herself in Kosovo, Gaza, Lebanon, and New York.

By the time Parke received an “out of the blue” email from sitting member Carmen Lawrence, encouraging her to return from overseas to contest the federal seat of Fremantle at the 2007 election, she was working in a Beirut office with Amal Alamuddin (the woman who later married George Clooney).

Lawrence, who became the nation’s first female premier before moving into the federal arena, describes Parke as a “country girl”. Her and others were impressed by Parke during her first missive into politics, and didn’t think the young lawyer had the kind of “remote” or “abstract” feel those involved in international organisations sometimes give off.

Speaking by phone from her University of Western Australia office, Lawrence agrees Parke’s road to federal Parliament wasn’t typical.

“It wasn’t through that elaborate factional dealing and brawling process; that unfortunate incest in the Labor Party – and the Liberal Party for that matter – and a lot of student politics,” she says.

Lawrence sees both a benefit and a disadvantage to this lineage. On one hand, Parke wasn’t an “insider-insider” who had worked with party players from day one, and came without a pre-existing network of supporters and loyalists. On the other hand, that would leave her under fewer restraints, freeing her to inject a fresh voice into the mix.

Parke jumped at the chance.

“I got this email and went ‘Oh my god’,” she recalls. “Amal was like ‘what what, tell me, what is it?’ And so I told her and we were both pretty amazed. Carmen said I should think about it for a while so I did. And eventually I came back to her and said ‘Yes, I’d love to do it’.”

This time the political winds had changed. John Howard would be defeated at the election by a Labor government promising action on climate change, a more humane refugee policy, and national infrastructure and education programs. It was the right moment for Parke’s entry into national life.

In her first remarks to Parliament – on a day that saw Greg Combet, Maxine McKew, and Bill Shorten also make theirs – Parke described politics not as the art of the possible, but as an act of war. It was a figurative sentiment, but it drew on another moment of very real conflict.

“In life we tend to remember moments rather than hours or days or years,” the new member for Fremantle observed.

“I will surely remember this one, as I also remember the moment when I learned that my friend Jean-Sélim Kanaan, one of the UN’s best and brightest, with whom I had worked in Kosovo, was killed in the bombing of the UN headquarters at the Canal Hotel in Baghdad on 19 August, 2003.”

Posthumously awarded France’s Legion of Honour, the 33-year-old had perished in an attack that left the UN’s top representative in Iraq, and 20 others, dead. His son, who survived him, was three weeks old at the time. A short time before his murder, Jean-Sélim Kanaan published a book titled Ma guerre à l’indifférence – ‘My war against indifference’.

Parke didn’t just pay tribute to Kanaan in that opening speech. She also borrowed the name of his book to help develop the key theme of the address.

“I hope that my work in this place on behalf of the people of Fremantle can be part of an ongoing cooperative effort towards more such victories in the war against indifference,” she concluded.

Years later, at the other end of that battle, she still believes the maxim.

“Indifference: that is the biggest challenge,” Parke says. “People are so busy, getting busier and busier it seems every day. How do you get people to stop and actually focus on something long enough to have a position on it?”

Her advocacy on the Trans-Pacific Partnership has been a case in point: a technical and unsexy policy area which she has long railed against, trying to thrash the debate into mainstream consciousness.

As we discuss her campaigning on the issue, Parke comes out with a surprising self-characterisation.

“I see myself as an advocate primarily… I certainly don’t see myself as a politician,” she says.

It’s a strange thing to hear from an MP while sitting in their parliamentary office – it strikes me as the kind of place you might well expect to find one. But at multiple points in our conversation Parke insists that’s not her.

“If I was a politician, I wouldn’t be a very good one,” she continues, arguing she hasn’t been enough “into the politics of things” to work out how the horse-trading and deal making really works.

Parke sometimes plays up her own political naivety, and it’s not always clear if she’s being self-deprecating, or proud, or both. In one instance, she tells me about a meeting in which she encouraged a left-wing union to stop putting energy into combatting another left-wing union, and focus instead on the Liberal state government.

“They just looked at me like I was just some little country bumpkin who’d crawled out from under a rock in a pitying sort of way: ‘oh, you’re so naïve’. But I don’t think I’ve ever lost that sense that we should be looking at the bigger picture here. That’s how I try to approach everything that I do.”

It’s this approach that makes Parke an interesting figure of comparison to other MPs on the left of the party, particularly someone like Tanya Plibersek.

Both Parke and Plibersek secured progressive inner-city seats and have an affinity for development and international affairs. Both are used as counter-examples by party faithful disillusioned with the middling leadership of Bill Shorten. Both have a powerful charisma and independent streak. But only one has played the disciplined insider game: Plibersek now finds herself on the ladder’s penultimate rung.

Yet as Michael Brull has noted, Tanya Plibersek underwent a transformation over the period of her ascent, especially in regards to international affairs.

In earlier times, Plibersek decried Ariel Sharon as a war criminal and blasted the US, but by the time he died in 2014, she was thanking the former Israeli leader for his “courageous stand” for peace.

At Labor’s 2015 conference, a motion trying to stop the party supporting turn-backs of boats carrying asylum seekers was defeated, with the left drawing small concessions including more funding for the UNHCR and an increased humanitarian intake in return. Plibersek described it as a “humane, compassionate and sensible” outcome saying she “could not be prouder”.

In her Canberra office, Parke calls the turn-back policy an “absolute disgrace”.

While Brull’s analysis concludes “at least Plibersek’s journey will provide a salutary lesson about the ALP, by showing her grim but predictable slide from idealistic ALP firebrand, to cynical imperialist apparatchik”, Plibersek doesn’t see the cooling of her rhetoric in quite the same light.

As Labor bent ever further backwards to keep itself aligned with the Coalition on all things security in 2014, Plibersek was profiled by The Monthly. She defended her party’s support for laws that would jail Australian journalists, scoop-up the entire country’s metadata, and greatly increase the powers of security agencies. She made no apologies.

“Look, I can be fierce, sometimes. The things that we argue about in [parliament]matter. There are times in politics when you think, ‘Wouldn’t it be good to do the grand gesture?’,” she told The Monthly. “But it’s almost always a mistake because… you wear the consequences of a defeat.”

To put it another way, she’s chosen her battles. No big speeches on Palestine. No tears over refugees. You do your lobbying out of sight, if you do it at all, and you take the prizes as they’re handed to you. You might move the party on major policy debates in the long run; you certainly won’t inspire the nation in the meantime.

When I first read that Plibersek quote, I read it as a criticism of people like Parke. Parke says the playing-from-inside point of view is valid, and that there are different roles for different people in the party. She doesn’t see herself as a moral grandstander. Despite the cordiality, her response also comes across as a polite rebuke of her not-quite-rival.

“I’ll leave it to the politicians to finesse how a deal could be done with the other side to achieve something,” Parke says. “But I would prefer to start by saying ‘what’s the right thing to do’ and we can look at how we would achieve that rather than immediately accepting upfront the compromise position without even pushing for the right position.”

Politics may be war, but Parke still describes it as hinging on a simple moral calculus.

It should be noted that whatever her colleagues think of Parke’s parliamentary outbursts, the sources I spoke to in the world of refugee politics certainly didn’t see her work as self-serving.

According to human rights lawyer Julian Burnside she’ll be a big loss.

“I think she’s been fantastic,” he says. “In my view she’s been one of the very few Federal MPs who has actually been saying worthwhile things about refugees.”

One insider in a major refugee organisation described Parke as “absolutely genuine”.

“Melissa is a legend,” they told me. “Anytime you need anyone in parliament to do anything on refugee stuff you go to her.” (Parke recently presented another petition to parliament, this time on behalf of refugee advocate Dr Diana Cousens, calling for the witness to Reza Barati’s death to be brought back to Australia.)

Pamela Curr, a prominent member of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre and the most critical of Labor of the advocates I talked to, also had kind things to say, despite noting with despair that Parke and her ilk were constrained by their party.

While hesitant to criticise individuals, Parke is clear in her critique of Labor’s internal machinery. She blames the surveillance and security capitulation on a top-down flow-on effect.

Tanya Plibersek, Penny Wong, and Stephen Conroy were all members of the bipartisan Intelligence and Security Committee that approved security laws threatening journalists with lengthy jail stints for exposing special operations – laws that the government has since agreed to amend after a scathing report by the Independent National Security Legislation Monitor.

According to Parke, the presence of shadow Cabinet members on the Parliamentary Committee examining the laws led to an overlap, effectively causing the Shadow Cabinet to bind to the compromises struck with the Coalition. This decision then flowed down to the Shadow Ministry.

By the time the matter actually came to caucus it was a forgone conclusion. The party leadership had effectively killed off the chance for robust internal debate.

As someone strongly in favour of civil liberties and deeply opposed to overriding executive controls – both of the government over the parliament, and the party executive over its members – Parke was left frustrated by Labor’s acquiescence and faulty process.

“We were told ‘This is the position the leadership has taken, and they’re on the Intelligence Committee, and they’ve negotiated this with the government. No correspondence will be entered into: it’s a done deal’,” she recounts.

Despite her resistance and criticisms, Parke did manage to rise sufficiently within the party to briefly score a ministerial post, becoming the Minister for International Development months out from the 2013 election. After Labor was cleared out of government, another woman on the party’s left wanted the role, and I ask Parke if she had been interested in retaining it in opposition.

“Oh, I would have loved to,” she says “But that was a role that Tanya was very interested in as well and it fit in well with her foreign affairs portfolio.”

Plibersek now holds the position.

Not long after Parke’s arrival in Canberra the political winds changed again. Labor shelved its plans for an Emissions Trading Scheme and Kevin Rudd was deposed as leader. Julia Gillard later cut higher education funding, albeit as a way of freeing resources for the Gonski plan, reduced payments to single mothers, and oversaw an increasingly punitive refugee policy that climaxed with (the returned) Rudd’s new Pacific Solution.

At her high point, as the Minister for International Development, Parke watched her portfolio fall victim to the ‘budget emergency’. She says Treasury and Finance were to blame.

“That was fairly devastating actually. To be in a position of Minister very briefly, for foreign aid, and having to defend the budget against incursions on it – and losing the battle.”

A losing battle. It’s a phrase Parke mustn’t use lightly: the one both critics and fans who spoke to New Matilda referenced often when describing her time as an MP. For all her gall, she leaves politics at a time when Labor’s refugee policy is the most cruel and punitive it has ever been.

In defence of her own approach Parke points to some of Labor’s achievements in government as well as internal shifts on policy. Animal welfare, another area of unabated passion, has moved along, and Parke was particularly pleased by Labor’s introduction of a network of marine reserves while still in government.

One of her more prominent constituents, writer Tim Winton, travelled to Canberra to help drum up support for the proposal in 2012. The National Disability Insurance Scheme is in place too and Labor funded the now threatened Gonski plan. Modest public whistleblower laws were enacted. For all the infighting, the Rudd/Gillard years did see some progressive reforms bloom.

Other more ambitious interests of Parke’s, for instance forcing the government of the day to seek parliamentary approval before declaring war, have gone nowhere.

It’s hard to pinpoint the exact impact of any MP and Parke is keen to note that nothing in Canberra happens without a wide range of collaboration, among MPs, staff, researchers in the parliamentary library, community groups and academics. But she does see her own fingerprints on some triumphs, for instance Julia Gillard’s backdown over voting no to Palestinian observer status at the United Nations.

If you accept that Parke has played a role in these changes, her time in parliament throws up a more difficult question, one relevant to any MP on Labor’s left who publicly dissents from the party line.

A senior member of the Greens – who was otherwise full of praise for Parke – proffered the following: what if her outspokenness actually helps reinforce the status quo she is trying to resist? What if Melissa Parke’s voice of conscience only allows Labor to sin further?

Progressive voters get the ‘Parkes’ and the ‘Anna Burkes’ as their champions, swing voters harangued into a terror over boat people get their hardline policies, Labor gets to have its soul and eat it too. The party keeps left-wing voters in the tent while solidifying around a more conservative platform. Everyone wins – except those who find themselves in a detention centre somewhere in the Pacific.

There seems to be some acknowledgment of the underlying rationale of this argument by those sympathetic to Parke. Carmen Lawrence, for one, doesn’t buy it, but says MPs like Parke do enable parts of the electorate concerned about civil liberties and human rights “to hold their noses and continue to vote Labor”. This, she says, has prevented what would otherwise be “an even bigger flood” to the Greens.

Parke seems genuinely surprised by the line of reasoning.

“I’m certainly not doing what I do for some broader political gain for the Labor Party as a cynical exercise in keeping people in the left of the Party rather than going to the Greens or independents,” she says. “That would just be – that’s the opposite of everything I believe in. I don’t think anyone who knows me would think I was doing it [for that reason].”

Parke’s stance on the Greens aligns with this self-assessment. She says she has no “deep criticisms” of the party. It’s a somewhat more polite response than that of other Labor leftists like Anthony Albanese, let alone those in the right of the party.

“Look, I know this is just anathema to so many people in Labor but I don’t see [the Greens]as the evil enemy,” Parke says. In fact, she sees much common ground between the two. She even sees the prospect of a new coalition emerging.

“I think in the future, in the same way that the Liberal Party relies… on the Nationals to form a Coalition, that’s the kind of thinking that we might need to go to in the future because we may not, in our own right, have the numbers. Particularly if we are not pursuing a very progressive agenda in some areas.”

Given those sentiments, it’s tempting to ask why Parke never jumped ship. Why not go with the Greens? She frames her response around loyalty rather than power. It was Lawrence who emailed her in Beirut and the party that helped her campaign and win. She’s grateful for what they’ve done for her. Plus, she’s drawn to Labor’s history and points to Doc Evatt and Jessie Street – the lone female presence in Australia’s key contingent at the birth of the United Nations – as sources of political inspiration.

Despite being told by an online political compass that the sum of her beliefs should point her to voting Greens, Parke says she has always cast her ballot for the ALP.

On the eve of her retirement, Parke hasn’t lost the Labor faith. When I asked her in late 2015 whether her peers deserved to return to government she gave a refreshingly honest answer: “I think we still have more work to do”.

By the time we speak again in February 2016, she thinks things have changed. Labor has doubled down on Gonski, vowed to go after negative gearing and superannuation concessions for the wealthy, and is starting to take a more substantial policy debate to Malcolm Turnbull.

Parke also thinks Labor has learnt a lesson from the security bipartisanship, and that there has been an “auto-correction”.

She backs Bill Shorten for PM, impressed by the way he has unified the recently fractured party. There’s a slight qualification, though.

“I hope that would be a Bill Shorten who is unashamedly putting forward Labor values based on human rights and fairness. I know that he certainly would be on other matters of intrinsic importance to the Labor Party; public health and education; fair and safe working conditions; public transport; infrastructure; and protecting the environment, but I am concerned about the issue of refugees, the position that’s been taken by the leadership,” she says.

Early this week Shorten shot back at Cory Bernardi in the kind of off-the-cuff remark Labor’s true friends have been waiting to hear for some time. The moment was brief, small even, but it provided a rousing image of defiant opposition. The darkest elements of Australia’s conservative political movement had made themselves noisily apparent in the nation’s capital, but they hadn’t gotten away scot-free.

For Shorten, the task ahead involves convincing Australians he stands for something beyond himself, breaking down the grey portrait of a leader at the mercy of focus groups and faceless men.

As the party tries to rebuild itself into a coherent progressive project that can channel changes in the community into something bigger, Melissa Parke’s war on indifference reaches its ceasefire.

If her party fails to find room for others like her in the future they’ll be losing more than once untouchable seats to the Greens.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.